We stand today in the middle of an important debate on the role, function, and practice of school discipline. There can be no question that any approach we implement should strive to create school climates that are safe, orderly, and civil, and that teach our children basic values of respect and cooperation. The key question revolves around the best way to accomplish that goal.

For some 20 years, numerous policymakers responded to concerns about school safety and disruption with a "get tough" philosophy relying upon zero-tolerance policies and frequent out-of-school suspensions and expulsions. But research has overwhelmingly shown that such approaches are ineffective and increase the risk for negative social and academic outcomes, especially for children from historically disadvantaged groups. In response to these findings, educational leaders and professional associations have led a shift toward alternative models and practices in school discipline.1 District, state, and federal policymakers have pressed for more constructive alternatives that foster a productive and healthy instructional climate without depriving large numbers of students the opportunity to learn.

The recent beginnings of strong models in states, districts, and schools throughout the nation can serve as a guide to more effective and research-based school discipline approaches. Yet there is also resistance to changing the status quo. Bolstered by a get-tough political discourse, some schools and districts have not had the chance to consider effective alternatives to zero tolerance. Educators in environments characterized by excessive suspension rates may see themselves with few alternatives to suspension and expulsion. Therefore, a successful transition toward a positive school climate will require strong support and training for both teachers and administrators.

In this article, we trace the course of school discipline over the past 20 years and examine the status of school discipline reform today. We begin with an examination of zero-tolerance, suspension, and expulsion policies, as well as their assumptions and effects. We discuss alternatives that have been proposed and the guidance that has been offered by the federal government, and examine state changes that may be models for others. Finally, for any new model to be effective, support of teachers and administrators is essential; thus, we consider what educators really need if we are to successfully reform school discipline.

How Did We Get to "Get Tough"?

In the 1970s, suspension rates for students of color, especially those who were black, began to rise, prompting concerns from civil rights groups. In 1975, the Children's Defense Fund published a report, School Suspensions: Are They Helping Children?, about high and racially disparate rates of out-of-school suspensions. Unjust suspensions were also the subject of several court challenges in the 1970s and 1980s.

Pressure to expand the use of suspension and expulsion increased further with the advent of zero-tolerance policies. Growing out of federal drug policy in the 1980s, zero tolerance was intended primarily as a method of using severe and invariant consequences to send a message that certain behaviors would not be tolerated.2 Beginning in the late 1980s, fear of increased violence in schools led school districts throughout the country to promote zero-tolerance policies, calling for expulsion for guns and all weapons, drugs, and gang-related activity, and to mandate increased suspension and expulsion for less serious offenses such as school disruption, smoking, and dress code violations3 (although later research showed no significant rise in school violence in that period4). This movement also resulted in the increased use of security personnel and security technology,5 especially in urban schools.6

In 1994, the federal government stepped in to mandate zero-tolerance policies nationally when President Bill Clinton signed the Gun-Free Schools Act into law, requiring a one-year calendar expulsion for possession of firearms on any school campus. Some states had already passed similar requirements, and many others that adopted the federal law into their state codes of conduct further expanded them to cover much more than the mandated expulsion for bringing a firearm to school.

Ultimately, these policies led to significant increases in disciplinary removal and expansion in inequities in suspension and expulsion rates. Since 1973, the percentage of students suspended from school has at least doubled for all racial and ethnic groups.7 Nearly 3.5 million public school students were suspended at least once in 2011–2012,8 more than one student suspended for every public school teacher in America.9 Given that the average suspension is conservatively put at 3.5 days, and that many students are suspended more than once, these figures mean that U.S. public school children lost nearly 18 million days of instruction in just one school year because of exclusionary discipline.10 While an estimated 6 percent of all enrolled students are suspended at least once during a given year, national longitudinal research indicates that between one-third and one-half of students experience at least one suspension at some point between kindergarten and 12th grade.11

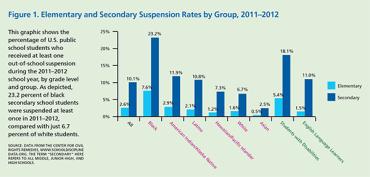

Out-of-school suspension and expulsion, and their associated risks, fall far more heavily on historically disadvantaged groups, especially black students. Data reported on disciplinary removals for the 2011–2012 academic year show that black students face the highest risk of out-of-school suspension, followed by Native American and then Latino students.12 White, Asian, and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students are typically suspended at the lowest rates.

Although the percentage of students who receive at least one suspension in a school year has increased for all groups, that increase has been most dramatic for historically disadvantaged groups, resulting in a widening of the discipline gap. As depicted in Figure 1 below, 7.6 percent of all black elementary school students were suspended from school in 2011–2012, and that rate is 6 percent higher than for white elementary school students (1.6 percent). As the frequency of suspension rises dramatically at the secondary level, this 6 percentage-point difference in suspension rates (the black-white gap) expands almost threefold, becoming a nearly 17 percentage-point black-white gap at the secondary level (middle school and high school). Across the nation, in just one year—2011–2012—nearly one out of every four black students in middle and high school was suspended at least once.

