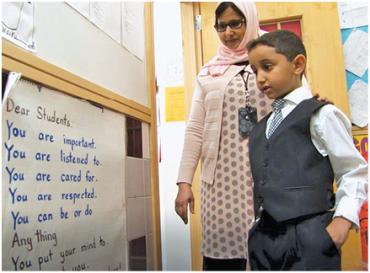

On the wall outside her first-grade classroom, teacher Welaya AlHaiki has posted a letter to her students. It reads:

Dear Students,

You are important.

You are listened to.

You are cared for.

You are respected.

You can be or do

Anything

You put your mind to.

I support you.

You are in a safe place!

Love,

Ms. AlHaiki

Many elementary school teachers post welcoming or reassuring messages outside their classroom doors. But for some of AlHaiki’s students, this message holds particular meaning.

As refugees from Yemen, a country torn apart by an ongoing civil war, many of these children have felt unsafe. In their homeland in recent years, many students were exposed to violence from the war as well as other hardships. At times, their schooling was interrupted.

Now the students are in a public school that many of them will soon consider a second home, where they will learn under the care and instruction of AlHaiki and her colleagues.

Their school, Salina Elementary, is in Dearborn, Michigan. In some ways, it’s fitting they are learning what it means to become American in an industrial city in the middle of America, the home of the Ford Motor Company. Long a haven for immigrants, Dearborn has welcomed its latest newcomers with overwhelming support. The success of this effort comes in part from a strong labor-management collaboration between Dearborn Public Schools and the local union, the Dearborn Federation of Teachers (DFT), which has enabled educators to meet students’ needs so that they can feel safe enough to learn.

Last year, the team at ColorinColorado.org, the nation’s leading website for educators and families of English language learners (ELLs), explored this collaboration in Dearborn. Through a partnership with the American Federation of Teachers and the DFT, we produced You Are Welcome Here, a 20-minute film about the Dearborn Public Schools’ comprehensive efforts on behalf of this resilient student population. Throughout the course of our school visits, numerous interviews, and two intensive days of filming, we began to develop a deeper understanding of what’s working in Dearborn and what other school districts can learn from its example.

The Salina Community

Salina Elementary School is located in the Southend neighborhood of Dearborn, which borders Detroit. More than 95 percent of the students are ELLs, with the vast majority coming from Yemen. Many of the students at Salina have older siblings who attend Salina Intermediate, the middle school across the street. At both schools, around 90 percent of the students receive free or reduced-price meals, an indicator of poverty.

In spite of the challenges facing many families, the hard work of both schools is paying off. Salina Elementary was recently nominated by the state’s Department of Education for a national award for Title I schools, recognizing its success with ELLs. And in 2018, Salina Intermediate, which had been struggling just a few years before, was nominated as a finalist for the same award.

The schools’ Southend neighborhood developed in the first half of the 20th century around a Ford automobile plant that would later become the company’s largest industrial complex worldwide. At one time, it employed more than 100,000 workers. Many were immigrants from Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America. “The Southend is iconic in the sense that it’s where every [immigrant] family started,” says Rose Aldubaily, the director of ELL services for Dearborn Public Schools and herself a native of the community. “Before it was Lebanese American, it was Polish American. And before it was Polish American, it was Italian American.” (Prior to filming our interview with her in the conference room of Salina Intermediate, Aldubaily noted that the room had once been her kindergarten classroom.)

In part because the Southend was isolated from the rest of the city—literally on the other side of the tracks—it was a strong, tight-knit community, and it remains so today. Alumni who attended the neighborhood schools still gather for reunions. “There was this sense of belonging that is hard to explain,” wrote one former student on a local news website. “The common ground we had was that everyone was looking for a better life, whether you were Lebanese, Italian, Polish, Puerto Rican, or Yemeni.”*

Today, Yemeni restaurants and shops line the small commercial strip in the heart of the neighborhood. The local mosque, the second built in the United States, now includes a school, library, and community center—proof the Yemeni community here has thrived.

Yet while many Yemeni immigrants historically have come to Dearborn in search of a better life, those who have come more recently are also fleeing a brutal civil war. Many of Salina’s students have experienced violence, hardship, and long separations from family members. Afrah Saleh, the English language development specialist at Salina Elementary (who herself came from Yemen as a child), notes that, in recent years, students have been arriving from Yemen with less and less schooling, as the situation there has deteriorated.

The impact of such trauma can be wrenching. Sue Stanley, Salina Elementary’s principal, recalls the arrival of one student in particular. “Any time there was a loud noise, this poor little kindergarten boy would just hit the floor and he would cry,” she says. “We had to go get his third-grade brother to come down … and put his body over this little boy to help calm him down, because where he came from, there were bombs.”

