Much of my career as a researcher, writer, and teacher has been built on the idea that evidence should inform public policy. What works, why, and for whom? This was the view with which I leapt, as a young scholar, at the chance to join large research projects concerning the extraordinarily controversial issue of school vouchers: programs that use tax dollars to fund private school tuition and expenses. I felt lucky to work on a federally supported grant with the express purpose of training young analysts to use evidence-based research, while also joining a team that would examine Milwaukee’s famous voucher system.

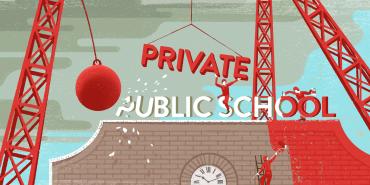

Looking back two decades later, I think that my youthful enthusiasm for evidence use in public policy seems misplaced—optimistic, for sure, and probably naïve. For in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the largest academic declines ever apparent in the education research record, on any topic, have been attributable to school vouchers. And yet the drumbeat to devote more and more resources to these voucher systems remains louder than ever.

The facts, it would seem, are no match for big-dollar investments—many of them opaque contributions from extraordinarily wealthy individuals who have been pushing voucher plans forward for more than 30 years. Voucher programs are expanding, while the evidence against them is mounting.

My contribution with The Privateers (see the sidebar here) is to highlight the way that vast wealth, virulent ideology—usually Christian nationalist in nature, but also a powerful strand of economic libertarianism—and an insular network of intellectuals, lawyers, and lobbyists have advanced an agenda from the rightward fringes of education policy into the political median.

Vast sums of money have supported the academic and other research-focused adherents to voucher ideology. That support—what amounts to industry funding of research to support a product—has successfully countered the empirical reality of the voucher scheme in many places. But those dollars have not been able to change that basic reality.

Here is that evidence in seven straightforward results:

1. Today’s Voucher Programs Primarily Support Students Who Were Never in Public School

As the number of states with vouchers grew in the years leading up to this book’s publication in 2024, the typical voucher recipient had never been in public school. They were already enrolled in private school without taxpayer support, were in homeschool, or were enrolling in private kindergarten from the start. Estimates uncannily hover around the same figure—roughly 70 percent—of students in the most recent programs coming from private schools in states that have released the data: Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Wisconsin.1 And we know from similar reporting that many of the private schools serving such students raise tuition once vouchers become law.2

2. The Larger and More Recent the Voucher Program Is, the Worse the Academic Results

Between 1996 and 2002, a series of academic papers and other reports by one team of pro-voucher researchers showed small positive voucher impacts on standardized tests. Between 2005 and 2010, two major evaluations—one in Milwaukee and the other in Washington, DC—found no impacts, whether positive or negative, on student outcomes. Since 2013, as voucher programs nevertheless began to expand, studies from multiple evaluation teams have found that vouchers cause some of the largest academic declines on record in education research. In Louisiana, for example, the results from studies modeled as randomized control trials—conducted by two separate research teams—found negative academic impacts as high as –0.40 of a standard deviation.3 A second, federal evaluation in Washington, DC, using that randomized design, and research in Indiana using statistical methods to measure student outcomes over time, both found impacts closer to –0.15 of a standard deviation.4 Results in Ohio using similar methods to the Indiana research found academic loss up to –0.50 of a standard deviation.5 To put these recent, negative impacts in perspective, current estimates of COVID-19’s impact on academic trajectories hover around –0.25 of a standard deviation, while Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans students was roughly –0.17 of a standard deviation.6

Similarly, although earlier studies—including one for which I was the lead author—found evidence that vouchers may modestly improve educational attainment (high school completion or college enrollment), more recent research has found no attainment impacts in either direction.7 Moreover, the mechanism behind any improvement is ambiguous, especially in the face of substantially negative test score results. If a small voucher advantage is apparent, it may be due to pipeline impacts—religiously affiliated high schools sending students to religiously affiliated colleges nearby. And research is clear that the attainment advantage exists primarily for students who don’t leave voucher programs—a major source of potential selection bias in even the randomized studies.8