(click image for larger view)

These differences are not simply due to poverty or more severe misbehavior on the part of students of color. Sophisticated statistical models have consistently shown that race remains a significant predictor of school exclusion even when controlling for poverty.13 Nor is there evidence that racial discipline gaps are due to differences in severity of misbehavior; black students appear to be disciplined more frequently for more subjective or more minor offenses and disciplined more harshly than their white peers, even when engaging in the same conduct.14

Other groups are also at increased risk for suspension and expulsion. Discipline disparities for Latino students appear to increase at the secondary level.15 Students with disabilities are suspended nearly twice as often as students without disabilities,16 and are removed for longer periods of time, even after controlling for poverty.17 Although males, in particular black males, are more likely to be suspended,18 black and Latina females are also at increased risk.19 Finally, recent research has found that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students are at increased risk for expulsion, for encountering a hostile school climate, and for being stopped by the police and arrested.20

Another response in U.S. schools to perceptions of increased threat has been the more prevalent use of school security measures, such as video cameras, metal detectors, and increased security personnel. Yet over a 20-year period in which use of these measures increased, there are very few empirical evaluations of their effectiveness. Regardless of perceptions of their effectiveness, the data on school security measures that do exist do not provide support for using such measures to deter violence. Surveys and statistical analyses in the United States have found that schools that rely heavily on school security policies continue to be less safe than schools serving similar communities that implement fewer components of zero tolerance.21 Moreover, qualitative research suggests that invasive school security measures such as locker or strip searches can create an emotional backlash in students.22 More recent studies have found that greater security measures at a school are associated with black students' increased risk for suspension but no benefits to the overall school environment.23 A study of Cleveland's investments following a school shooting found that money spent on security "hardware" did not result in higher safety ratings.24 While a belief that security hardware will instill a sense of safety informs these decisions, survey data, including a controlled study of all of Chicago's schools,25 has found that the quality of student, teacher, and parent relationships was a far stronger predictor of feelings of safety.

What Are the Effects of Suspension and Expulsion?

A large body of research findings has failed to find that the use of suspension and expulsion contributes to either improved student behavior or improved school safety. Schools with higher rates of suspension have lower ratings of school safety from students26 and have significantly poorer school climate,27 especially for students of color.28 In terms of student behavior, rather than reducing the likelihood of being suspended, a student's history of suspension appears to predict higher rates of future antisocial behavior and higher rates of future suspensions in the long term.29 These and other findings led the American Psychological Association to conclude that zero tolerance was ineffective in either reducing individual misbehavior or improving school safety.30

School exclusion also appears to carry with it substantial risk for both short- and long-term negative outcomes. Use of suspension and expulsion is associated with lower academic achievement at both the school31 and the individual32 level, and increased risk of negative behavior over time.33 In the long term, suspension is significantly related to students dropping out of school or failing to graduate on time.34

Finally, exclusionary discipline appears to be associated with increased risk of contact with the juvenile justice system. The Council of State Governments' report Breaking Schools' Rules: A Statewide Study of How School Discipline Relates to Students' Success and Juvenile Justice Involvement found that suspension and expulsion for a discretionary school violation, such as a dress code violation or disrupting class, nearly tripled a student's likelihood of involvement with the juvenile justice system within the subsequent year.35 Together, these data show that out-of-school suspension and expulsion are, in and of themselves, risk factors for negative long-term outcomes.36

Alternative Strategies

The good news is that a number of universal, schoolwide interventions have been found effective in improving school discipline or school climate and have the potential to reduce discipline disparities based on race.37 Such strategies address three important components of school climate and school discipline: (1) relationship building, through approaches such as restorative practices; (2) social-emotional learning approaches that improve students' ability to understand social interactions and regulate their emotions; and (3) structural interventions, such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or changing disciplinary codes of conduct.

Relationship Building. Interventions that focus on strengthening teacher-student relationships can reduce the use of exclusionary discipline, particularly for black students. For example, MyTeachingPartner, a sustained and rigorous professional development program focusing on teachers' interactions with students, reduced teachers' reliance on exclusionary discipline with all of their students, and that effect was the most pronounced for black students. Interestingly, although the training did not focus on racial disparities per se, there was a substantial reduction in discipline disparities in the classrooms of teachers who received the training.38

Restorative practices, implemented throughout the school to proactively build relationships and a sense of community and to repair harm after conflict, are beginning to be widely used in schools across the country. A review of teacher and student reports of restorative practices implemented in two high schools found that individual teachers with better implementation of restorative practices had better relationships with their students, were perceived as more respectful by their students from different racial and ethnic groups, and issued fewer exclusionary discipline referrals to black and Latino students.39

After implementation of restorative practices in the Denver Public Schools, suspension rates were reduced by nearly 47 percent across the district, and all racial groups saw reductions, with the largest drops in suspension rates for black and Latino students. During the same period, achievement scores in Denver improved for each racial group each year.40