Rola Bazzi-Gates, one of the district’s special education coordinators and a social worker, has worked in the Salina community for many years. She has a special appreciation for what it takes to work through hardship, since she and her family left Beirut in the 1980s for America. “I grew up with war, and it was very hard,” she says. “So I know what it means to be without water, without electricity, and going to hide.”

Over the years, refugees from many global conflicts have settled in Dearborn. In the 1990s, Iraqi families came to the city during the Gulf War. Back then, Glenn Maleyko, a young third-grade teacher at Salina Elementary, found himself at a loss for how to respond when he saw a student’s disturbing drawings in a journal. It turned out the student had seen his uncle killed in Iraq.

Today, Maleyko is the superintendent of Dearborn Public Schools. His years as a classroom teacher at Salina inform his work as a district leader. “I couldn’t understand necessarily what the children or their families were going through,” he says. “The one thing I could do was provide them with the highest-quality education I could so that they could break that poverty or break some of the traumatic experiences that they had in the past [to help] future generations of families.”

To that end, the district continues to increase staff capacity around trauma-informed instruction† through training for teachers, administrators, support specialists, and mental health professionals. Topics in these trainings include the impacts of post-traumatic stress disorder, social-emotional health, and understanding mindfulness and meditation. “Before we can even begin to talk about academics, we have to make sure they’re emotionally OK,” says Saleh, “letting them know that they’re in a safe place and that they will thrive with us here.”

Educators are also learning how to make connections to students’ experiences through their training on trauma-informed practice and culturally responsive instruction. Anna Centi, who teaches language arts at Salina Intermediate, has found a good match for her students in the novel A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park, which tells the story of boys fleeing conflict in South Sudan. The discussions of long walks in the desert and no access to water spark personal memories from her students. It takes a teacher trained in trauma and cultural sensitivity to lead these conversations safely.

When Centi asks one of her students, Nabila, what it feels like to go without water, Nabila responds, “Like you’re gonna die.” It turns out that Nabila has lived this experience, as her family fled the bombings near her village. “When we went to the villages,” she says, “there’s no water. And they [are] selling some water, but it’s a lot of money. And it’s hard.”

In our film, Centi says, “I’m always looking to try to find something that the kids will identify well with, so they would be able to dig a little bit deeper, and you could make the curriculum a little bit more rigorous with something they connect that well with.” Asked what she thinks of A Long Walk to Water, Nabila responds, “I like the book. Ms. Centi picked the best book for us because we remember Yemen when we are in school.”

At Salina Elementary, the principal, social worker, and family liaison all work together to welcome students into the school and reassure families that their children are indeed safe. Adelah Saleh, a mother with students at the school, appreciates such reassurance. “The most important thing a child needs in his academic and everyday life is safety,” she says in Arabic. “In school, my kids feel safe, secure, [and] maintain mental stability. And that is what helps them most.”

The same collaboration around safety happens at Salina Intermediate, where Diana Alqadhi, the English language development specialist, knows firsthand the importance of building relationships with students. “If you build the connection with them, they don’t want to let you down, so they’ll work a little bit harder,” she says. “If you make that personal connection with those kids, then they know who to turn to when they need to turn to someone.”

The relationship with Alqadhi is making a difference for one of her students in particular, Hana, a middle schooler who has recently arrived from Yemen. She came here with her two brothers and without her mother. Asked how she was handling the separation, she responds in Arabic, as teacher Dalyia Muflahi translates for her in English: “When I was in Yemen, I lived a happy life because my mother was there, and everyone was there with me. Then, after I came here to America, I felt separated from them, and I lost hope. How can I say this? I felt lonely.”

Fortunately, Hana has since bonded with Alqadhi. In our film, You Are Welcome Here, she smiles when asked about her favorite things at school. “I love Mrs. Alqadhi,” she says. She pauses before continuing, “And I love eating pizza.”

Although the connection between this student and teacher seems natural, the district doesn’t leave it to chance. For one thing, throughout the district, the English language development specialists, who provide buildingwide support for ELLs, speak conversational Arabic (although not all teachers working with newcomer or ELL students are bilingual). Given the high number of Arabic speakers in the district, such a requirement makes sense. The district has also worked with the Dearborn Federation of Teachers to increase the number of classroom teachers with an ESL (English as a second language) credential, to make it easier for paraprofessionals to earn their teaching credentials, and to make it easier for administrators to make bilingual language skills (in Arabic and English) a hiring requirement where needed.

