Ida B Wells. W.E.B. Du Bois. Thurgood Marshall. Toni Morrison, Stacey Abrams, Kamala Harris. Oprah Winfrey.

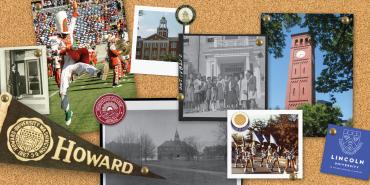

These are just a few of the accomplished graduates of historically Black colleges and universities, but there are millions more whose experiences, while not quite as high-profile, have been just as profound for them and their communities. Now the AFT is more connected than ever to that legacy, as the union welcomes 17 HBCUs to our higher education family. The schools come through the American Association of University Professors’ affiliation with the AFT, and they join two existing AFT HBCU locals—Alabama State University and Florida A&M.

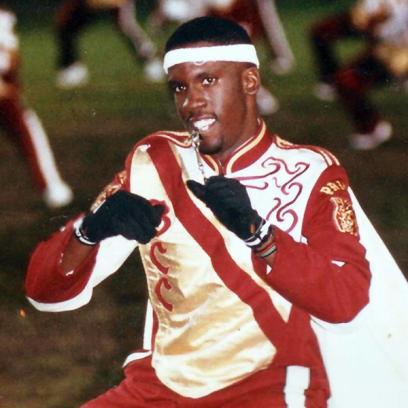

HBCUs play an increasingly powerful role in higher education. “Half of our country’s Black doctors, lawyers and teachers turn their tassels at an HBCU,” says AFT Secretary-Treasurer Fedrick Ingram, a proud graduate of Bethune-Cookman University, a historically Black university in Daytona Beach, Fla. Countless business owners, engineers, executives, academics and artists attend these colleges. They are especially well-represented among AFT members: A LinkedIn poll shows that 16 percent of HBCU graduates go into education, and another 13 percent go in healthcare.

Why HBCUs?

Academic excellence is a leading reason students gravitate toward HBCUs, but there are others as well. “Every day I swam in the waters of Black excellence, and it made my chest swell with pride,” writes Ingram. “I’m not here to say that every Black child must attend a Bethune-Cookman, Hampton or Howard, or that predominantly white institutions are somehow subpar. But I do feel that foundational pride and excellence is a unique gift given only by the halls and campuses of HBCUs.”

Florida Education Association Secretary-Treasurer Nandi Riley, who attended and then taught at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University in Tallahassee, Fla., got the individual attention she needed at her historically Black university. As a young freshman at Florida State University, a predominantly white institution, she was “overwhelmed” by auditorium classes with hundreds of students. “There was no way the professor knew who I was,” she remembers now, and she didn’t understand she could meet them during office hours. Her experience at Florida A&M, where students were not expected to be quite so independent, was “totally opposite.”

HBCUs can be “more like family,” says Denise Gaither-Hardy, president of the AAUP Chapter at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and a professor of psychology. “HBCUs provide students with an opportunity to flourish and excel without the added pressure of fitting into a culture that’s not their own.”

Today, more and more students choose HBCUs. While higher education admissions overall dropped 3.2 percent between 2020 and 2022, HBCU admissions went up by 2.5 percent. HBCU applications rose 30 percent between 2018 and 2021, and the number is rising.

Why the increase? Some students experience predominantly white institutions becoming “more inhospitable in terms of their ability to even admit Black students, but also their ability to provide programming that is appealing and welcoming to Black students,” says Andrew Douglas, a member of the AAUP’s committee on historically Black institutions and scholars of color, and a political science professor at Morehouse College in Atlanta. HBCUs also appeal to those who believe higher education should serve the public good, he adds. Though not every campus lives up to that ideal, he feels HBCUs have more potential to “protect and steward an idea of education as a public good, an idea of education for a democratic citizenry.”

Making a way out of no way

HBCUs rose up out of necessity. Historically, enslaved people were forbidden by law from reading, much less attending school or college. Enslavers feared a literate person could more effectively resist enslavement, as abolitionist Frederick Douglass explained: “Once you learn to read you will be forever free.”

Black Americans knew this, and so they managed to educate themselves despite the odds. In the tradition of making a way out of no way, Black churches and other civic organizations established schools for Black children. And in the early 19th century, they helped establish the first HBCUs.

Today, the United States has 100 HBCUs, approximately half public and half private. They include research-based, land-grant, religious and liberal arts schools and range from 300 to more than 11,000 students. They are known for having large numbers of students from low-income families and many who are the first in their families to attend college.

Continued inequity

But while HBCUs have long provided a place for Black students to pursue higher education, the institutions’ resources often fall short.

Like the absence of generational wealth created by the legacy of enslavement and Jim Crow discrimination, HBCU wealth is also limited. A Forbes magazine study shows that the average endowment at Black land-grant schools was $34 million in 2020, compared with $1.9 billion–that’s billion with a “b”—at white land-grant schools.

Why do Black graduates give less to their alma maters? Typically, they have less money to give. Black workers face discrimination that can slow high-paying careers. Student debt also plays a role: Black college graduates typically owe $25,000 more in student loan debt than white college graduates, and four years after graduation, nearly half of Black borrowers owe 6 percent more than they borrowed. Performance-based state funding is another problem: If state money hinges on six-year graduation rates, for example, HBCUs, where students’ life circumstances may prevent them from graduating “on time,” will lose out.

The Forbes study shows the federal government is also failing to fund land-grant HBCUs equitably. “Black land-grant universities have been underfunded by at least $12.8 billion over the last three decades,” the study says. Forbes describes outdated heating and cooling systems and peeling paint at HBCUs, and gleaming research and athletic facilities at predominantly white institutions.

Moving forward in solidarity

Despite some neglect, HBCUs have risen in popularity, as people like Kamala Harris and the late Chadwick Boseman publicly celebrate their traditions and cultures, raising the profiles of other proud alumni and increasing awareness and prestige. These schools are more crucial than ever in providing pathways to educational advancement that are more accessible. And as state laws threaten the freedom to teach Black history, negating Black experiences, HBCUs can feel like sanctuaries for Black students—and Black faculty and staff.

“There is a rise in racism across all educational systems,” says Gaither-Hardy. “I would say the need for Lincoln University and all HBCUs is stronger than ever. It’s a place of higher learning that Black folks can attend without many of the subtle and not so subtle racist acts currently alive and well on PWI campuses.”

And unions will continue to provide avenues for achievement within those structures. While HBCUs offer many advantages, they are not perfect, says Gaither-Hardy. “It’s unwise to believe that an administration is always going to do what is in the best interest of its faculty and staff, because many times this goes against a bottom line of funding,” she says. What’s more, administrations come and go. “A union provides the stability that is needed to continue the work of educating students at the highest levels.”

“Our faculty recognizes that the union can be a voice when their voice alone may not be heard,” she says. That is true in any workplace, HBCU or otherwise.

[Virginia Myers]