Social-Emotional Learning. Social and emotional learning programs vary greatly but generally build students' skills to (a) recognize and manage their emotions, (b) appreciate the perspectives of others, (c) establish positive goals, (d) make responsible decisions, and (e) handle interpersonal situations effectively.41 Several studies have linked the completion of social and emotional learning programs to an increase in prosocial behaviors and a decrease in misbehaviors.42

For instance, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District engaged in comprehensive reform efforts that included the implementation of data-driven improvement efforts, districtwide implementation of research-based social and emotional learning programs, and the creation of student support teams that addressed early warning signals such as discipline referrals and attendance issues. Results included improved student attendance districtwide, a 50 percent decline in negative behavioral incidents, and a districtwide reduction in use of out-of-school suspension.43

Structural Interventions. Changing the structure of the disciplinary system can reduce the use of suspension and expulsion, and may reduce disparities in exclusionary discipline. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports* can reduce exclusionary discipline, but specific attention to issues of race and diversity may be necessary if PBIS is to reduce disciplinary disparities. A four-year project implementing PBIS in 35 middle schools showed that schools using proactive support instead of reactive punishment saw reductions in disciplinary exclusion rates for Latino and American Indian/Alaska Native students, but not for black students,44 suggesting that modifications of PBIS may be necessary to reduce racial disparities in discipline.

Another study, through a survey of 860 schools that were implementing or preparing to implement PBIS, identified the most commonly cited "enablers" and "barriers" to using this model. Among the most common enablers were "staff buy-in, school administrator support, and consistency" of a common approach among school personnel, while the most common barriers were lack of "staff buy-in, resources: time, and resources: money."45

Other research has shown that a systematic response to threats of violence can reduce suspensions and racial disparities. Schools across the state of Virginia using the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines, a tiered process of review designed to help schools identify and respond appropriately to the full spectrum of behavior perceived as threatening, were 25 percent less likely to suspend students, and black-white racial disparities in suspension were significantly lower than in schools not using the guidelines.46

Finally, changes in policy at the district level are a key first step in developing more positive and effective school climate. An extensive examination of school codes of conduct found that many of the codes reviewed were rated as punitive/reactive, even for minor behavioral infractions such as repeated tardiness, foul language, dress code violations, or horseplay in the hallway.47 Thus, rewriting district codes of conduct has been a major focus of school discipline reform. A number of major urban school districts, including the Los Angeles Unified School District48 and Broward County (Florida) Public Schools,49 have revised their codes of conduct to eliminate out-of-school suspensions for minor offenses and to focus on preventative alternatives to suspension and expulsion. To ensure success, such revisions should go hand in hand with providing school staff with effective training on these preventative alternatives and the support needed to implement them.

A Comprehensive Model for Reducing Exclusion and Disproportionality

Among the recent national initiatives addressing disproportionality in school discipline has been the Discipline Disparities Research-to-Practice Collaborative, a group of 26 nationally recognized researchers, educators (including the AFT), advocates, and policy analysts who came together to address the problem of disciplinary disparities. After three years of meetings with stakeholders and reviews of the relevant literature, the collaborative released a series of four briefing papers on the status of discipline disparities, with a particular focus on increasing the availability of practical and evidence-based interventions.50 The collaborative also sponsored a major national conference, "Closing the School Discipline Gap," that resulted in an edited volume of papers.51

In the second paper in the series, "How Educators Can Eradicate Disparities in Discipline: A Briefing Paper on School-Based Interventions," Anne Gregory, James Bell, and Mica Pollock present what may be the most comprehensive model to date for addressing disparities in school discipline by focusing on conflict prevention and conflict intervention.52

Conflict in the classroom leading to office referral and possible school exclusion is not inevitable. Rather, a number of strategies can defuse potential conflict and keep students in class:

- Building supportive relationships. Forging authentic relationships with all students communicates high expectations and sends a message that all students will be fairly and consistently supported in reaching those goals.

- Ensuring academic rigor. Offering engaging and relevant instruction, while setting high expectations, has shown remarkable results in dramatically raising the achievement and graduation rate in schools some might regard as too challenging.53

- Engaging in culturally relevant and responsive teaching. By integrating students' racial/ethnic, gender, and sexual identities into curricula, resources, and school events, effective schools find that students feel safer, report lower rates of victimization and discrimination, and have higher achievement.

