Breakfast Blueprint

Breakfast After the Bell Programs Support Learning

“Every student in my class looks forward to eating breakfast in the classroom. Some students do not have time or food to eat before they get to school. Students were complaining of stomachaches, but now with breakfast in the classroom, there is less complaining.” —Elementary school teacher, California

The American Federation for Teachers (AFT) and the Food Research & Action Center (FRAC) are committed to strategic partnerships at the school, district, state and national levels to advance children’s health and well-being. We especially value collaborative approaches to address children’s food security. One way the AFT and FRAC work together is to ensure that all children, especially those struggling with hunger, have access to healthy school meal programs.

Thanks to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, federally funded school breakfasts and lunches are more nutritious than ever. The law ushered in requirements that school meals include more fruits and vegetables, more whole grains, less sodium, no trans fats, and limits on saturated fat and calories. Nearly all of the nation’s schools are meeting these new, health-based guidelines.

Research shows that hungry students are at a significant disadvantage in the classroom, while students who eat breakfast at school are more attentive, less likely to act out, less prone to becoming overweight or obese, and better academic performers. As documented in FRAC’s “School Breakfast Scorecard” and addressed in the AFT’s resolution “Healthy and Hunger-Free Schools,” many children miss breakfast when it is served before school starts. According to FRAC’s “School Breakfast Scorecard,” for every 100 low-income students who participate in school lunch programs, only 56 participate in school breakfast.

The operation and logistics of school breakfast programs significantly impact their reach. Timing of meal service, hectic morning schedules, late bus arrivals, students’ desire to socialize with friends, the financial burden of co-payments for families who qualify for reduced-price school meals and the social stigma associated with participation can hinder students from eating school breakfast. To address these challenges, schools may consider a variety of strategies, including morning schedule adjustments, increased collaboration with families or breakfast after the bell programs.

The “Breakfast Blueprint” is a guide focused on breakfast after the bell programs—such as breakfast in the classroom, “grab and go” breakfast and second chance breakfast—because they are increasingly popular, are well-researched and have successfully helped schools and districts improve students’ access to nutritious foods. These innovative models shift breakfast service from before the school bell to after, making morning meals available to more students. Combined with providing breakfast at no cost to all students regardless of income, breakfast after the bell eliminates stigma and increases convenience for students.

What does the research say about ...

Hunger’s impact on learning in the classroom?

Children who are hungry are more likely to:

- Be hyperactive, absent or tardy.[1]

- Experience behavioral, emotional and academic problems.[2]

- Repeat a grade and have lower math scores.[3]

The educational and health benefits of school breakfast?

Children who eat school breakfast:

- Demonstrate improved concentration, alertness, comprehension, memory and learning.[4], [5], [6]

- Show improved attendance, behavior and standardized achievement test scores.[7], [8]

- Are more likely to consume diets that meet or exceed standards for important vitamins and minerals.2, 3, [9]

[1] Murphy JM, Wehler CA, Pagano ME, Little M, Kleinman RF, Jellinek MS. (1998) “Relationship Between Hunger and Psychosocial Functioning in Low-Income American Children.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37:163-170.

[2] Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Little M, Pagano M, Wehler CA, Regal K, Jellinek MS. (1998) “Hunger in Children in the United States: Potential Behavioral and Emotional Correlates.” Pediatrics, 101(1):E3.

[3] Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. (2001) “Food Insufficiency and American School-Aged Children’s Cognitive, Academic and Psychosocial Development.” Pediatrics, 108(1):44-53.

[4] Grantham-McGregor S, Chang S, Walker S. (1998) “Evaluation of School Feeding Programs: Some Jamaican Examples.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(4):785S-789S.

[5] Brown JL, Beardslee WH, Prothrow-Stith D. (2008) “Impact of School Breakfast on Children’s Health and Learning.” Sodexo Foundation.

[6] Morris CT, Courtney A, Bryant CA, McDermott RJ. (2010) “Grab ‘N’ Go Breakfast at School: Observation from a Pilot Program.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(3):208-209

[7] Murphy JM. (2007) “Breakfast and Learning: An Updated Review.” Journal of Current Nutrition and Food Science, 3(1):3-36.

[8] Basch, CE. (2011) “Breakfast and the Achievement Gap Among Urban Minority Youth.” Journal of School Health, 81 (10):635-640.

[9] Pollitt E, Cueto S, Jacoby ER. (1998) “Fasting and Cognition in Well- and Undernourished Schoolchildren: A Review of Three Experimental Studies.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(4):779S-784S.

“Breakfast in the classroom can be done properly when all structures and routines are put in order by the school.”