“We have to work toward solutions,” says Chris Sipperley, the former president of the DFT. “I learned very quickly in this position that we have various needs for our EL students. And within the last 10 years, those have only increased.”

Intensive Support

In the Salina community, Hana’s experience of family separation is not unique. Alqadhi notes that at least half of her middle school newcomers are here in the United States without their mothers. In many cases, mothers have stayed behind in Yemen or other Middle Eastern countries awaiting visas while children have joined their fathers or other relatives in Dearborn. Often, older siblings have numerous responsibilities at home, including the care of younger siblings.

Such was the case of brothers Hussein and Yussef Kady. Hussein, now in middle school, recalls answering his little brother’s repeated questions about when their mother would join them. “It’s hard for him,” he says. “And us, too.”

“I was mad because my mom was still [in] Yemen,” recalls Yussef, who came here in kindergarten and is now reading above grade level. “It wasn’t that fun, and I missed her. I cried all the time.”

Families who have made it to Dearborn may have also experienced long periods of hardship and uncertainty in Yemen and on their journey to the United States, including a lack of running water, food, and medical care, and extreme conditions—a situation common for many refugees.

Alqadhi recalls covering another teacher’s class of newcomer students one day when the students started talking about cattle rafts. As she asked them to tell her more, she realized that multiple students had had the same experience. The quiet class suddenly became animated as they explained that they had traveled 10 to 12 hours standing on these rafts among cattle as they fled from Yemen to Djibouti to escape the war.

To help students deal with all they’ve been through, special education coordinator Bazzi-Gates and her colleagues take a holistic approach. “We look at the whole child and not just, ‘Are they focusing in class, are they learning?’ By listening to them, observing them, asking questions, you’ll be able to know how to help them better.”

Dearborn’s Multi-Tiered Support System is designed to address students’ complex needs. It’s a robust process ensuring that ELL and bilingual educators, special educators, social workers, classroom teachers, administrators, and families are all part of the same conversation. The district also collaborates with local community agencies, such as ACCESS (the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services), to provide additional social-emotional support, including mental health training and services for both students and families around issues such as trauma, substance abuse, and suicide prevention. ACCESS also provides families with classes, job training, and school supplies, among other resources.

Once this intensive support has been established, it’s also important to give the students some time to adjust. “We just let them be for a little bit,” says Stanley, Salina Elementary’s principal. “They have to feel comfortable and secure and grounded for a while.”

Another way the schools build students’ confidence is hands-on learning. At Salina Elementary, this includes makerspace, an annual STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) fair, LEGO League, a dynamic arts program, and a school garden. Stanley notes that these kinds of activities are particularly important because they can help children start feeling successful even before beginning to learn English.

This was a lesson she says she learned firsthand after observing a kindergartner. “This little boy seemed sad for the longest time,” Stanley says. Thanks to a program the school brought in called “robot garage,” the student began to engage in his learning. “He had that robot put together before anybody gave him any directions,” she says. “The look on this child’s face really showed that we have to find ways to break the language barrier for kids, give them hands-on learning, do makerspace, do these kinds of things where you don’t need language first.”

In addition to engaging students, Bazzi-Gates says it is particularly important to establish trust with families early on so that they will be more open to recommendations from the school regarding support services, especially around confidential issues they may not wish to discuss with others. When visiting both Salina Elementary and Salina Intermediate, evidence of families’ comfort is in full force, from the hugs between staff members and parents, to the groups of mothers who emerge in the hallways after classes for parents, to the big crowds who attend special events.

Norieah Ahmed, one of Salina Elementary’s accounting secretaries, greets all school visitors with a radiant smile. Often, the families have been instructed to look for her specifically. “To be the first face that they see, I can immediately see some relief on their faces,” says Ahmed, whose family is Yemeni and who also speaks fluent Arabic. After months or even years of adversity and displacement, “they feel like they’re in a place that they belong, versus yet another strange place.”

Another key person in this effort is the family liaison, Sana Hamade, a native of Lebanon. “Leaving a country—you were born there, your roots are there—it’s not easy at all,” she says. “So when they come here, the minimum we can do … [is] give them this attention, this love, this care.”

On a practical level, developing partnerships with families includes translating all school communication, including letters and phone calls, into Arabic and other languages, such as Urdu, that families speak. Additional outreach initiatives include parent workshops, community meetings, a weekly coffee hour with the principal, home visits, classes, and special events for families to attend. Both schools are careful to respect cultural and religious norms, as well as families’ schedules.

