The large numbers of teachers and families of children in public schools participating in a movement to opt out of high-stakes, standardized testing indicate strong resistance to a school “reform” that has done little to improve public education and much to undermine it.

Bipartisan legislation allowing parents to “opt out” is currently being debated in many state legislatures. Feeling the pressure of parents, educators, and community members, politicians and policymakers have slowly begun to respond to the collateral damage generated by high-stakes testing, which has resulted in public school closures, as well as demoralized students and teachers. Suddenly, testing has become a major issue in local elections.

Last year, the American Statistical Association released a statement criticizing the use of value-added measures (VAM) in teacher evaluation. VAM purports to show the contribution of individual teachers by comparing their students’ current test scores with the scores of those same students in previous school years, as well as with the scores of other students in the same grade, so that administrators can isolate the contribution, or “value added,” that each teacher provides in a given year. The American Statistical Association argued that value-added measures based on standardized tests “do not directly measure potential teacher contributions toward other student outcomes.”1

The American Educational Research Association has also cautioned against the use of VAM in teacher evaluation.2 Even the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a major proponent of VAM, has backed off its initial support.3

In California, Governor Jerry Brown recently signed legislation suspending standardized exit exams the state required high school seniors to pass in order to graduate. So distrustful was Brown of the tests’ value that he made the law retroactive to 2004, thus allowing students who had met all other graduation requirements to receive their diplomas.4

In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo has also dialed back the emphasis on high-stakes testing. Cuomo and the legislature had approved a teacher evaluation system in which up to 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation was based on student standardized test scores. But in December 2015, a task force created by the governor to review the Common Core State Standards and their alignment to standardized tests recommended that such tests no longer be used to evaluate teacher and student performance. The governor has embraced the recommendations of the task force, whose members include Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers.5

Perhaps most significant of all, last spring half a million parents across the country opted their children out of their annual standardized state tests.6

The pushback has not been confined to the states. In fall 2015, it reached the federal level when then–Secretary of Education Arne Duncan called for a cap on standardized tests and recommended that no student spend more than 2 percent of instructional time taking them. “At the federal, state, and local level, we have supported policies that have contributed to the problem in implementation,” he noted. “We can and will work with states, districts, and educators to help solve it.”7

A few months after Duncan’s statement, President Obama signed into law the Every Student Succeeds Act, which reauthorizes the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, formerly known as No Child Left Behind. One of the hallmarks of the law is that it prohibits the federal government from mandating or prescribing the terms of teacher evaluation. And it stipulates that the giving of federal funds to schools can no longer be conditioned on using student test scores in teacher evaluation. Just as important, the law permits several states to develop and implement assessment systems that allow for performance-based assessments in lieu of traditional standardized tests.

While there are conditions and limits, states now have an opportunity to reshape their assessment and accountability systems, which in turn could lead to more fundamental changes in public education as a whole. We encourage them to consider implementing performance-based assessment. Given that the tide is turning away from testing for accountability purposes, a time-honored approach that has worked for students and teachers in New York deserves a second look.

How We Can Do Better

For more than two decades, the New York Performance Standards Consortium has offered a viable option to preparing students for college and career. The Consortium’s approach relies on performance-based assessments, which include essays, research papers, science experiments, and high-level mathematical problems that have real-world applications. Instead of superficially assessing what students know and can do on a bubble test, performance-based assessments measure a student’s knowledge and skills in a deep and meaningful way over time.

Just as important, they promote student and teacher ownership, essential to student engagement. Answering someone else’s questions about historical events, literary genres, scientific facts, or mathematical procedures is not nearly as effective as students generating and answering their own questions, making decisions, finding their voice, and handling ambiguity.

The Consortium, a coalition of nearly 40 public high schools, has shown that acquiring academic knowledge and skills requires helping students engage with the power of ideas. The Consortium schools rely on a constructive assessment system that grows out of curriculum, respects teachers as the professionals they are, and initiates collaborative projects with other groups of teachers and schools as opposed to the competitive structures set up by past federal education policies such as No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top.

In Consortium schools, curriculum drives assessment, as it should. When it’s the other way around, the result is that test prep too often dominates instruction. Fortunately, Consortium schools have steered clear of this misguided practice because they view assessment as an extension of the learning process, not as a punitive bludgeon.