—Elementary school teaching methods coach, Missouri

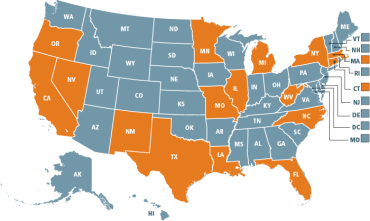

Given the critical role school breakfast plays in children’s well-being and overall academic performance, the AFT and FRAC conducted research to uncover best practices and strategies for successfully operating a breakfast after the bell program. Nearly 600 teachers, paraprofessionals, food service staff, school health professionals and custodians from California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Texas and West Virginia shared their perspectives in surveys, focus groups and structured interviews.

Orange denotes a state engaged for this report.

Several common themes emerged:

- School personnel value the benefits of healthy breakfast for their students, especially the opportunity to promote social relationships and serve vulnerable children. They want students to have the healthiest meals possible, and many would like to increase the use of fresh, local, scratch-cooked foods.

- Top-down implementation and non-inclusive planning frustrate faculty and staff. Further, these approaches can undermine program sustainability. School personnel wish to be included in planning and improvement processes.

- Many educators are eager to share their ideas on how schools can improve students’ access to nutritious foods. For example, they advocate for consistent use of simple packaging to better serve students with disabilities and culturally familiar items to boost student satisfaction among ethnically diverse populations.

- At times, the logistics of breakfast after the bell programs do not fully account for the time required of custodial, instructional and food service staff to complete all their responsibilities. For teachers, there is often a tension between the time needed to facilitate breakfast service and the expectation to teach “bell to bell.” Educators call on administrators to provide more training and to be more explicitly supportive of the new routines and activities that are being integrated into morning schedules to ensure a smooth start to the day.

- For successful implementation, many programs need resources like cleaning supplies and appropriate equipment to store, transport and dispose of foods.

Based on this research, the AFT and FRAC developed the “Breakfast Blueprint.” This series offers strategies on how to plan, execute and improve breakfast after the bell programs. We hope the content spurs constructive dialogue among typical decision makers, including food service directors, union presidents and school superintendents, as well as frontline staff who implement the programs, including teachers, paraprofessionals, custodians and cafeteria workers.

Set Up Your Program for Success

“The committee supporting the new breakfast plan should include a staff person from each area of the school to participate in implementing the new plan and making decisions about changes to breakfast and instructional time.” —Elementary school paraprofessional, West Virginia

When your district establishes a new breakfast after the bell program, it may be the first time that diverse staff work together on a shared vision. They likely will bring different priorities, challenges and training backgrounds. Successful breakfast after the bell programs create open lines of communication across traditional silos, while providing opportunities for all stakeholders to give feedback on ways to improve logistics.

Include diverse voices

Many of the survey respondents expressed a willingness to contribute time and ideas to the successful implementation of new breakfast after the bell programs, yet nearly half whose schools had adopted a new breakfast service model reported being “unsure” of the stakeholders who had a chance to participate in planning, while another 1 in 5 reported that only administrators contributed. Empowering an inclusive, district leadership team to oversee planning, implementation and evaluation builds strong after the bell programs. That team should consist of a diverse group of voices who will be implementing and impacted by the program.

- School leaders, such as school board members, superintendents and principals, are instrumental gatekeepers who can champion the program among families and the community.

- The district’s food service director oversees the development and execution of breakfast after the bell programs and must balance meeting the diverse needs of schools and staff with state and federal requirements.

- Labor unions represent the collective voices of staff—including bus drivers, custodians, food service workers, office staff, paraprofessionals and teachers—whose roles and responsibilities within the district can inform thoughtful planning and implementation.

- Anti-hunger advocates are often skilled at sharing lessons from other districts; they also may have relationships with funders.

- Students and families are effectively “customers” whose input can ensure the success of innovative menu items, meal preparation and more.

Empower the team

While the food service director oversees a smooth transition and a sustainable program adoption, the entire leadership team should be equipped with the time, space, leadership and other resources to provide robust support, feedback and engagement. Having team members visit a school with a successful breakfast after the bell program may help them build shared knowledge and learn more about strategies to achieve the district’s goals. As the program begins, the team will need to form a coherent district plan that may require flexibility for the unique needs of various schools. As schools approach their launch date(s), the team should conduct training and ease schools into new routines. Finally, as the new program takes root, the team should determine which stakeholders are responsible for evaluating the program and adopt a structured approach to reviewing evaluation data to make improvements and address challenges quickly.

Throughout the life of the breakfast after the bell program, the team should work with the food service director to support and guide program improvements. Furthermore, at each step, the team will benefit from regular communication with broader stakeholder groups, both to collect authentic feedback and to report out the work of the team.