3. Financially Distressed Private Schools Explain Negative Student Results

Research shows that vouchers create new markets for pop-up school providers, opening specifically to cash in on the taxpayer subsidy.9 The schools that existed before—if they accept vouchers at all—tend to be financially distressed, with the voucher program acting as something of a bailout.10 Research from Milwaukee, on the country’s oldest program, has shown that 41 percent of private schools accepting vouchers closed during the program’s life span.11 The average time to failure was four years for pop-up schools opening after that program expanded and eight years for preexisting schools. Financial distress is one reason that academic research predicted what media reporting has shown in newer voucher programs: that private schools raise their tuition when taxpayers begin subsidizing costs via vouchers.12

4. The Most Vulnerable Kids Suffer High Voucher Turnover—Or Are Pushed Out of Voucher Schools

When it comes to vouchers, the decision is as much about the school’s choice as parental choice. Much of the early debate on school vouchers—and about school choice more generally—concerned the concept of “cream-skimming.” The idea behind that unfortunate phrase was that private schools had incentives to admit relatively advantaged students over disadvantaged peers. Research on early programs that had limits on income to be eligible for a voucher found little to suggest that cream-skimming fears played out—at least insofar as they related to family resources.13 Instead, the evidence shows high rates of student turnover within and between school years for voucher-using children. In two studies, my own research team found not only that rates of student exit from Milwaukee’s voucher program approached 20 percent annually but that those former voucher students saw academic improvements once they returned to public schools.14 Who were those children who gave up their voucher? They tended to be students of color, lower-income students, and those with relatively low test scores.15 Reports from Florida, Indiana, and Louisiana have found similarly high annual exit rates.16 Investigative reporting has also identified student pushout as one way that voucher schools manipulate their enrollment to get the students they want. Reports show that students with disabilities and students who identify (or whose parents identify) as LGBTQ+ have been asked to leave voucher programs after a more transparent admissions process has let them into the school.17

5. Oversight Improves Voucher Performance

Since the dismal voucher results began appearing more than a decade ago, a major talking point among voucher advocates has been attributing that academic harm to “overregulation.”18 The idea largely concedes that, in past programs, voucher-accepting private schools were financially distressed, lower-quality providers. But that concession holds that government oversight on issues like admissions standards (which include enrollment rules against discrimination) or standardized testing kept out more effective providers. The problem with the “overregulation” theory is that it’s untested. In fact, to this day, the only empirical evidence of the effects of accountability on a voucher program comes from our team in Milwaukee, which found that, once a new law requiring No Child Left Behind–style performance reporting applied to the voucher program—and once private school outcomes were listed by school name, as in the public sector—voucher academic outcomes rose dramatically.19 It is partly through oversight policies like Wisconsin’s that we have some explanation for negative voucher impacts: there, for example, many of the lowest-scoring students in STEM subjects on the state exam were using vouchers to attend schools teaching creationism as their science curriculum.20

6. Parents Looking for Academic Quality Struggle to Find Room in Private Schools

The pattern of academic loss for voucher students raises the question of what parents actually want. Studies from New Orleans are especially useful, because researchers at and affiliated with Tulane University have been able to use school application data to study how parents make priorities.21 Those results indicate that, although parents do consider school features like demographics, safety, size, and distance to home, the academic performance of the school remains a determining factor in the way they rank preferences.22 Similar results have been found in Washington, DC, as well.23 Unfortunately, that evidence also suggests that there simply are not enough effective private schools to go around—perhaps a more practical explanation for dismal voucher results than ideological arguments about regulation.24

7. Voucher-Induced Competition Raises Public School Outcomes Somewhat—But the Evidence for Directly Funding Vulnerable Public Schools Is Stronger

Finally, for those hoping for a bright side to vouchers, there is modest evidence that voucher programs compel small improvements in public school achievement outcomes through competitive pressures. Such results have been found in Louisiana and Florida.25 In these papers, statistically significant impacts of competitive pressure are most apparent in low-income communities that stand to lose substantial funding from voucher programs. However, if the goal is to simply improve public school outcomes, studies showing the impact of directly funding public schools are far more prevalent.26 Providing more resources to begin with helps students more than pitting vulnerable communities against each other to compete for scarce dollars.