The Consortium’s story began in 1992, when then–New York State Education Commissioner Thomas Sobol recognized the accomplishments of 28 small New York City public high schools. He designated these schools Compact for Learning schools and directed the New York State Education Department to draw on their expertise to help other schools that were struggling.8

Impressed with the way these schools assessed their students, Sobol granted them a waiver from most of the state’s Regents exams (standardized tests in core high school subjects) required for graduation.9 Drawing on the work of distinguished educators such as Vito Perrone, Ted Sizer, and Deborah Meier,* these schools had created successful learning environments that engaged diverse groups of students and promoted inquiry-based teaching and learning.

By 1998, however, standards-driven assessment began to dominate the educational landscape with new tests and demands for new standards. Sobol had moved on, and the new commissioner, Richard Mills, along with an assertive New York State Board of Regents, adopted a one-size-fits-all approach to curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Only the state’s private school association, the New York State Association of Independent Schools, and some of the Compact for Learning schools received a waiver to remain outside this mandate.

Responding to this changing education landscape, the public schools formed the New York Performance Standards Consortium and reached out to the United Federation of Teachers, as well as the parent community and other political allies, to gain support. The move led to a direct confrontation with Mills and his allies in the state Department of Education.

When it looked like the waiver might be withdrawn, more than 1,500 parents, teachers, and students belonging to the Consortium took their case to the board of regents and state legislators. Consortium advocates argued for flexibility in ascertaining students’ educational achievement through performance-based assessments and promoted the idea that the Consortium’s approach produced better results.10

While not suggesting that every school adopt its system, the Consortium asked why the department did not want its schools to continue to flourish. To maintain the waiver, the Consortium focused on making public the results of the department’s test-driven approach to assessment alongside the Consortium’s model, which was equal to or better than existing educational approaches. Ultimately, student achievement in Consortium schools was favorably measured in terms of student demographics, school climate, and teacher retention, as well as student dropout and graduation rates.

Through a prolonged campaign that involved litigation, lobbying, mass protest, and media persuasion, the Consortium protected the waiver and Mills’s efforts to rescind it were unsuccessful.

A Look at Performance Assessments

Today, the Consortium includes 38 New York public high schools that use performance assessments in lieu of four out of the five Regents exams mandated for the state’s high school graduates (students still take the Regents exam in English language arts). The 36 schools that are located in New York City are grouped together under their own superintendent. Two other schools are located in Rochester and Ithaca, and they report to their local superintendents.

The Consortium continues to support a teacher-designed, student-focused, and externally reviewed assessment system that provides a fuller and deeper measure of student achievement than standardized testing.

In building and sustaining its approach, Consortium educators understand what subsequent years of headlines and published standardized test results have failed to acknowledge: a crucial link exists among assessment, curriculum, and teaching. High-stakes, test-driven assessment inhibits collaboration among educators, hinders student engagement, and undermines critical thinking.

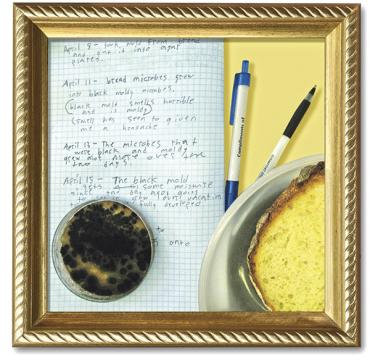

The Consortium’s approach is based on the idea that because learning is complex, assessment should be too. In other words, if schools are to challenge students to think critically, explain their work, and pose and consider questions that involve complex responses, it follows that students should be required to demonstrate in a systematic way what they know and can do with the knowledge and skills they have learned. Thus, the Consortium’s system of assessment centers around tasks in various disciplines that are assessed using rubrics that focus on skills understood to be essential to the discipline. (An example of a task and rubric is here.)

In a Consortium school, students engage in extensive reading, writing, analysis, and discussion in all classrooms, which is work that builds toward the graduation or performance-based assessment tasks (PBATs) required of every Consortium student:

- An analytic essay on literature,

- A social studies research paper,

- An extended or original science experiment, and

- A higher-level mathematics problem.

Many schools add supplementary assessments in areas such as foreign language acquisition, creative arts, physical education, and community service.

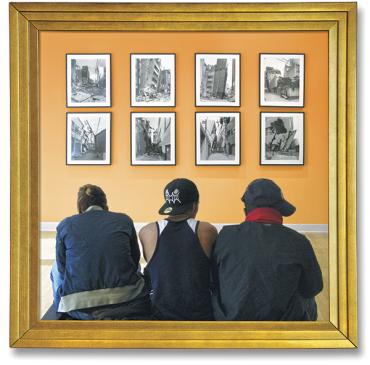

The rubrics are constructed working backward from an analysis of what knowledge and skills are required for college completion. Students demonstrate their learning through the PBATs, which are evaluated by external assessors. (For more on one external assessor’s experience, see "Learning on Display.") Such individuals have not taught the particular student whose work they are assessing, and they often come from local colleges or work in fields relevant to the subject discipline. Assessors respond to student work using the rubrics for both their written and their oral presentations.