A labor-management “think tank”

New York City schools began to roll out a universal breakfast in the classroom program in the 2015-16 school year. Several logistical challenges emerged. For example, school personnel were concerned about eliminating hot breakfast service. Several of the city’s unions quickly realized the need to connect with frustrated members. The United Federation of Teachers developed an online assistance form that enables members to request help and intervention for school-level issues. Additionally, the union website lists a health and safety staff contact who is assigned to directly field concerns.

The unions also brought their concerns to the deputy chancellor, who convened a “think tank” with representatives of food service staff, custodians, school aides, teachers, paraprofessionals, principals and other administrators. Over the last year, the group has met to review feedback from different stakeholders and troubleshoot together. One UFT vice president reports that strengths of the group include “being able to voice concerns in a timely fashion” and “having the group think through it at once.” To date, the group has:

- Created a hybrid service model that blends cafeteria service for students arriving early and breakfast in the classroom for those who arrive close to the start of class;

- Coordinated adult assistance for opening prepackaged items for young students to limit spills;

- Developed a food service team to verify that any school interested in serving hot breakfast has appropriate equipment; and

- Established a protocol to conduct school-based investigations of challenges within 24 hours of a report being generated, such as through the UFT’s online form.

The New York City Department of Education also created a 33-page guide on incorporating nutrition education into elementary school lessons in the morning and developed a PowerPoint to guide training sessions.

Plan for a Successful Launch

“Start slow. Do a lot of preplanning so change doesn’t come as a shock. Some may feel like, ‘I really do want students to have breakfast, but I don’t know what was wrong with the old system.’ There has to be some explanation about why you’re changing to this new model and some recourse if it’s not working. How can folks share their challenges?” —Union vice president for elementary schools, New York

Implementing a new breakfast service model alters daily operations and routines for many staff, including custodians, food service workers and instructional personnel. Without clear guidance on new expectations and routines, many staff can become frustrated and dissatisfied. Successful breakfast after the bell programs facilitate smooth transitions by communicating the district’s intentions along with broad guidelines to participating schools.

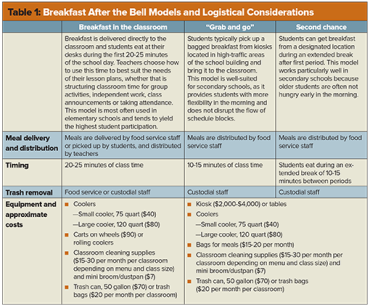

First, choose a service model or a combination of models. (See Table 1 below for an overview of the breakfast in the classroom, “grab and go” and second chance breakfast models.)

Develop a flexible district plan

While weighing the benefits of each, consider the pros and cons of maintaining some breakfast service in the cafeteria. Then, draft an implementation plan that broadly addresses the following logistics:

Timing: Many districts phase transitions, such as by starting with elementary schools or working first with buildings where the schedule easily accommodates second chance breakfast. Consider:

- How will this impact the school day and schedules?

- Can homeroom, advisory periods or other regular elements of the schedule be leveraged?

- Will bus transportation be impacted?

- When will the program launch?

Equipment and resources: Breakfast after the bell programs usually increase the number of spaces where food is served. Many aspects of the school building’s layout can impact breakfast distribution, including student traffic, cafeteria location, number of floors, elevator accessibility and size, as well as classroom spacing. Assess the need for additional kitchen storage space or additional tables, coolers or kiosks for food distribution. Maintain high safety and hygiene standards for all spaces where food is served by regularly distributing cleaning supplies. Consider:

- Are new equipment or supplies needed?

- How and when will teachers and paraprofessionals receive classroom cleaning supplies?

- How will staff members communicate the need for assistance with cleaning up larger spills?

Staffing: Collaborate closely with staff unions to examine how scheduling may change as student demand increases with a breakfast after the bell program. Consider:

- Which staff members will distribute food to the classrooms/kiosks and at what time(s)?

- Which staff members will pick up trash and at what time(s)?

- How many food service personnel are needed and at what time(s)?

- How many custodians are needed and at what time(s)?

Training: Breakfast after the bell programs often require diverse staff to work in close concert. It is important that all stakeholders understand the professional guidelines and expectations of their colleagues, such as the role of standardized testing in teachers’ evaluation, the federal requirements for meal participation tracking for food service staff, and the safety standards that guide custodians. Consider:

- Who will train teachers, paraprofessionals, custodians and food service personnel on new routines related to breakfast preparation, meal distribution, waste management and expectations for cleanup—and when?

- Who will conduct refresher trainings or train new staff—and how often?

Student needs: Choose models and related program logistics that account for students’ developmental stages and capacity. For instance, older students are often more independent and may excel with a “grab and go” model, while elementary school students may need more assistance for breakfast in the classroom. Additionally, many special educators report that making the transition with minimal changes to activities, breakfast packaging and even menu items helps prevent behavioral challenges. Consider:

- Which blend of models will best allow schools to execute successful programs?