Looking Ahead

What would it mean to offer an evidence-based but also equity-based and ethical alternative to the deceptive simplicity of parents’ rights and private school choice as a cure-all? Any suggestion I have would draw from the old adage “You get what you pay for,” and from the Gospel of Matthew: Where our treasure is, there our hearts will be also.

Fund public schools. It really is that simple. In as much as the last decade of rigorous evidence on school vouchers has identified some of the largest academic losses in the research record, the last decade has also solidified a growing consensus among experts that the more money we spend on schools, the better off children are, not simply academically, but in later-life outcomes like higher wages and fewer encounters with the criminal justice system.

In the last several years, study after study takes that conclusion further. Academic outcomes improve dramatically.27 Educational attainment levels rise.28 Later-in-life incomes grow for workers who were children when policymakers decided to spend new dollars on their public schools.29 Poverty levels fall, and the chances that those children will commit future crimes and become incarcerated fall with them.30 When states take on the task of spending equalization across local districts, intergenerational economic mobility improves.31 And we know that when school spending declines—as in an economic recession—the results are equally apparent in the opposite direction: cuts to public school funding stall academic progress.32 That means that even the best-case scenario for school voucher impacts—evidence that vouchers will spur improvement when public and private schools compete for scarce financial resources—is in the long run a failed strategy for educational opportunity.33 And not all dollars are created equal: intergenerational mobility depends on states leveling the playing field for districts with different access to resources.34 That means that voucher plans that move state funds into private schools and leave public districts with only a local funding base—even if that base is secure in the short run—are setting those communities up for disaster when inevitable economic downturns come.

Of course, how we spend that money still matters, both in terms of the specific funding sources and the programs and services that money supports. Other books can and do detail evidence-based spending targets.35 But my view is from a big-picture perspective, and from the standpoint of motivating renewed investments not only in the operation of public education but in its purpose. And from that vantage point, answers must form around whole-child approaches, the idea of schools as communities, and the idea of learning as a lifelong endeavor. Ideas include universal school meals that nourish kids throughout the day and alleviate the stigma of poverty; school-based health clinics not simply for children but for the adults who serve them; weighted-funding formulas that reflect the true cost of educating diverse learners; grow-your-own teacher training programs drawing on local talent; and early childhood investments alongside after-school and summer school programs that recognize education is no longer just 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., Monday through Friday, 180 days a year. Each of these has a stronger base of evidence than school vouchers. And each in its own way provides a rationale for public education that affects daily life.

Then, because of who and what Christian nationalists are attacking (both implicitly and increasingly explicitly) when they speak about “education freedom,” there does require a direct defense of public education as a matter of human rights. The marginalization of LGBTQ+ families, reproductive rights, environmental justice, and histories of underserved communities in the United States not only coincides with but is a weapon in the attack on public schools. Our national debates on these issues are potent because they measure commitments to future generations of Americans who will define their own identities and their own destinies rather than having their parents and grandparents define their futures for them.

Josh Cowen is a professor of education policy at Michigan State University and, for the 2024–25 academic year, a senior fellow at the Education Law Center. Over the last two years, Cowen has written, testified, and spoken widely on the harmful effects of voucher programs. His work has appeared in outlets like the Brookings Institution Chalkboard, Time, The Hechinger Report, The Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, and The Philadelphia Inquirer. This article was excerpted with permission from The Privateers: How Billionaires Created a Culture War and Sold School Vouchers by Josh Cowen, September 2024, published by Harvard Education Press. See The Privateers for notes on Cowen’s funding sources throughout his career. The Privateers received no financial support from the AFT or any other organization apart from a six-month sabbatical granted by Michigan State University. For more information, please visit go.aft.org/p64.