In addition to providing guidelines for how the written work is to be assessed, the rubrics for each subject area also include an oral requirement: an unscripted conversation among external assessors who, through participation in students’ oral presentations, play an essential part of an authentic performance assessment.

To establish the reliability of these rubrics, Consortium teachers gather annually to participate in “moderation studies” where they regrade graduation-level PBAT papers using the subject area rubrics. They also examine the teacher assignments that helped generate the PBAT using a depth-of-knowledge assessment developed by educational research scientist Norman Webb.

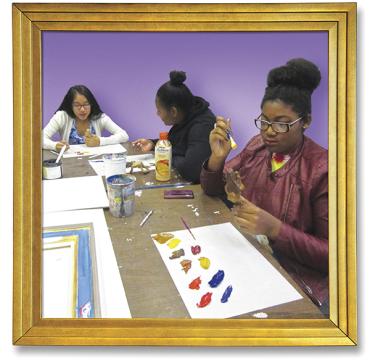

PBATs incorporate commonly accepted learning standards, enjoining students to write well, read analytically, punctuate properly, solve geometry problems, and be mathematically literate, but they also require students to do work that challenges and engages their thinking. For instance, such work includes researching and writing substantive essays that analyze different viewpoints; formulating, conducting, and analyzing the findings of their own science experiments; applying mathematical concepts to concrete problems; and interviewing adults who have subject-matter expertise. Consequently, the assignments, discussions, debates, experiments, and research projects that one sees in Consortium schools align with and often exceed college-level expectations and norms.

In Consortium schools, assessment tasks are based on curriculum and instruction; assessments are not imposed on them, which can lead to the teach-to-the-test syndrome that afflicts many public schools. With performance assessments, tasks become possibilities for further exploration only after students—with teacher input—have studied the material, discussed and debated it, and also carefully weighed what might make an interesting choice for a topic or a question. Such engagement strengthens the relationship between a teacher and a student, enabling both to invest in the task and take ownership of it.

Consortium schools also differ from traditional public schools in the diversity of course offerings, which also helps to keep students engaged. For example, in one Consortium school last year, social studies offerings included (but were not limited to) semester-long classes with titles such as Constitutional Law, the Civil War and Reconstruction, Popular Culture in the 1920s and the Present, Political Philosophy, Ethics, Biographies, the History of Black Cinema, Economic Policy and the American Dream, Modern Chinese History, India: Colonialism and Independence, the History and Politics of Disney Films, Puerto Rican History, Slave Revolutions, and Comparative Religion. In each of these courses, a wide variety of sources and teacher- and student-derived questions were explored. As is standard in Consortium schools, students are allowed to choose, with teacher input, which courses and performance assessments most interest them and suit them best.

Homework assignments complement course and assessment choices and build skills required to complete performance-based assessments. The homework requires students to support their opinions and interpretations with evidence and organize their thoughts coherently.

Teachers inform students when the work they have done on a particular assignment is strong enough to merit the research and revision process involved in producing a PBAT. To begin a PBAT, a student engages in a period of intensive work, which culminates in an oral presentation of a paper to a committee of outside examiners who discuss both the paper and related topics with the student.

The final paper is added to the collection of all the student’s performance-based assessments. At a minimum, the collection includes the literary essay, the social studies research paper, the original science experiment report, and the mathematics problem application. Additional PBATs as required by individual schools—such as artifacts from the student’s creative arts PBAT, evidence of second language learning, and internship reflections—are also included, as well as the rubrics used to assess the work.

The Impact on Students and Teachers

The results of the Consortium’s work have been well documented. Thousands of students’ lives have been positively affected, and hundreds of teachers have chosen to remain in the profession because of the responsibility and respect they have gained as Consortium teachers.