School administrators work closely with family liaisons and front office staff to establish these partnerships. This is a critical step for educators who are not from the culture of the school’s families or who don’t know Arabic, the language that the majority of families speak. Stanley, Salina Elementary’s principal since 2013, admits that she has made some mistakes and had some misgivings when she first visited the neighborhood. “I really was concerned about the language being a barrier,” she says. “But I trusted the district when they gave me this position to know that we could overcome all of that. So it was a year of learning.”

What made a difference? “I talked less and listened more my first year,” she says, which helped tremendously.

Stanley also keeps her own family story in mind in her work with Salina families. “It’s the same opportunity that my grandparents wanted for my parents back in the 1920s,” she says. “They were coming over to give their children an education … [and] to make life better for everybody.”

Hamade, the family liaison, recalls that when Stanley came to the school, she had lots of questions, so Hamade took her on a tour of the neighborhood, showing her restaurants and other places where signs are posted in Arabic. This was the kind of tour that Superintendent Maleyko’s principal took him on when he was a new teacher at Salina in the 1990s. That trip included a visit to the local mosque. Soon, Maleyko, originally from Canada, was going on home visits. “One of the things I remember clearly is that the parents … were very appreciative of the work that you’re doing to educate their children.” It’s an appreciation that Salina teachers experience regularly. “In our culture, a teacher is extremely valued,” Alqadhi says. “We are held in high esteem. … They completely entrust us with their children.”

The Dearborn Federation of Teachers has also played a crucial part in supporting such school-family partnerships. In collaboration with the union, the district’s ELL department has provided professional development opportunities to teachers who are involved with the Parent Teacher Home Visits (PTHV) project.‡ This training was developed after receiving requests from union members who wanted to learn how to establish more effective partnerships with immigrant families.

According to Jane Mazza, president of the DFT (who got her start student teaching at Salina), the union has worked closely with the district since 2015 to ensure that the PTHV project has had funding in the school budget. The DFT has also held training classes and coordinated union members’ expansion of the PTHV into other district schools. And it has paid to send members for additional training at PTHV conferences. “We strongly feel that working together on this project helps our students,” Mazza says.

As for the home visits themselves, she explains that teachers ask families, “What are your hopes and dreams for your child?” Every culture can relate to this simple yet profound question. As a result, “We focus on building the relationship with the families so they understand we are trying to help them with this dream.”

“A Second Home”

It is not surprising that, throughout the filming of You Are Welcome Here, many of the students, staff members, and families we spoke with in the Salina community refer to their schools as another home. “We are a family,” says Jamel Lawera, the former principal of Salina Intermediate, whose own mother and other family members attended Salina.

Maleyko, the district superintendent, who previously served as principal of Salina Intermediate as well as a teacher, also shares the sentiment. “Salina is always going to be a part of who I am,” he says. “It’s tied to my heart as a person, as an educator, as a professional.”

As AlHaiki, the first-grade teacher whose words we began our story with, likes to remind her students, their teachers at Salina Elementary and Salina Intermediate—and throughout Dearborn—know they can be anything, and the students themselves have big dreams. Asked about their goals, Nabila says she wants to be a doctor, and Hussein says he wants to be a businessman. Hana at first is undecided between becoming a doctor and a teacher, but then decides she would prefer to be a teacher because she is afraid of needles. And Yussef? “I want to be a police officer,” he says, “but my dad said no. He wants me to be a doctor.”

Just as Mazza notes above, the families know that great things are possible for their children, too. It is that belief that has enabled them to overcome so much in search of a better future for their families. When asked about her hopes for her children, Adelah Saleh shares two, the first of which is fairly modest. She’d like to see them take more field trips in school—perhaps to a science museum or to the state capital, Lansing. But she also has something greater in mind. “I want them to be successful in life, to finish their education, and to spread peace,” she says in Arabic, as Hamade, the family liaison, translates into English. “We came from a country with no peace. This is what we miss, and this is what we wanted.”

Lydia Breiseth is the director of Colorín Colorado, where she manages content on ColorinColorado.org, multimedia production, outreach, and partnerships, including collaboration with its major partner, the American Federation of Teachers.

*“The Other Side of the Tracks: A Trip Down Memory Lane Living in the South End of Dearborn,” published September 17, 2012, is available at https://patch.com/michigan/dearborn/bp--the-other-side-of-the-tracks-936ea51a. (return to article)

†For more on trauma-informed instruction, see “Supporting Students with Adverse Childhood Experiences” in the Summer 2019 issue of American Educator, available at www.aft.org/ae/summer2019/murphey_sacks. (return to article)

*‡For more on the importance of home visits, see “Connecting with Students and Families through Home Visits” in the Fall 2015 issue of American Educator, available at www.aft.org/ae/fall2015/faber. (return to article)

[Photos courtesy of the author and Colorín Colorado]