- How will the program meet the unique needs of different student populations, such as students with disabilities?

- Who will train students on new morning routines (such as breakfast pickup locations and cleanup expectations) and when?

“Every custodian is going to have his or her own different style. Every school is going to be slightly different. You have schools that are two stories and three stories and stuff like that. So school staff know best how to get it done.” —Elementary school custodian, West Virginia

Tailor the program to fit your schools

Introduce the plan to schools by hosting information sessions on the district’s goals. Next, conduct training that clarifies how the program is intended to function. Whenever possible, training should include a dry run so staff can see the program in action and address any potential oversights. Food service leaders are often best equipped to develop and conduct trainings for faculty and staff, while educators may prefer to train students. As each school learns more, seek feedback and examine opportunities to reallocate resources, shift schedules, revisit objectives, clarify roles, strengthen training and expectations, or otherwise adjust and directly respond to anticipated challenges.

Launch!

Once all school staff members are comfortable with the expectations and logistical details related to their transition, communicate to the broader public about the official launch date, the impetus for shifting the breakfast service model, and the district’s goals for the new program. Robocalls, school welcome packets, newsletters and the school website can all help announce the change to parents and families. Solicit volunteers to help on the launch day or with other transition activities. Let students know that breakfast service will soon change, using posters, contests, giveaways and loudspeaker announcements. The launch may also provide a timely opportunity for student champions to encourage their peers to eat more school meals and to offer input on breakfast menu items. Sharing content with local press outlets, community newsletters and listservs may further generate support.

Districtwide excellence

The Syracuse City School District in New York is a “top performer” in school breakfast, ensuring its more than 10,000 low-income students are offered a nutritious morning meal every day.[1] Breakfast after the bell models are a key component of Syracuse’s success, along with the following factors:

- Through the Community Eligibility Provision program—which allows high-poverty schools to offer meal service to all students at no charge, regardless of economic status—every SCSD school offers free breakfast and lunch to every student. The district offers a snack and an evening meal to all students (through the Child and Adult Care Food Program). Finally, a partnership with the local grocer brings nutrition education to elementary schools about the importance of fruit and vegetables.

- Syracuse’s vision for students’ food security accommodates variation in its 33 schools. Each principal may choose to use traditional cafeteria service, breakfast in the classroom, vending machines or a hybrid model. Nineteen schools are choosing to do breakfast in the classroom and eight are offering breakfast in vending machines.

- For large schools, the Syracuse Teachers Association (STA) coordinates with the district to ensure each food service worker is given an additional 10 minutes of morning preparation time for every 200 students served. STA also facilitates early arrivals for days when breakfast service includes many menu components so food service personnel have adequate preparation time.

- Despite school-level variability, Syracuse maintains efficient routines. For example, annual training ensures that food service staff, cooks and recess staff are ready to support any school and model. Moreover, the union, the food service director, building leaders, custodians and cafeteria managers regularly connect to improve the program and discuss other topics, such as the impact of menu changes.

[1] Food Research & Action Center. (2016) “School Breakfast: Making It Work in Large School Districts.” http://frac.org/research/resource-library/school-breakfast-making-work-large-school-districts-sy-2014-2015.

Strategies for a Productive Classroom

“We try to ask the students to eat and do their morning routine at the same time (i.e., clocking in, checking planners, etc.)” —Paraprofessional for adult learners, Oregon

Despite the clear benefits gained by students who eat a healthy school breakfast, many educators feel pressure to focus narrowly on improving students’ standardized test scores. Well-designed breakfast after the bell programs complement morning instructional activities, have been shown to improve test scores, and help educators address the whole child.

In some schools using these programs, most often in secondary settings, students arrive to their instructional space with a bagged breakfast. In other schools, breakfast is delivered directly to the classroom sometime during the morning. Educators should establish routines of core activities to be completed each morning so that breakfast service can be accommodated whenever it arrives. Students may:

- Conduct independent work, including “Do Nows,” fluency folders, independent reading or homework review.

- Finish individual, standardized assessments or check in with the teacher one-on-one.

- Review content or build prior knowledge with hands-free teaching aids, such as videos or podcasts.

- Complete classroom assignments, such as reviewing portfolios or handing out missed work to students who were absent.

- Assist with breakfast logistics, such as sweeping, disposing of packaging or wiping down workspaces.

In any classroom, assignments should be differentiated to align with students’ developmental stage, ability and maturity. While students finish self-directed duties, teachers can address important tasks to start the day, such as taking attendance, collecting homework and setting up technology. Additional adults, such as paraprofessionals or parent volunteers, can help to make breakfast service run smoothly by keeping students on task or clarifying expectations.