Endnotes

1. See M. Lieberman, “Most Students Getting New School Choice Funds Aren’t Ditching Public Schools,” Education Week, October 4, 2023, edweek.org/policy-politics/most-students-getting-new-school-choice-funds-arent-ditching-public-schools/2023/10; G. Gomez, “Private School Students Flock to Expanded School Voucher Program,” Arizona Mirror, September 1, 2022, azmirror.com/2022/09/01/private-school-students-flock-to-expanded-school-voucher-program; D. Prieur, “Florida Policy Institute Asked for School Voucher Data. Here’s What Step Up for Students Provided,” Central Florida Public Media, September 14, 2023, wmfe.org/education/2023-09-14/florida-policy-institute-school-voucher-data-step-up-for-students; T. Richman and A. Morris, “Who Would Texas’ ESAs Benefit? Tension Emerges Over Who Would Get Money for Private School,” Dallas Morning News, March 24, 2023, dallasnews.com/news/education/2023/03/24/who-would-texas-education-savings-accounts-be-for-a-divide-over-homeschoolers-emerges/?outputType=amp; R. Opsahl, “More Than 29,000 Apply for Iowa Private-School Funds in First Year,” Iowa Capital Dispatch, July 6, 2023, iowacapitaldispatch.com/2023/07/06/more-than-29000-apply-for-iowa-private-school-funds-in-first-year; B. Bernhard, “Missouri Lawmakers Look to Expand Tax-Credit Voucher Program Mostly Serving Religious Schools,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15, 2023, stltoday.com/news/local/education/missouri-lawmakers-look-to-expand-tax-credit-voucher-program-mostly-serving-religious-schools/article_ef0b7afb-6805-586b-a668-67b2d10ecd64.html; E. Dewitt, “Most Education Freedom Account Recipients Not Leaving Public Schools, Department Says,” New Hampshire Bulletin, March 28, 2022, newhampshirebulletin.com/briefs/most-education-freedom-account-recipients-not-leaving-public-schools-department-says; S. Buduson and M. Ackerman, “The Cost of Choice: Most Students Who Benefit from Ohio EdChoice Vouchers Have Always Attended Private School,” ABC News 5 Cleveland, January 30, 2020, news5cleveland.com/news/local-news/investigations/the-cost-of-choice-most-students-who-benefit-from-ohio-edchoice-vouchers-have-always-attended-private-school; and E. Mendez, “75% of State Voucher Program Applicants Already Attend Private School,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 20, 2014, archive.jsonline.com/news/education/75-of-state-voucher-program-applicants-already-attend-private-school-b99274333z1-259980701.html.

2. T. Rushing, “Kim Reynolds’ Private School Voucher Plan Led to Tuition Hikes,” Iowa Starting Line, May 12, 2023, iowastartingline.com/2023/05/12/kim-reynolds-private-school-voucher-plan-led-to-tuition-hikes; and J. Solochek, “Florida’s New Voucher Law Allows Private Schools to Boost Revenue,” Tampa Bay Times, June 2, 2023, tampabay.com/news/education/2023/05/30/floridas-new-voucher-law-allows-private-schools-boost-revenue.

3. See A. Abdulkadiroğlu, P. Pathak, and C. Walters, “Free to Choose: Can School Choice Reduce Student Achievement?,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, no. 1 (2018): 175–206; and J. Mills and P. Wolf, “Vouchers in the Bayou: The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement After 2 Years,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 39, no. 3 (2017): 464–84.

4. M. Dynarski et al., Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts After One Year (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education, 2017, ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20174022/pdf/20174022.pdf; M. Dynarski and A. Nichols, “More Findings About School Vouchers and Test Scores, and They Are Still Negative,” Brookings Institution, July 13, 2017, brookings.edu/articles/more-findings-about-school-vouchers-and-test-scores-and-they-are-still-negative; R. Waddington and M. Berends, “Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement Effects for Students in Upper Elementary and Middle School,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37, no. 4 (2018): 783–808; and M. Berends and R. Waddington, “School Choice in Indianapolis: Effects of Charter, Magnet, Private, and Traditional Public Schools,” Education Finance and Policy 13, no. 2 (2018): 227–55.

5. D. Figlio and K. Karbownik, Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, Competition, and Performance Effects (Thomas B. Fordham Institute, July 2016), fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/research/evaluation-ohios-edchoice-scholarship-program-selection-competition-and-performance.