Consortium students include a larger percentage of minority and low-income students than the overall New York City public school population. Although they begin school with lower academic achievement, they graduate from Consortium schools and attend college at higher percentages. For example, the graduation rate of black students from Consortium schools is 74.7 percent, compared with 63.8 percent for all New York City public schools. For Latino students, the graduation rate from Consortium schools is also higher than the rate from all New York City public schools: 71.2 percent compared with 61.4 percent.11

Additionally, Consortium schools graduate twice as many special education students as New York City public schools and nearly double the number of English language learners. The four-year Consortium graduation rate for English language learners is 70.9 percent, compared with New York City’s rate of 37.3 percent.

And, compared with the larger public school system, Consortium schools boast higher college acceptance and persistence rates for all students and for students of color: 83.8 percent of the Consortium’s black graduating seniors and 88.3 percent of Latino graduating seniors are accepted into colleges, compared with national rates of 37 percent and 42 percent, respectively.12

Consortium teachers engage in a variety of tasks that are critical to a performance-based assessment system. They design challenging curricula and tasks, respond to student interests and needs, develop and revise rubrics, and participate in extensive Consortium- and school-based professional development. Collaboration is extensive, from observing each other’s classrooms to visiting each other’s schools and serving as external evaluators for performance-based assessments, sharing curricula, and evaluating each other’s work at the annual moderation studies.

The very nature of these schools enables Consortium teachers to teach differently; they strive to cultivate a learning environment in which student voices play a critical role. Instead of scripting predetermined questions and answers in the manner of some lesson plans, they learn to ask open-ended questions and respond to students’ answers, turning them into new questions, if necessary. They encourage students to explain their answers with support and to expand on them with evidence.

Moreover, in developing assignments and working with students to create performance assessments, Consortium teachers engage in intellectual work that parallels the work they demand of their students. Teachers routinely engage in the scholarly work of locating and presenting additional materials and sources for students’ consideration.

The PBATs complete this work. They give teachers a much more comprehensive picture of a student’s strengths and weaknesses and overall achievement. The teacher can then understand the student as a reader, a writer, and a thinker in ways that teaching focused on preparing students for high-stakes tests does not allow.

To support their growth as professionals, Consortium teachers spend considerable time collaborating with colleagues, observing each other’s teaching, discussing students, developing and critiquing an ever-expanding curriculum, and planning other joint work, such as team-taught courses and schoolwide projects.

The Consortium schools also participate in monthly workshops in which teachers from different schools exchange ideas about materials, methodology, student work, and challenges they face. These workshops currently include curriculum and teaching seminars in the four major disciplines (literature, social studies, science, and mathematics); a new school-mentoring project; a union representatives’ political education committee; a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer curriculum group; a special education group; and a college advisory counselors’ group. Through this work, the Consortium is creating a network where teachers can learn from each other to enhance their knowledge and skills.

Creating Equal Educational Opportunity

As the Consortium schools have shown, performance assessment is a clear and superior alternative to standardized testing because it enables teachers to make effective, productive judgments about what their students know and can do.

But performance assessment is not just a better method of assessing what students have learned; it also has a powerful impact on school culture, student engagement, and curriculum and instruction. What makes an authentic performance assessment system distinct from one that is commercially mass-produced is the professionalism of its teachers and the opportunity for student voices to be heard and respected.

Just as important, performance-based assessment exposes low-income students to challenging curricula. Although wealthier suburban districts may already provide their students with college-prep work, it is rare to see that level of intensity in urban schools located in high-poverty neighborhoods. The Consortium has changed that for our schools—including those in central Brooklyn and the South Bronx—and that achievement has been recognized by civil rights groups that have lauded the Consortium’s commitment to equality of educational opportunity.13

In addition to support from civil rights groups, the Consortium has also received recognition from the American Federation of Teachers. In 2013, the Consortium won the AFT’s Prize for Solution-Driven Unionism, a $25,000 award honoring local unions’ innovative approaches to complex problems.

Recognition of the Consortium’s work has also come from longtime Consortium supporter Pedro Noguera, a professor of education at the University of California, Los Angeles. In a talk given recently to a group of educators, Noguera explained the assumptions about students and learning that guide performance assessment:

If our aim was to prepare our young people to become responsible adults then we would actually approach the work very differently in many cases. First of all we would focus on helping young people to make good decisions. To think and reason, to problem solve, to think critically.

We have to recognize that as adults our students won’t just follow directions, they will have to make decisions on their own. It’s something that many parents have trouble with, because they often are afraid of what happens as their children get older, and they begin to lose the ability to control who their children’s friends are and how they spend their time. … And I would say that schools also play a major role in this.14

Noguera’s point is one that the emphasis on testing in the name of high standards tends to miss. Many highly publicized charter schools that tout their test scores are also places where student voice and self-expression are sacrificed in the name of restrictive rules and regulations. These schools’ guiding assumption seems to be that because their students come from lives of relative chaos (upon which order must be imposed), certain rights, responsibilities, and freedoms, as well as opportunities for intellectual inquiry and exposure to a challenging, nuanced curriculum, are inappropriate.