- Creating bias-free classrooms and respectful school environments. Research on implicit bias has shown that racial stereotypes can influence an individual's judgments, unbeknownst to that individual. For teachers, this means that implicit bias can influence their judgments about a student's behavior.54 (For more on implicit bias, see "Understanding Implicit Bias" by Cheryl Staats.) Gregory and her colleagues suggest that the potential effects of implicit bias—which all individuals, regardless of profession, may hold—can be mitigated by self-reflection, avoiding snap judgments, and examining data on discipline disparities and the key decision points that might contribute to them.55

Gregory and her colleagues point out that some conflict and disruption are inevitable in schools. However, they note that schools can reduce the effects of conflict by targeting "hot spots" of disciplinary conflict or differential treatment in order to identify solutions, examining what caused the behavior or conflict and addressing the identified needs, reaching out to include the perspectives and voices of students and families in resolving conflicts, and implementing procedures to reintegrate students into the learning community after a conflict has occurred.56

Changes in Disciplinary Policy

In response to the accumulating research and growing public awareness of high suspension rates, leading educational professional associations and policymakers have begun to embrace national, state, and local initiatives intended to reduce rates of suspension and expulsion and increase the use of alternatives. Professional associations such as the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics have issued reports on the ineffectiveness of and risks associated with disciplinary exclusion, and have recommended the use of such measures only as a last resort.57 Statements issued by the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association, the National School Boards Association, and the American Association of School Administrators have similarly endorsed a policy shift away from frequent reliance on disciplinary exclusion and toward more constructive interventions.

Research in Texas links frequent and disparate school discipline to a three- to fivefold increase in students' risk of dropping out of school and coming in contact with the juvenile justice system.58 Inspired in part by this research, the U.S. departments of Education and Justice undertook a national initiative, the Supportive School Discipline Initiative, to reduce the use of suspension and expulsion, and the corresponding flow of students into the juvenile justice system.59

This initiative included the departments' joint release of a two-part federal guidance document intended to reduce the use of suspension and expulsion, and the disparities associated with those, and offer guidance on moving toward more-effective alternatives. (For more about this federal guidance, see "School Discipline and Federal Guidelines.") One critically important document was the legal guidance, issued as a 'Dear Colleague' letter to schools and districts, alerting recipients of the need to review discipline policies, practices, and data for evidence of unjustifiable racial disparities, in order to ensure compliance with federal anti-discrimination law.

The legal guidance highlights the importance of the "disparate impact" analysis. To illustrate disparate impact, it uses a policy of suspending students for truancy as an example because of obvious questions about the underlying justification. If suspending truant students was found to burden one racial group more than others, unless the district could show that the suspensions were educationally necessary, it would likely be found to violate federal anti-discrimination law, even if there was no intent to discriminate. As the letter makes clear, even if the school district had some justification for suspending truant students, the policy might still be found to be unlawful if less-discriminatory alternatives were available that were equally or more effective at deterring truant behavior.

With this guidance has also come stepped-up federal review of district discipline practices for possible violations. In several large districts, including Dade County, Florida; Los Angeles and Oakland, California; and Oklahoma City, reviews for compliance with civil rights law have resulted in major changes.

The Center for Civil Rights Remedies' review of federal investigations between September 2009 and July 2012 indicates the level of federal involvement with school discipline.60 As that report notes, there were 821 discipline-based complaints and agency-initiated compliance reviews during that time, of which 789 were resolved. As of fall 2014, 55 of those resolutions resulted in an agreement to address discipline policies and/or practices, with 32 districts currently under investigation. Geographically, discipline-based complaints or compliance reviews were found in all states except Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming.

Ultimately, federal enforcement of disparate impact can help leverage the replacement of harsh and often counterproductive approaches with better policies and practices that help all children. As the research (and contents of resolution agreements) suggests, such changes entail districts providing teachers and administrators the support and training necessary to implement more effective approaches. In its position statement on school discipline, the AFT supports more effective disciplinary alternatives. At the same time, the union emphasizes that to implement these approaches, educators require proper training. This training and professional development must be ongoing, provided to all school staff, and "aligned with school and district reform goals, … with a focus on evidenced-based positive school discipline, conflict resolution, cultural relevancy and responsiveness, behavior management, social justice and equity."61 Similarly, the National Education Association has joined efforts to end school discipline disparities, and both organizations have supported replacing harsh discipline with restorative practices.62

Concurrent with changes at the federal level, states and school districts across the nation have formulated new policies shifting codes of conduct away from punitive and exclusionary practices, and toward comprehensive and restorative approaches. Often driven by local advocates, at least 19 states have passed legislation moving policy and practice away from zero-tolerance strategies toward an increased emphasis on promoting positive school climates.63 (For more on these state and local policies, see Boxes 1 and 2 on the right.)

The Need to Support Educators

Research has led educators and policymakers across the nation to an understanding that exclusionary approaches to discipline are neither an effective nor equitable method for ensuring safe and productive schools for all students. This has led to the development of alternative and more effective strategies in reducing disruption, maintaining a positive school climate, and keeping students in school. Federal, state, and district policies and guidelines have begun to mirror this shift.

But change is rarely an easy, straightforward process. When it comes to school discipline, effective implementation of new approaches typically depends upon substantial levels of support for educators and schools. In particular, where remedies call for widespread systemic change, in order to successfully replace counterproductive practices with more effective disciplinary alternatives, it is critically important that educators be fully supported with resources and training.