6. M. Kuhfeld et al., “The Pandemic Has Had Devastating Impacts on Learning. What Will It Take to Help Students Catch Up?,” Brookings Institution, March 3, 2022, brookings.edu/articles/the-pandemic-has-had-devastating-impacts-on-learning-what-will-it-take-to-help-students-catch-up.

7. J. Cowen et al., “School Vouchers and Student Attainment: Evidence from a State-Mandated Study of Milwaukee’s Parental Choice Program,” Policy Studies Journal 41, no. 1 (2013): 147–68; P. Wolf et al., “School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32, no. 2 (2013): 246–70; M. Chingos and B. Kisida, “School Vouchers and College Enrollment: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 45, no. 3 (2023): 422–36; and H. Erickson, J. Mills, and P. Wolf, “The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on Student Achievement and College Entrance,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 14, no. 4 (2021): 861–99.

8. J. Cowen, “‘Apples to Outcomes?’ Revisiting the Achievement v. Attainment Differences in School Voucher Studies,” Brookings Institution, September 1, 2022, brookings.edu/articles/apples-to-outcomes-revisiting-the-achievement-v-attainment-differences-in-school-voucher-studies.

9. M. Ford and F. Andersson, “Determinants of Organizational Failure in the Milwaukee School Voucher Program,” Policy Studies Journal 47, no. 4 (2019): 1048–68.

10. Y. Sude, C. DeAngelis, and P. Wolf, Supplying Choice: An Analysis of School Participation in Voucher Programs in DC, Indiana, and Louisiana (New Orleans: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, June 2017), educationresearchalliancenola.org/files/publications/Sude-DeAngelis-Wolf-Supplying-Choice.pdf.

11. M. Ford, “Funding Impermanence: Quantifying the Public Funds Sent to Closed Schools in the Nation’s First Urban School Voucher Program,” Public Administration Quarterly 40, no. 4 (2016): 882–912; and Ford and Andersson, “Determinants of Organizational Failure.”

12. D. Hungerman and K. Rinz, “Where Does Voucher Funding Go? How Large-Scale Subsidy Programs Affect Private-School Revenue, Enrollment, and Prices,” Journal of Public Economics 136 (2016): 62–85; and N. Morton, “Arizona Gave Families Public Money for Private Schools. Then Private Schools Raised Tuition,” Hechinger Report, November 27, 2023, hechingerreport.org/arizona-gave-families-public-money-for-private-schools-then-private-schools-raised-tuition.

13. R. Waddington, R. Zimmer, and M. Berends, “Cream Skimming and Pushout of Students Participating in a Statewide Private School Voucher Program,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (2023): 01623737231183397.

14. J. Cowen et al., “Going Public: Who Leaves a Large, Longstanding, and Widely Available Urban Voucher Program?,” American Educational Research Journal 49, no. 2 (2012): 231–56; and D. Carlson, J. Cowen, and D. Fleming, “Life After Vouchers: What Happens to Students Who Leave Private Schools for the Traditional Public Sector?,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 35, no. 2 (2013): 179–99.

15. Erickson, Mills, and Wolf, “The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship”; Waddington, Zimmer, and Berends, “Cream Skimming and Pushout”; and D. Kuehn, M. Chingos, and A. Tilsley, “Most Students Receive a Florida Private School Choice Scholarship for Two Years or Fewer: What Does That Mean?,” Urban Institute, March 6, 2020, urban.org/urban-wire/most-students-receive-florida-private-school-choice-scholarship-two-years-or-fewer-what-does-mean.

16. Erickson, Mills, and Wolf, “The Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship”; and Kuehn, Chingos, and Tilsley, “Most Students Receive.”

17. P. Petrovic, “False Choice: Wisconsin Taxpayers Support Schools That Can Discriminate,” Wisconsin Watch, May 5, 2023, wisconsinwatch.org/2023/05/wisconsin-voucher-schools-discrimination-lgbtq-disabilities; and J. Donheiser, “Choice for Most: In Nation’s Largest Voucher Program, $16 Million Went to Schools with Anti-LGBT Policies,” Chalkbeat, August 10, 2017, chalkbeat.org/2017/8/10/21107318/choice-for-most-in-nation-s-largest-voucher-program-16-million-went-to-schools-with-anti-lgbt-polici.