In the same talk, Noguera keenly observed that an overemphasis on testing dovetails with how students, especially low-income students, are expected to think and behave:

Unfortunately what is often driving these high-performing schools is the idea that the kids need to be broken. That the kids’ culture needs to be taken away from them and replaced with something else, because they come in with deficits. They come in as damaged goods. And these schools believe that their job is to mold the kids into something else.15

As one Consortium student put it, such an approach attempts to “take the community out of the kid.”

Consortium schools, of course, would agree.

The United States today faces growing inequality, which threatens our students’ futures and our own. The human rights challenge of our time must not involve preparing them to compete for diminishing shares of a fading American dream. Schools instead must help them reclaim it.

We should seek to enhance democracy by producing educated, thoughtful citizens ready and willing to tackle the daunting problems we face. We firmly believe the ability to analyze information and apply concepts to the real world is inextricably tied to the pursuit of equality and justice. Performance assessment engages this relationship in ways that a standardized test cannot. It directly connects the development of students’ academic, intellectual, and social skills while bringing students and teachers together in a joint process of learning—the very purpose of school.

Avram Barlowe has taught history and social studies in New York City public high schools for 35 years. A founding member of Urban Academy Laboratory High School, he is the school’s liaison to the New York Performance Standards Consortium. Ann Cook was the cofounder and codirector of Urban Academy Laboratory High School. She is the executive director of the Consortium.

*Vito Perrone, former vice president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, was a longtime opponent of standardized testing. Ted Sizer was dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the founder of the Coalition of Essential Schools. Deborah Meier, the first teacher to receive the MacArthur “genius” award, is a senior scholar at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development and is considered the founder of the small-schools movement. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. American Statistical Association, “ASA Statement on Using Value-Added Models for Educational Assessment,” April 8, 2014, www.amstat.org/policy/pdfs/ASA_VAM_Statement.pdf.

2. American Educational Research Association, “AERA Statement on Use of Value-Added Models (VAM) for the Evaluation of Educators and Educator Preparation Programs,” Educational Researcher 44, no. 8 (2015): 448–452.

3. Vicki Phillips, “The Common Core: Let’s Give Students & Teachers Time,” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, June 10, 2014, http://collegeready.gatesfoundation.org/2014/06/lets-give-time.

4. Sharon Noguchi, “California Exit Exam Abolished, Diplomas to Be Awarded,” San Jose Mercury News, October 8, 2015.

5. Valerie Strauss, “Common Core Takes a Hit: N.Y. Gov. Cuomo’s Task Force Recommends Overhaul,” Answer Sheet (blog), Washington Post, December 10, 2015, www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/12/10/common-core-take….

6. Lyndsey Layton, “At Least 500,000 Students in 7 States Sat Out Standardized Tests This Past Spring,” Washington Post, November 18, 2015.

7. Kate Zernike, “Obama Administration Calls for Limits on Testing in Schools,” New York Times, October 24, 2015.

8. Ann Cook and Phyllis Tashlik, “Making the Pendulum Swing: Challenging Bad Education Policy in New York State,” Horace 21, no. 4 (2005): 2–8.

9. Cook and Tashlik, “Making the Pendulum Swing.”

10. Lynette Holloway, “Parents and Educators Seek Regents Test Exemption,” New York Times, October 20, 1999.

11. Figures taken from analysis of New York City Department of Education graduation results data. See “Cohorts of 2001 through 2010 (Classes of 2005 through 2014) Graduation Outcomes,” New York City Department of Education, accessed December 30, 2015, http://schools.nyc.gov/Accountability/data/GraduationDropoutReports/def….

12. Educating for the 21st Century: Data Report on the New York Performance Standards Consortium (New York: Performance Standards Consortium, 2012), 5.

13. Marian Wright Edelman, James Forman Jr., Margaret Fung, et al. to Arne Duncan, letter, February 5, 2013.

14. Pedro Noguera, “Education Is about Preparing Young People to Make the World Better Than It Is” (speech, Morningside Center Courageous Schools Conference, New York, May 21, 2011).

15. Noguera, “Education Is about Preparing Young People.”

[illustrations by William Duke, photos by Roy Reid]