Breakfast can be a naturally social time, and teachers should choose whether to leverage or redirect this energy. Some educators may encourage students to connect with peers, such as by working in small groups to complete designated tasks or hosting a whole group morning meeting. Others may use timers, a posted agenda or music to direct students’ attention to specific activities while eating. Whatever the classroom procedures, it is important that students are held accountable for completing their responsibilities. The most successful morning routines involving breakfast are flexible and clearly define student expectations.

In the classroom spotlight

One teacher in Texas shares the routine for her fifth-grade classroom:

“For the first hour, we know announcements are going to happen, we’re going to get our morning work done, we’re going to eat breakfast at some point. We just have a list. The first thing we do is shake hands—I greet the kids eye to eye, and that gives me an opportunity to assess. Anything that’s out of routine, I try to handle right there at the door.

“Inside the room, the chairs are already unstacked because I have a chair leader, the pencils are already sharpened, everything’s ready to go on the desk, and I have leaders that have already done that. All the students have to do is go put their backpack up and get their stuff organized. I also have a whole list of routines on the board, such as telling them to take out their homework folder, their planner and whatever we’re working on first, and telling them to put any communication from home in my pink basket. Then, if they say, ‘What are we supposed to be doing right now?’ I would just point at the board to remind them.

“I really think one of the keys to being successful is just having a lot of this routine stuff toward the beginning of the morning so that it lets you be more flexible and think, ‘Well, OK, we’ll just skip that and move to the next activity and then go back to it.’”

Strategies for Maintaining Clean School Spaces

“Students prep tables, fix their own plates and clean up after themselves.” —Preschool teacher, Missouri

Maintaining clean spaces both inside and outside the classroom is critical when operating a breakfast after the bell program. Though breakfast service may shift to new spaces, the cleanliness standards held for the cafeteria should be applied to all spaces where breakfast is served, especially in individual classrooms. Adequate cleaning supplies provided by the school or district, timely trash removal and daily cleaning procedures are all essential. To keep school spaces tidy while operating a breakfast after the bell program, schools can use these tips:

Stock cleaning supplies: Schools should periodically provide cleaning supplies, such as absorbent paper towels, hand and desk wipes, and mini brooms to each school space participating in breakfast service. Consider using interoffice phones or other technology so educators can signal the need for custodial assistance in cases where larger spills cannot be addressed with cleaning supplies provided to classrooms.

Schools can direct custodial service or food service staff to drop off trash bags. In schools with limited custodial capacity, food service staff may distribute trash bags along with breakfast.

Separate liquids: A separate bucket with a lid should be available for students to dispose of any leftover juice and/or milk. If a separate bucket is unavailable, use double-bag trash cans that will contain liquid waste. Strainers that separate cereal from milk can simplify organic waste management, such as ensuring that cereal does not go down the drain in classrooms equipped with sinks. Menu changes may also help minimize challenging forms of waste.

Isolate trash: Once breakfast service is finished, place trash outside of the door for pickup. Alternatively, locate large central waste baskets in hallways and task a student with placing the classroom trash into this larger container. This method is particularly helpful in schools with limited custodial capacity. Trash should be removed from classrooms or hallways promptly. Using carts to transport trash helps to ease waste removal.

Trash cans should have lids to prevent messes should a trash can fall. Lids also are helpful in special education classrooms, where AFT members note that students may attempt to retrieve discarded food items from the trash.

Assign jobs: Students can play an integral role in breakfast cleanup routines, and engaging in these tasks can build leadership skills. Identify specific roles for students to streamline the cleaning of desks and floor spaces. Students can be responsible for their own spaces or charged with broader responsibilities. Common assignments include collecting remaining nonperishable food, wiping desks, sweeping the floor and trash removal. Some AFT members with students as young as 5 years old report that with practice and a structured routine, students contribute to classroom cleanup.

Strategies for Boosting Student Satisfaction

“What they would be eating at home, my population, would be like a bean burrito or atole.” —Elementary school teacher, New Mexico

Exemplary breakfast after the bell programs balance student preferences with a commitment to nutrition standards. Successful menus have a variety of options, reflect students’ cultural tastes and offer items prepared in-house. Food service staff can use several strategies to enhance breakfast after the bell offerings.

Popularize menus: Draw more students into your breakfast after the bell program by developing attractive menus. These tactics often increase a program’s popularity:

- Variety: Increase menu options to improve student choice and buy-in. When possible, implement “offer verse serve,” a policy that allows students to decline certain required food components, to further increase student choice.

- Branding: Mimic the marketing tactics of restaurants by branding items with clever, descriptive labels, such as naming strawberry smoothies “berry blast smoothies” or calling a whole-grain-rich option “all-day energy boosting.”