Professional Development and Technical Assistance. As noted, numerous strategies for maintaining safe and productive school climates are emerging as more effective alternatives to suspension and expulsion. In order for teachers to integrate these strategies into their instruction, schools and districts must ensure that sufficient time for professional development and technical assistance are available to train and coach teachers in implementing such approaches as restorative practices, culturally responsive approaches to PBIS, social and emotional learning, implicit bias training, and culturally responsive classroom management.

Some professional development on positive discipline strategies can be integrated into ongoing school and district professional development schedules. In other cases, however, implementation of new programming will require additional training and resources (e.g., teacher release time) to ensure adequate training in new practices, and especially guidance on how those strategies can be best fit within (not in addition to) existing instructional time. Teacher-to-teacher support programs, such as professional learning communities or mentoring, are also important.

Administrative Support. Instructional leaders must stand by teachers throughout this process. The Blueprint for School-Wide Positive Behavior Support Training and Professional Development from the National Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports includes strong support from a district leadership team among the criteria for implementing PBIS with fidelity. With the backing, support, and commitment of administrators, school districts can avoid the myriad problems often associated with mandated changes.

Ongoing Collection of and Access to Disaggregated Discipline Data. There are three reasons why data collection and reporting are also essential. First, within most districts, disciplinary approaches, the frequency of suspensions, and the ensuing disparities can vary greatly. Thus, data can establish baselines describing current areas of need, as well as schools that are doing well. If schools do not routinely pay attention to their discipline data, it will be difficult to respond and build upon what is working in a timely manner, or to modify a policy that is not working as well as expected. Second, data enable teachers and administrators to track their progress as they implement new alternatives, in order to change or revise interventions that are not working and to celebrate those that are. Finally, the school community needs transparency about both minor violations and those involving safety or resulting in arrests or referrals to law enforcement. To meet that need, the school and community need data that are publicly reported and disaggregated, including complete information about which groups are disciplined more than others, and for what types of offenses.

Collaboration with Community Agencies. No one agency can or should be expected to handle the needs of struggling students alone. Schools and school districts can form collaborative partnerships with mental health, probation, juvenile justice, and social service agencies, as well as business and union leaders, to help support teachers for students whose problems are severe.

Codes of Conduct That Support Alternative Strategies. School districts across the nation, from Denver to Chicago to Baltimore to Indianapolis, have restructured their codes of conduct, replacing simple lists of behaviors that lead to suspension and expulsion with comprehensive plans for creating positive school climates. By shifting the focus from punishment to prevention, and providing guidance for alternate strategies, such codes support and encourage teachers who are already seeking to implement strategies for supporting positive student behavior in the classroom.

Helping Parents Understand and Support Less Punitive Approaches. Parents and community members are often mixed in their support of zero-tolerance and exclusionary measures.64 In the face of school disruption, some parents and community members may see few options other than school removal, and they may support or even demand suspension or expulsion. On the other hand, the excessive use of punitive and exclusionary tactics often leads to pushback and resistance by community groups advocating for reform.65

Parent involvement is always critical, but never more so than in times of change. Effective reform of school discipline demands open lines of communication with parents and the community (including annual public reporting of data disaggregated by race, gender, and disability status) in order to emphasize the school community's commitment to safe and productive schools, and where needed, to provide evidence-based information that can reassure all stakeholders that new, more comprehensive systems are in fact more effective in meeting those goals.

Increased Presence of Mental Health and Instructional Support Personnel in Schools. Programs such as PBIS or restorative practices can improve the climate of schools overall, leading to reductions in rates of disruption, office discipline referral, and suspension. Yet, other support, in the form of the increased presence of mental health and instructional support personnel, is an invaluable addition to school climate improvement in any number of ways, including assistance in developing individualized behavior programs for challenging students, acting as a liaison with families, providing counseling services, and coordinating school-based and community-based programming for students and families.

We Can Get There from Here

Our nation's students deserve safe, productive, and positive school climates that promote teaching and learning for all children. The idea that a zero-tolerance philosophy based on punishment and exclusion could create effective learning climates has proven to be illusory. As the evidence of what does work has grown, strategies emphasizing relationship building, social-emotional learning, and structural change have emerged as promising paths to a comprehensive approach for developing positive school climates. Significant shifts in federal, state, and district policy are moving our nation toward the adoption of these more effective and evidence-based practices.

Yet it is critical that educators (including teachers, administrators, paraprofessionals, and other school staff) be fully supported through professional development, sufficient resources, and opportunities to collaborate, both among school professionals and with outside agencies. Together, these developments represent a fundamental sea change toward more effective and equitable school discipline, one that holds promise for reducing the loss of educational opportunity and increasing the likelihood of safe and healthy learning environments for all students.

