Increasing Civic Engagement

Civic engagement has recently gained attention as a key social determinant of health, informing the new Healthy People 2030 core objective to increase the number of citizens who vote.1

Through voting, people can participate in decisions that directly and indirectly affect their health—for instance, voting on ballot initiatives that expand access to Medicaid and reproductive healthcare or clean water and green community spaces. That’s one reason communities with high voter turnout tend to have better self-reported general health, fewer chronic health conditions, greater social inclusion and sense of belonging, and lower overall mortality rates.2

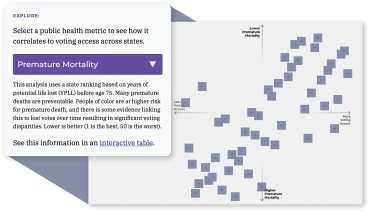

The Healthy Democracy Healthy People coalition’s Health and Democracy Index (democracy index.hdhp.us) shows a clear connection between voting and health in the United States. The index compares the Cost of Voting Index (COVI) for the 2020 general election with health outcomes and voter turnout in each state. Factors that influence the COVI calculation include voter registration deadlines and restrictions, voter ID laws, voting inconvenience, and poll hours. Among the 12 health outcomes measured were self-rated general and mental health, chronic disease prevalence, infant and premature mortality, poverty, and community and family safety. States with lower COVI (indicating fewer barriers to voting) showed better health outcomes than states with higher COVI. On the interactive website, you can see how each health outcome relates to voting access. As shown below, premature mortality has a strong association with voting barriers.

What Healthcare Workers Can Do

While voter participation across the nation has improved, 33 percent of eligible voters did not vote in the 2020 election and half did not vote in the 2022 election3—and some healthcare professionals are less likely to vote than the general population.4 But the 2024 election is a renewed opportunity to build support for policies that ensure an inclusive, representative democracy and healthier communities.

There are several ways that healthcare professionals can help improve public health outcomes through improving civic engagement:

- Vote in upcoming local, state, and federal elections.

- Encourage friends, family, and colleagues to vote.

- Talk to patients—in nonpartisan ways—about the importance of voting and share voter registration information (visit vot-er.org/resources for help).

- Help hospitalized patients get emergency absentee ballots (visit patientvoting.com for more information).

Addressing Discrimination

Racism and discrimination severely impact health. Numerous studies have documented poorer health outcomes for people from racial and ethnic minority groups5 and noted that discrimination based on race, ethnicity, and language differences limits patients’ access to and quality of healthcare.6 A recent report, “Revealing Disparities: Health Care Workers’ Observations of Discrimination Against Patients,” extends this research with concerning findings about discrimination in healthcare settings.

In early 2023, the African American Research Collaborative and the Commonwealth Fund surveyed 3,000 healthcare workers employed in inpatient and outpatient care facilities across the country. More than half (52 percent) indicated that racial or ethnic discrimination against patients was a major problem or crisis in their workplace, and 47 percent reported witnessing discrimination against patients—with most witnessing it in the past three years. This number was higher for workers under age 40, those in mental health settings, and those in facilities serving majority-Black or majority-Latinx patients.

More than half said that certain patient groups experienced healthcare discrimination or inequitable treatment from care providers, including Black patients (55 percent of respondents); patients with mental health needs (61 percent); patients with low income or no health insurance (62 percent and 55 percent, respectively); patients who identify as transgender, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming (57 percent); and patients whose primary language was not English (60 percent). About half reported that care providers were less likely to accept health self-advocacy—which is related to better health outcomes7—from patients of color than from white patients.

Racial and ethnic discrimination also impacted healthcare workers, with most experiencing stress related to discrimination. Those who worked in facilities serving majority-Black or majority-Latinx patients were more likely to report “a lot” of stress—and Black and Latinx healthcare workers experienced much higher rates of stress than white healthcare workers and were more likely to fear negative consequences for reporting racism or discrimination in their workplaces.

While 60 percent of healthcare workers had received anti-discrimination training, the majority agreed more should be done to address discrimination in healthcare settings. The strategies they believed to be most effective included providing more opportunities for healthcare workers to learn to spot discrimination (79 percent of respondents), implementing confidential reporting for those who experience or witness discrimination (74 percent), examining organizational policies to ensure equitable healthcare outcomes for patients of color (71 percent), and creating opportunities for organizations to listen to patients and healthcare workers of color (69 percent).

To learn more, read the report at go.aft.org/gz3.

Endnotes

1. Healthy People 2030, “Increase the Proportion of the Voting-Age Citizens Who Vote—SDOH‑07,” US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/social-and-community-context/increase-proportion-voting-age-citizens-who-vote-sdoh-07.

2. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 2023 County Health Rankings National Findings Report: Cultivating Civic Infrastructure and Participation for Healthier Communities (Madison: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2023), countyhealthrankings.org/findings-and-insights/2023-county-health-rankings-national-findings-report; and C. Nelson, J. Sloan, and A. Chandra, Examining Civic Engagement Links to Health: Findings from the Literature and Implications for a Culture of Health (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019), rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR3100/RR3163/RAND_RR3163.pdf.

3. Pew Research Center, “1. Voter Turnout, 2018–2022,” July 12, 2023, pewresearch.org/politics/2023/07/12/voter-turnout-2018-2022.

4. R. Solnick, H. Choi, and K. Kocher, “Voting Behavior of Physicians and Healthcare Professionals,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 36, no. 4 (April 2021): 1169–71.

5. Office of Health Equity, “Racism and Health,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, September 18, 2023, cdc.gov/minorityhealth/racism-disparities/index.html; and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, “The State of Health Disparities in the United States,” in Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity, ed. J. Weinstein et al. (Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017), ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844.

6. N. Ndugga and S. Artiga, “How Recognizing Health Disparities for Black People Is Important for Change,” KFF, February 13, 2023, kff.org/policy-watch/how-recognizing-health-disparities-for-black-people-is-important-for-change; and C. DeGuzman, “Many People of Color Worry Good Health Care Is Tied to Their Appearance,” KFF Health News, December 5, 2023, kffhealthnews.org/news/article/health-care-quality-race-appearance-kff-survey.

7. J. Hutchens, J. Frawley, and E. Sullivan, “Is Self-Advocacy Universally Achievable for Patients? The Experiences of Australian Women with Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy and Postpartum,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 18, no. 1 (2023): 2182953.