- Customization: Include menu items that reflect students’ cultural backgrounds. Offering foods that students eat at home could encourage increased breakfast participation. For example, one school in the South offers grit bowls on their school breakfast menu, while some Southwest schools boast breakfast burritos as a menu favorite.

- Taste tests: Prior to committing to a new breakfast item, consider including students from the student council, a local wellness committee or another organized student group in a taste test. Offer breakfast item samples during the lunch hour and gather feedback. Ask about elements that the students like or don’t like to guide future breakfast item selections.

- Data: Identify ways to improve the current breakfast menu through a brief survey. In many breakfast after the bell models, instructors are present while students eat. Connect with teachers, paraprofessionals and students about which items are the most and least popular on the current menu.

Maximize nutritional quality

Consider preparing more breakfast items in-house, such as hard-boiled eggs, oatmeal cups, low-sugar muffins or smoothies, to increase the availability of scratch-cooked items and decrease the use of processed foods. Discuss with stakeholders what advances have been made to incorporate locally procured food and more fresh fruits and vegetables. Leverage farm-to-school offerings as a way to bring in locally sourced, fresh goods into breakfast, such as cheeses, yogurt, fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

Evaluate Program Success

“My school provides all students with free breakfast, which we have done for a few years. Our campus is huge, and breakfast is served in only one area, near the bus loop. Kiosks might help students arrive to class on time.” —High school teacher, Florida

Breakfast after the bell programs are often promoted because they boost the number of students receiving school meals and they support the learning environment. These programs also typically impact many other aspects of school operations. To sustain a strong program, your district’s leadership team should examine how the program contributes to student well-being and look for opportunities to improve logistics. (For more on district leadership teams, see “Set Up Your Program for Success”) Collect, analyze and apply stakeholder input to reveal important information about the capacity and resources necessary to implement the program effectively. Timely program modifications can boost stakeholder satisfaction, reduce schools’ adjustment time and promote program sustainability and efficiency.

Identify program goals

Determine the questions you seek to answer about the impact of the breakfast after the bell program, such as:

- Is the program reaching more students?

- Is the program reaching the most vulnerable students (those who qualify for free or reduced-price meals)?

- How does the program support academic achievement?

- Are school building spaces clean?

- Are stakeholders satisfied with the program?

Select key metrics

Generally, when evaluating a breakfast after the bell program, two types of metrics can be analyzed: student outcomes and quality improvement. Measuring student outcomes, such as breakfast participation, attendance and tardiness rates or academic achievement, is a great way to show the impact of a breakfast program on the learning environment. Quality improvement data, such as cleanliness or stakeholder satisfaction, are valuable for identifying and addressing any logistical challenges. A robust evaluation should include metrics to measure both student outcomes and quality improvement opportunities.

Collect and analyze data

Consider using data already collected by the school or district. If needed, discuss options for gathering additional data. School personnel are powerfully positioned to observe daily operations and are often keen to communicate school-specific strategies for improvement. Interviews and focus groups can help to reveal satisfaction levels and logistical challenges that may not be captured with a survey. Analyze data over time and by subgroups, such as profession, school and grade level, to uncover unique perspectives and patterns. Share the findings with the full district team to identify opportunities to streamline program implementation and to highlight program successes.

Table 2 offers recommendations on how and when to collect data for potential metrics.

Engage stakeholders

When collecting, analyzing and reporting data, the district team should connect with diverse stakeholders. Strategize about the best ways to include the entire school community in evaluation efforts, including decision makers, teachers working with students of diverse developmental capabilities, custodial and food service staff, parents and students. Moreover, be clear about the expectations for the collection of any new data and how the data will be used to improve the program.

Engage students, families, staff and the broader public with annual reports that:

- Acknowledge staff, such as through co-workers’ or students’ words of praise;

- Announce positive student outcomes;

- Credit relevant team members, staff or partners with their roles in success; and

- Explain program growth through coordinated quality improvement.

Finally, consider sharing press releases or promotional materials with district leaders, partners and local media outlets to acknowledge successes, generate positive coverage and build enthusiasm.

Evaluation supports a smooth transition

As Meriden Public Schools in Meriden, Conn., transitioned to “grab and go” and vending models, the superintendent and director of food and nutrition services explained to stakeholders that they aimed to:

- Evaluate positive outcomes of increased school breakfast participation;

- Obtain positive and negative feedback regarding participation in, and support of, the program; and

- Determine action steps for improvement.

With a district food services staff member on-site “every day until we were confident the [school-level cafeteria] staff could handle it alone,” they ensured that schools were satisfied with program logistics. Additionally, the district relied on a strong labor-management partnership and surveys of parents, students and teachers to make small changes and accommodate the needs of specific buildings and staff, such as adjusting the location of “grab and go” carts.