Russell J. Skiba is a professor of counseling and educational psychology and directs the Equity Project at Indiana University. A member of the American Psychological Association's Task Force on Zero Tolerance and the lead author of its report, he has worked with schools across the country, directed numerous federal and state research grants, and written extensively about school violence, school discipline, classroom management, and educational equity. Daniel J. Losen is the director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the University of California, Los Angeles, an initiative at the Civil Rights Project. A former public school teacher, lawyer, and researcher, he has analyzed the trends in school discipline of nearly every school and district in the nation. This article draws upon the latest research on alternatives to punitive discipline and Losen's Closing the School Discipline Gap (Teachers College Press, 2015).

*PBIS is a framework for assisting school personnel in adopting evidence-based behavioral interventions to support positive academic and social behavior outcomes for all students. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. See especially, American Federation of Teachers, "Reclaiming the Promise: A New Path Forward on School Discipline Practices," accessed September 17, 2015, www.aft.org/position/school-discipline.

2. Russell J. Skiba and Reece L. Peterson, "The Dark Side of Zero Tolerance: Can Punishment Lead to Safe Schools?," Phi Delta Kappan 80, no. 5 (1999): 372–376, 381–382.

3. Russell J. Skiba and Kimberly Knesting, "Zero Tolerance, Zero Evidence: An Analysis of School Disciplinary Practice," in Zero Tolerance: Can Suspension and Expulsion Keep Schools Safe?, ed. Russell J. Skiba and Gil G. Noam, New Directions for Youth Development, no. 92 (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001), 17–43.

4. See, for example, Irwin A. Hyman and Donna C. Perone, "The Other Side of School Violence: Educator Policies and Practices That May Contribute to Student Misbehavior," Journal of School Psychology 36 (1998): 7–27.

5. Ronnie Casella, At Zero Tolerance: Punishment, Prevention, and School Violence (New York: Peter Lang, 2001); and Aaron Kupchik, Homeroom Security: School Discipline in the Age of Fear (New York: New York University Press, 2010).

6. John Devine, Maximum Security: The Culture of Violence in Inner-City Schools (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

7. Daniel J. Losen and Tia Elena Martinez, Out of School & Off Track: The Overuse of Suspensions in American Middle and High Schools (Los Angeles: Center for Civil Rights Remedies, 2013).

8. For a summary, see U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, "Data Snapshot: School Discipline," Civil Rights Data Collection, issue brief no. 1 (Washington, DC: Department of Education, 2014). The actual number of out-of-school suspension of 3.45 million represents 99 percent of responding public schools. The Office for Civil Rights reported that 1.9 million students were suspended just once and 1.55 million students were suspended more than once. A separate 130,000 students were expelled.

9. Daniel J. Losen, Cheri Hodson, Michael A. Keith II, et al., Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap? (Los Angeles: Center for Civil Rights Remedies, 2015). For comparison to the number of teachers, see "Number of Teachers in Elementary and Secondary Schools, and Instructional Staff in Postsecondary Degree-Granting Institutions, by Control of Institution: Selected Years, Fall 1970 through Fall 2021," in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2012, table 4.

10. Losen et al., Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?

11. Tracey L. Shollenberger, "Racial Disparities in School Suspension and Subsequent Outcomes: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth," in Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion, ed. Daniel J. Losen (New York: Teachers College Press, 2015), 31–43.

12. Losen et al., Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?

13. John M. Wallace Jr., Sara Goodkind, Cynthia M. Wallace, and Jerald G. Bachman, "Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Differences in School Discipline among U.S. High School Students: 1991–2005," Negro Educational Review 59 (2008): 47–62; and Shi-Chang Wu, William Pink, Robert Crain, and Oliver Moles, "Student Suspension: A Critical Reappraisal," Urban Review 14 (1982): 245–303.

14. Anne Gregory and Rhona S. Weinstein, "The Discipline Gap and African Americans: Defiance or Cooperation in the High School Classroom," Journal of School Psychology 46 (2008): 455–475; and Russell J. Skiba, Robert S. Michael, Abra Carroll Nardo, and Reece L. Peterson, "The Color of Discipline: Sources of Racial and Gender Disproportionality in School Punishment," Urban Review 34 (2002): 317–342.

15. Daniel J. Losen and Jonathan Gillespie, Opportunities Suspended: The Disparate Impact of Disciplinary Exclusion from School (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2012); and Russell J. Skiba, Robert H. Horner, Choong-Geun Chung, et al., "Race Is Not Neutral: A National Investigation of African American and Latino Disproportionality in School Discipline," School Psychology Review 40 (2011): 85–107.

16. Losen and Gillespie, Opportunities Suspended.

17. Robert Balfanz, Vaughn Byrnes, and Joanna Fox, "Sent Home and Put Off Track: The Antecedents, Disproportionalities, and Consequences of Being Suspended in the 9th Grade," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 17–30.

18. Ivory A. Toldson, Tyne McGee, and Brianna P. Lemmons, "Reducing Suspensions by Improving Academic Engagement among School-Age Black Males," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 107–117.

19. Jamilia J. Blake, Bettie Ray Butler, and Danielle Smith, "Challenging Middle-Class Notions of Femininity: The Cause of Black Females' Disproportionate Suspension Rates," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 75–88.

