Feedback

Feedback on work or performance can move students to improve and excel. Effective feedback to students has three primary qualities. It must be timely, specific and credible. Praise for that which is not worthy will destroy its value. Praise for everything makes it impossible for students to know the quality of their work. Praise for effort should not be confused with praise for results.

Feedback is about the work, not the student. According to research, it should force the student to engage cognitively in the work. (Black and Wiliam; Thompson) The questions posed by the teacher should point them to missing or erroneous information and provide a clue (not a prescription) for how to proceed to make the work better. Pointing out what specifically students did well also serves as motivation to keep going. The task remains doable. For example, saying, “You used words that help me see precisely what is happening” or “Your calculations seem to be correct, but I can’t tell what your answer means. Please label what you have found out. What is your answer to the question?” can help students grow. “Great work!” or “keep trying” do not provide clues about what is done well or needs improvement.

Vocabulary Development

Vocabulary development is essential for all subjects. Students should be engaged, not just in the memorization of definitions but in thinking about what words mean in specific subjects or circumstances and what they do not mean. One model for approaching vocabulary in content areas is to develop the concepts behind the words first, and introduce the words when students understand.

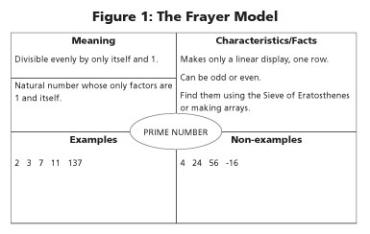

Available word walls, posting words or phrases on the wall, for frequent brief review or reference is a strategy for reinforcing vocabulary. A written model for students to keep and study from is the Frayer model. On a paper folded into four quadrants, students write the important word or phrase in the center. They write their own definition in the upper left, characteristics in the upper right, an example of the word in the lower left and a non-example in the lower right. Then the class comes up with a class definition that is written below the students’ own definition (see Figure 1). This model can help move the student to a more formal and perhaps more precise understanding of the word.

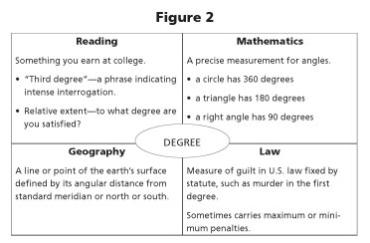

The model can also be used to examine meanings of words in cross-curricular settings (see Figure 2).

Working Together—Cooperative Groups/Teams

Cooperative groups should be formed to work on a task or project to which every member of the group can contribute something. Multi-ability tasks or projects enable students with different strengths and talents to contribute to the work. The abstract thinker may be less gifted at creating a display for the group’s findings or making the mathematics visible. It is important for the instructor to let students know everyone is expected to contribute to a group project.

It is wise to assign responsibilities within a cooperative group and teach appropriate behaviors. One set of responsibilities, depending on the task, could be:

- Facilitator – responsible for keeping the group on task and seeing that norms for behavior are followed;

- Materials person – responsible for getting and returning any materials the group needs;

- Recorder – keeping a written record of the group’s work or thoughts so they can be reviewed, summarized or conveyed to others; and a

- Reporter – who presents the group’s findings to the rest of the class. Sometimes each group member will be involved in the presentation. In this case, the job may be that of checking that everything is in order and ready.

Other jobs may include art or poster preparation, researcher, timekeeper or encourager. Assignments to groups can be done in a number of ways: voluntary association (which may leave some students out), assigning students with various achievement levels or strengths to a group, self-selection by the particular project they want to pursue or random selection by icebreaker-type activities. Regardless of how groups are assigned, it is important that there is someone in the group who can assume a leadership role. It is also important that students understand the nature and expectations of any roles assigned. This may require mini-lessons and modeling.

Students must also understand the norms of behavior during project work (and at other times). Norms are rules for how people should behave in given circumstances. When working collaboratively, students “must learn to ask for other people’s opinions, to give other people a chance to talk, and to make brief sensible contributions to the group effort.” (AFT, 1994) General norms might include:

- listening respectfully to each other;

- contributing;

- asking for help when needed;

- helping when asked; and/or

- being aware of safety considerations.

Behaving according to the norms that are set will help the whole group succeed.

Groups may be given a short group task to accomplish while an observer takes notes on how norms are followed and roles are fulfilled. Feedback to the group will help them become more aware of their part in the group.

Metacognition

One difference between novices and experts is that experts know what they are trying to accomplish, where they are, and what they still need to do. They are also aware of the strategies they use and why they use them. It is important to help students develop the ability to assess where they are and understand what they are doing. Often, providing a graphic organizer of some sort can help them keep track of where they are in a project, what they have done and what they still must do.

In addition to a written note taker, the instructor should frequently probe what groups are doing and why. If a group does not appear to understand the task or a skill they need to use, the instructor must ask questions or provide examples to help move the group along.

Finally, staff need to teach metacognitive strategies within the context of the discipline/subject area being taught. They can model metacognitive strategies by doing “think-alouds” with the students so the students can see the teachers’ thinking processes.

To monitor their own thinking and develop metacognition, students should ask themselves the following questions:

- How is what I’m hearing/seeing like what I already know?

- What do I understand?

- What don’t I understand?

- What comes next? What predictions can I make about the future, or future steps?

- What have I learned that’s new?

(National Research Council)