Take Your Breakfast After the Bell Program to the Next Level

Breakfast after the bell programs offer excellent opportunities to help students cultivate leadership qualities and introduce them to new fresh fruits and vegetables. The National Farm to School Network and the Center for Green Schools provide district leadership teams with tools and resources to elevate breakfast after the bell programs with local foods and environmentally friendly procedures.

Farm to School

“I’m a firm believer in variety. There are so many other options they could get. You know, fresh fruits—I would like to see more bananas and more other fruits and vegetables. I’d like to see hard-boiled eggs. We had those one time, and they absolutely loved them. Maybe yogurt—that’s a protein they can have.” —Preschool cafeteria manager, Illinois

Farm-to-school offerings enrich the connection communities have with fresh, healthy food and local food producers by changing food purchasing and education practices at schools, as well as early childhood education and care sites. More than 42,000 schools across all 50 states and Washington, D.C., report benefits of farm to school, including increased participation in school meal programs, lower school meal program costs and reduced food waste in the cafeteria. There are ample opportunities to integrate farm-to-school activities in breakfast after the bell programs, which can help achieve exemplary menus and increase student willingness to try new foods. Here are three simple ideas for integrating farm to school into your district’s breakfast service.

Incorporate local foods: Food service personnel can generate excitement for breakfast menus by incorporating local foods. In addition to fruits and vegetables, local food products can include proteins, beans, dairy, herbs, grains and more. Here are a few things to keep in mind as you start exploring options to use local items in your breakfast program:

- Define “local.” You get to decide. Local can mean from your county, your state or your region. Consider your area’s growing season and the types of foods grown and produced near you.

- Explore different procurement options. Buying local can mean purchasing directly from a producer, requesting items through your food service provider, or sourcing products from a third-party distributor, farmers market or grocery store food hub.

- Start small. Start by focusing on one local item to include in just one meal, and building up from there. Create a flexible menu that easily allows you to switch in whatever is fresh and in season.

Farm to school in action

Boston Public Schools brings farm to school into breakfast by offering students a healthy muffin that features local apples, zucchini and carrots. Muffins are a versatile product that can easily incorporate many in-season food items (e.g., strawberries in the spring, pumpkin in the fall) and are easily portable for students eating breakfast outside of the cafeteria.

Consider how other local foods, such as yogurt cups, applesauce, whole fruit, berries, potatoes, honey, maple syrup, granola, cream cheese, locally baked bagels, English muffins, tortillas and whole-grain breads, can be incorporated into breakfast service.

Serve student-grown produce: While your school garden may not produce enough food to make up a large portion of the breakfast menu, food service personnel can consider using student-grown produce to increase student engagement and as a tool for nutrition education. Simple ways to integrate school garden produce into breakfast items may include herbs in scrambled eggs, berries with yogurt or tomatoes for fresh salsa alongside a breakfast burrito.

Connect to curriculum: Educators can help healthy habits take root by connecting classroom curriculum to the fresh, local food served for breakfast. While farm to school is a natural fit for science, math and geography lessons, there are no limits to food, nutrition and agriculture-based education. Utilizing farm-to-school principles to teach language, health, visual arts, cultural history and more reinforces healthy eating and fosters educational diversity and creativity both inside and outside the classroom.

Integrating farm-to-school activities in breakfast after the bell programs can be a highly beneficial strategy for developing healthy, appetizing menus and nourishing students for a full day of learning. To learn more about farm to school and to explore resources for implementation, visit http://www.farmtoschool.org.

Take Your Breakfast After the Bell Program to the Next Level

Breakfast after the bell programs offer excellent opportunities to help students cultivate leadership qualities and introduce them to new fresh fruits and vegetables. The National Farm to School Network and the Center for Green Schools provide district leadership teams with tools and resources to elevate breakfast after the bell programs with local foods and environmentally friendly procedures.

Green Schools

“Composting and recycling should go along with breakfast. I wish there was more information in the hands of teachers and administrators about the importance of healthy meals, particularly breakfast, as it relates to academic achievement. I believe connecting healthy food to academics is a way to speak the same language and mutually achieve our goals.” —School district sustainability coordinator, North Carolina

Green schools sustain the world students live in, enhance their health and well-being, and prepare them to be leaders who embrace global sustainability. Schools and districts that embrace these principles, including the nearly 100 school districts participating in the Center for Green Schools sustainability network, model healthy personal choices that are also good for the earth, including through breakfast after the bell programs.

Divert waste from landfills: A study in Minneapolis found that schools generate an average half pound of waste per person per day, about one fourth of which is food.[1] Green schools significantly decrease their carbon footprint by diverting common items from the trash. For instance, plastic bottles and cardboard can be recycled while organic food waste, liquids and nonrecyclable paper can be composted.