20. Kathryn E. W. Himmelstein and Hannah Brückner, "Criminal-Justice and School Sanctions against Nonheterosexual Youth: A National Longitudinal Study," Pediatrics 127 (2011): 49–57.

21. Sheila Heaviside, Cassandra Rowand, Catrina Williams, et al., Violence and Discipline Problems in U.S. Public Schools: 1996–97 (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 1998); and Matthew J. Mayer and Peter E. Leone, "A Structural Analysis of School Violence and Disruption: Implications for Creating Safer Schools," Education and Treatment of Children 22, no. 3 (1999): 333–356.

22. Hyman and Perone, "The Other Side of School Violence."

23. Jeremy D. Finn and Timothy J. Servoss, "Security Measures and Discipline in American High Schools," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 44–58.

24. David M. Osher, Jeffrey M. Poirier, G. Roger Jarjoura, and Russell C. Brown, "Avoid Quick Fixes: Lessons Learned from a Comprehensive Districtwide Approach to Improve Conditions for Learning," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 192–206.

25. Matthew P. Steinberg, Elaine Allensworth, and David W. Johnson, "What Conditions Support Safety in Urban Schools? The Influence of School Organizational Practices on Student and Teacher Reports of Safety in Chicago," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 118–131.

26. Steinberg, Allensworth, and Johnson, "What Conditions Support Safety in Urban Schools?"

27. Frank Bickel and Robert Qualls, "The Impact of School Climate on Suspension Rates in the Jefferson County Public Schools," Urban Review 12 (1980): 79–86; and Wallace et al., "Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Differences."

28. Erica Mattison and Mark S. Aber, "Closing the Achievement Gap: The Association of Racial Climate with Achievement and Behavioral Outcomes," American Journal of Community Psychology 40 (2007): 1–12.

29. Sheryl A. Hemphill, John W. Toumbourou, Todd I. Herrenkohl, et al., "The Effect of School Suspensions and Arrests on Subsequent Adolescent Antisocial Behavior in Australia and the United States," Journal of Adolescent Health 39 (2006): 736–744; and Linda M. Raffaele Mendez and Howard M. Knoff, "Who Gets Suspended from School and Why: A Demographic Analysis of Schools and Disciplinary Infractions in a Large School District," Education and Treatment of Children 26, no. 1 (2003): 30–51.

30. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, "Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools? An Evidentiary Review and Recommendations," American Psychologist 63 (2008): 852–862.

31. James Earl Davis and Will J. Jordan, "The Effects of School Context, Structure, and Experiences on African American Males in Middle and High School," Journal of Negro Education 63 (1994): 570–587; and M. Karega Rausch and Russell J. Skiba, "The Academic Cost of Discipline: The Relationship between Suspension/Expulsion and School Achievement" (paper, annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, April 2005).

32. Emily Arcia, "Achievement and Enrollment Status of Suspended Students: Outcomes in a Large, Multicultural School District," Education and Urban Society 38 (2006): 359–369; Linda M. Raffaele Mendez, Howard M. Knoff, and John M. Ferron, "School Demographic Variables and Out-of-School Suspension Rates: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of a Large, Ethnically Diverse School District," Psychology in the Schools 39 (2002): 259–277; and Michael Rocque, "Office Discipline and Student Behavior: Does Race Matter?," American Journal of Education 116 (2010): 557–581.

33. Tary Tobin, George Sugai, and Geoff Colvin, "Patterns in Middle School Discipline Records," Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 4 (1996): 82–94.

34. Balfanz, Byrnes, and Fox, "Sent Home and Put Off Track"; Christine A. Christle, Kristine Jolivette, and C. Michael Nelson, "School Characteristics Related to High School Dropout Rates," Remedial and Special Education 28 (2007): 325–339; Raffaele Mendez and Knoff, "Who Gets Suspended"; and Suhyun Suh and Jingyo Suh, "Risk Factors and Levels of Risk for High School Dropouts," Professional School Counseling 10 (2007): 297–306.

35. Tony Fabelo, Michael D. Thompson, Martha Plotkin, et al., Breaking Schools' Rules: A Statewide Study of How School Discipline Relates to Students' Success and Juvenile Justice Involvement (New York: Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2011).

36. Russell J. Skiba, Mariella I. Arredondo, and Natasha T. Williams, "More Than a Metaphor: The Contribution of Exclusionary Discipline to a School-to-Prison Pipeline," Equity and Excellence in Education 47 (2014): 546–564.

37. Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap; and David M. Osher, George G. Bear, Jeffrey R. Sprague, and Walter Doyle, "How Can We Improve School Discipline?," Educational Researcher 39 (2010): 48–58.

38. Anne Gregory, Joseph P. Allen, Amori Yee Mikami, et al., "The Promise of Teacher Professional Development Program in Reducing Racial Disparity in Classroom Exclusionary Discipline," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 166–179.