18. J. Bedrick, “The Folly of Overregulating School Choice,” Education Next, January 5, 2016, educationnext.org/the-folly-of-overregulating-school-choice.

19. J. Witte et al., “High-Stakes Choice: Achievement and Accountability in the Nation’s Oldest Urban Voucher Program,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 36, no. 4 (2014): 437–56.

20. J. Cowen, “How Taxpayer-Funded Schools Teach Creationism—and Get Away with It,” New Republic, January 30, 2014.

21. National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice, “Our Mission & Work,” Tulane University, reachcentered.org/about.

22. J. Lincove, J. Cowen, and J. Imbrogno, “What’s in Your Portfolio? How Parents Rank Traditional Public, Private, and Charter Schools in Post-Katrina New Orleans’ Citywide System of School Choice,” Education Finance and Policy 13, no. 2 (2018): 194–226; and D. Harris and M. Larsen, “What Schools Do Families Want (and Why)? Evidence on Revealed Preferences from New Orleans,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 45, no. 3 (2023): 496–519.

23. S. Glazerman and D. Dotter, “Market Signals: Evidence on the Determinants and Consequences of School Choice from a Citywide Lottery,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 39, no. 4 (2017): 593–619.

24. J. Lincove, J. Valant, and J. Cowen, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want: Capacity Constraints in a Choice-Based School System,” Economics of Education Review 67 (2018): 94–109.

25. A. Egalite and J. Mills, “Competitive Impacts of Means-Tested Vouchers on Public School Performance: Evidence from Louisiana,” Education Finance and Policy 16, no. 1 (2021): 66–91; D. Figlio and C. Hart, “Competitive Effects of Means-Tested School Vouchers,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6, no. 1 (2014): 133–56; and C. Rouse et al., “Feeling the Florida Heat? How Low-Performing Schools Respond to Voucher and Accountability Pressure,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5, no. 2 (2013): 251–81.

26. C. Jackson and C. Mackevicius, “What Impacts Can We Expect from School Spending Policy? Evidence from Evaluations in the United States,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16, no. 1 (January 2024): 412–46; and M. Barnum, “4 New Studies Bolster the Case: More Money for Schools Helps Low-Income Students,” Chalkbeat, August 13, 2019, chalkbeat.org/2019/8/13/21055545/4-new-studies-bolster-the-case-more-money-for-schools-helps-low-income-students.

27. For an academic summary, see Jackson and Mackevicius, “What Impacts Can We Expect”; for comprehensive media coverage of these results, including links to papers and reports, see M. Barnum, “Does Money Matter for Schools? Why One Researcher Says the Question Is ‘Essentially Settled,’” Chalkbeat, December 17, 2018, chalkbeat.org/2018/12/17/21107775/does-money-matter-for-schools-why-one-researcher-says-the-question-is-essentially-settled; and Barnum, “4 New Studies.”

28. R. Johnson and C. Jackson, “Reducing Inequality Through Dynamic Complementarity: Evidence from Head Start and Public School Spending," American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11, no. 4 (2019): 310–49.

29. Johnson and Jackson, “Reducing Inequality.”

30. Johnson and Jackson, “Reducing Inequality”; E. Baron, J. Hyman, and B. Vasquez, “Public School Funding, School Quality, and Adult Crime,” National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper no. 29855, March 2022, nber.org/papers/w29855.

31. B. Biasi, “School Finance Equalization Increases Intergenerational Mobility,” Journal of Labor Economics 41, no. 1 (2023): 1–38.

32. C. Jackson, C. Wigger, and H. Xiong, “Do School Spending Cuts Matter? Evidence from the Great Recession,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13, no. 2 (2021): 304–35.

33. Figlio and Hart, “Competitive Effects.”

34. Biasi, “School Finance Equalization.”

35. See, for example, B. Baker, Educational Inequality and School Finance: Why Money Matters for America’s Students (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2021).

[Illustrations by Pep Montserrat]