- Dig deep. Identify the kinds of materials tossed with a waste audit. Then conduct interviews and site visits to identify opportunities to use less, use items more efficiently or better divert waste. California’s Integrated Waste Management Board developed “Seeing Green Through Waste Prevention” to guide school districts.

- Start at the source. Successful waste management programs begin with purchasing food that has less packaging and can be easily separated into compostable, recyclable and landfill containers. For example, food that comes in a single container made of a single type of material (paper or plastic, aluminum or cardboard), instead of a combination of multiple materials, is easier to sort.

- Sort in the classroom. Implement procedures to sort waste before it is removed from the classroom. Use separate bags in the classroom to collect landfill, recyclable, compostable and unopened food items. Alternatively, set up sorting stations in a central location right outside the classroom, allowing students to quickly toss trash, paper, plastic, compost and food donation items in separate containers.

Recycling champions

Approximately half of the Clark County School District’s schools implement breakfast after the bell programs, and many teachers and students participate in recycling and sorting waste. Classes grab breakfast each morning from a set point, typically a multipurpose room, and students eat in the classroom. After they are done eating, students empty excess food into 5-gallon pails with liners, both provided by the food service department. Empty food and drink containers are placed in classroom recycling and landfill baskets, and custodians pick up the baskets each night. “Teachers model emptying the food and drink containers and monitor appropriate behavior until the students get it right,” says the district’s sustainability coordinator. “It usually only takes a couple of days and the kids are recycling champions!”

Learn more about the important role of district sustainability coordinators with Center for Green School’s 2014 report, “Managing Sustainability in School Districts.”

[1] Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. (Sep 2010). “Digging Deep Through School Trash: A waste composition analysis of trash, recycling and organic material discarded at public schools in Minnesota.” https://www.pca.state.mn.us/waste/school-waste-study.

[2] Feeding America explains how the Good Samaritan Food Donation Act encourages strong partnerships for food donations: http://www.feedingamerica.org/ways-to-give/give-food/become-a-product-partner/protecting-our-food-partners.html?referrer=https://www.google.com.

Facilitate food sharing: Redistributing unopened food served through the school meals program to those in need can minimize food waste. While both the Good Samaritan Food Donation Act[2] and the National School Lunch Act allow and encourage schools to donate surplus food to local organizations or families, school faculty and staff must pay careful attention to local health code regulations. Contact local health officials to understand any existing regulations at the district, county or state levels.

- Make a strong plan. Food donation programs often rely on a strong community partner willing to collect and distribute unopened food. To ensure that trash does not contaminate donations and that food is held at the correct temperature for safety, school personnel should clearly instruct students on how to sort food waste and designate a monitor for food collection.

- Make it work for breakfast. Even for schools with successful food share tables or donation bins in the cafeteria, different strategies are helpful for breakfast after the bell programs with service in instructional spaces. Though cafeterias generally collect all donations in one place, classrooms typically benefit from several collection points. Furthermore, whereas sorting is a student responsibility in most cafeterias, teachers are often responsible for correctly sorting items in classroom-based service. Finally, to facilitate the quick transport of food from the classroom to refrigerators, schools should establish and communicate clear staff roles and procedures that take into account the building layout, kitchen equipment and custodial contracts.

Schools significantly impact resource use in their communities. A breakfast after the bell program is a great opportunity to show students that their future and the future of the environment matters.

Acknowledgments

This guide was developed by Chelsea Prax at the AFT; Mieka Sanderson, formerly of FRAC, now at USDA; and Crystal FitzSimons at FRAC. AFT’s Lauren Samet, Jennifer Scully and Melanie Hobbs reviewed the guide. AFT and FRAC would like to thank Anna Mullen with the Farm to School Network and Anisa Heming with the Center for Green Schools for contributing sections to the guide.

The authors appreciate and value the time AFT union members and leaders contributed in support of this guide. In particular, we thank the Meriden Federation of Teachers, Syracuse Teachers Association and United Federation of Teachers for thoughtful reflections on successful aspects of district programs, which inform several case studies. We also thank the members of Albuquerque Teachers Federation, Houston Federation of Teachers and Spring Branch AFT who shared their perspectives in focus groups.

About AFT

The American Federation of Teachers is a union of professionals that champions fairness; democracy; economic opportunity; and high-quality public education, healthcare and public services for our students, their families and our communities. We are committed to advancing these principles through community engagement, organizing, collective bargaining and political activism, and especially through the work our members do.

About FRAC

The Food Research & Action Center (FRAC) is the leading national organization working for more effective public and private policies to eradicate domestic hunger and undernutrition. For more information about FRAC, or to sign up for FRAC’s Weekly News Digest and monthly Meals Matter: School Breakfast Newsletter, go to: frac.org.