39. Anne Gregory, Kathleen Clawson, Alycia Davis, and Jennifer Gerewitz, "The Promise of Restorative Practices to Transform Teacher-Student Relationships and Achieve Equity in School Discipline," Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation (forthcoming), published electronically November 4, 2014, doi:10.1080/10474412.2014.929950.

40. Thalia González, "Socializing Schools: Addressing Racial Disparities in Discipline through Restorative Justice," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 151–165.

41. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), Safe and Sound: An Educational Leader's Guide to Evidence-Based Social and Emotional Learning Programs (Chicago: CASEL, 2003); and John Payton, Roger P. Weissberg, and Joseph A. Durlak, et al., The Positive Impact of Social and Emotional Learning for Kindergarten to Eighth-Grade Students: Findings from Three Scientific Reviews (Chicago: CASEL, 2008).

42. CASEL, Safe and Sound; and Joseph E. Zins, "Examining Opportunities and Challenges for School-Based Prevention and Promotion: Social and Emotional Learning as an Exemplar," Journal of Primary Prevention 21 (2001): 441–446.

43. Osher et al., "Avoid Quick Fixes."

44. Claudia G. Vincent, Jeffrey R. Sprague, CHiXapkaid (Michael Pavel), et al., "Effectiveness of Schoolwide Positive Interventions and Supports in Reducing Racially Inequitable Disciplinary Exclusion," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 207–221.

45. Sarah E. Pinkelman, Kent McIntosh, Caitlin K. Rasplica, et al., "Perceived Enablers and Barriers Related to Sustainability of School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports," Behavioral Disorders 40, no. 3 (2015): 171–183.

46. Dewey Cornell and Peter Lovegrove, "Student Threat Assessment as a Method of Reducing Student Suspensions," in Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap, 180–191.

47. Pamela Fenning, Therese Pigott, Elizabeth Engler, et al., "A Mixed Methods Approach Examining Disproportionality in School Discipline" (paper, Closing the School Discipline Gap Conference, Washington, DC, January 2013).

48. "Back to School Means Big Changes, Challenges at LAUSD," Los Angeles Daily News, August 11, 2013.

49. Lizette Alvarez, "Seeing the Toll, Schools Revise Zero Tolerance," New York Times, December 3, 2013.

50. Prudence Carter, Russell Skiba, Mariella Arredondo, and Mica Pollock, You Can't Fix What You Don't Look At: Acknowledging Race in Addressing Racial Discipline Disparities, Discipline Disparities Briefing Paper Series (Bloomington, IN: Equity Project at Indiana University, 2014); Anne Gregory, James Bell, and Mica Pollock, How Educators Can Eradicate Disparities in School Discipline: A Briefing Paper on School-Based Interventions, Discipline Disparities Briefing Paper Series (Bloomington, IN: Equity Project at Indiana University, 2014); Daniel J. Losen, Damon Hewitt, and Ivory Toldson, Eliminating Excessive and Unfair Exclusionary Discipline in Schools: Policy Recommendations for Reducing Disparities, Discipline Disparities Briefing Paper Series (Bloomington, IN: Equity Project at Indiana University, 2014); and Russell J. Skiba, Mariella I. Arredondo, and M. Karega Rausch, New and Developing Research on Disparities in Discipline, Discipline Disparities Briefing Paper Series (Bloomington, IN: Equity Project at Indiana University, 2014).

51. Losen, Closing the School Discipline Gap.

52. Gregory, Bell, and Pollock, How Educators Can Eradicate Disparities in School Discipline.

53. Hugh Mehan, In the Front Door: Creating a College-Bound Culture of Learning (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2012).

54. Jason A. Okonofua and Jennifer L. Eberhardt, "Two Strikes: Race and the Disciplining of Young Students," Psychological Science 26 (2015): 617–624.

55. Gregory et al., "Promise of Teacher Professional Development."

56. Gregory, Bell, and Pollock, How Educators Can Eradicate Disparities.

57. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, "Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools?"; and American Academy of Pediatrics, "Policy Statement: Out-of-School Suspension and Expulsion," Pediatrics 131, no. 3 (2013): e1000–e1007.

58. Fabelo et al., Breaking Schools' Rules.

59. "Key Policy Letters from the Education Secretary and Deputy Secretary," U.S. Department of Education, January 8, 2014, www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/guid/secletter/140108.html.

60. Losen et al., Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?

61. American Federation of Teachers, "A New Path Forward on School Discipline Practices."

62. National Education Association, "NEA and Partners Ramping Up Efforts to End School Discipline Disparities," news release, March 20, 2014, www.nea.org/home/58464.htm.

63. Greta Colombi and David Osher, Advancing School Discipline Reform, Education Leaders Report, vol. 1, no. 2 (Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Boards of Education, 2015).

64. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, "Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools?"

65. Padres & Jóvenes Unidos and Advancement Project, Lessons in Racial Justice and Movement Building: Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline in Colorado and Nationally (Denver: Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, 2014).

[illustrations by Daniel Baxter]