In the mid-20th century, democracies around the world were descending into authoritarianism—descents sparked by military coups. Today, military coups have become much less common, yet the threats to democracy have not abated. They now come in a different form: democratic erosion (also known as democratic backsliding).

Democratic erosion is a process by which elected leaders gradually dismantle democracy from the inside, aggrandizing executive powers and weakening institutions of accountability. Backsliding leaders harass the press, reduce the independence of the courts, defy legislative oversight, and undercut the public’s confidence in elections. In recent years, democracy has eroded in countries as varied as Brazil, Nicaragua, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Turkey, and the United States.1

Studies of democratic stability during the era of coups told us that wealthy and old democracies were the most resilient.2 And yet, the United States—the world’s oldest democracy, and one of its wealthiest—has shown new cracks in recent years. In 2016, the country elected a president who routinely attacked the free press, threatened to jail his political opponents, and expressed a consistent disdain for democratic norms in both his words and actions. He undermined confidence in elections by continually insisting that electoral fraud was widespread. When he lost the election in 2020, and even when he won the election but lost the popular vote in 2016, he maintained that the elections had been engineered through massive fraud.

During Donald Trump’s first term as president of the United States, many debated whether his election—and his subsequent eroding of democracy—was merely a fluke or something with more structural roots. Older models of democratic decay, which pinpointed low levels of economic development and a recent transition to democracy as risk factors, did not square with American democracy being in jeopardy. Indeed, some scholars argued that the threats to US democracy were overstated. Just two years ago, one model suggested that the “probability of democratic breakdown in the US is extremely low” and estimated that in 2015, US democracy faced less than a 1 in 3,000 chance of degrading to the level of Hungary.3 Viktor Orbán’s government in Hungary has eroded judicial independence, consolidated control of media outlets to promote propaganda and suppress dissenting voices, taken control of state universities, and changed electoral laws to favor his Fidesz party. At the same time, his government has targeted asylum seekers and LGBTQIA+ individuals, and corruption has skyrocketed.4

Our research shows that recent democratic decay in the United States is not a fluke—and the risk of further democratic decline is serious. Although the United States is often thought to be immune to democratic instability, it is not an outlier among countries experiencing democratic backsliding. In fact, it looks a lot like other eroding democracies in the 21st century. Today, the key structural factor that predicts democratic erosion is not wealth or economic growth or the age of the democracy: it is economic inequality. Highly unequal democracies are far more likely to erode than those in which income and wealth are distributed more equally.

Predicting Erosion

Where and when does democracy erode? The first step in answering this question is determining what features qualify a democracy as “eroding.” How do we distinguish between system-threatening executive aggrandizement (attempts to erode democracy) and more conventional executive overreach of the sort that could happen in any democracy? Recently, scholars have identified cases of erosion by tracking trends in horizontal and vertical accountability.5 A healthy democracy depends on heads of government—presidents and prime ministers—being constrained by voters (providing vertical accountability) and by the courts and the legislature, among others (providing horizontal accountability).

Expert surveys carried out by the Varieties of Democracy project allowed researchers to identify 23 distinct periods of erosion in 22 countries between 1995 and 2022. These countries are Benin, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Hungary, India, Mexico, Moldova, Nicaragua, North Macedonia, the Philippines (twice), Poland, Senegal, Serbia, South Africa, Turkey, Ukraine, the United States, Venezuela, and Zambia.6

What differentiates countries that have experienced erosion from those that have not (such as Canada, Finland, and Portugal7)? Are there factors that tell us that a democracy is more at risk of backsliding in one time period than in another? To answer these questions, we analyzed data from democracies around the world. We included information that generations of researchers have demonstrated help to predict military coups, including national wealth (gross domestic product per capita) and the age of the democracy (the number of years since a country became democratic and remained so, without interruption). We also included measures of economic inequality (including disparities in income and wealth). Inequality was not a highly reliable predictor of democratic vulnerability in the 20th century, when the threat was mostly military coups. But the connections (discussed below) between inequality and partisan polarization, and between inequality and public skepticism about institutions, made us suspect that democracies with especially big gaps between the rich and the poor might be prone to eroding.

We also suspected that backsliding by leaders is, in a sense, contagious. Backsliders often draw inspiration from other such leaders around the world. Hugo Chávez, for example, began his first term in 1999 by orchestrating a rewriting of the Venezuelan Constitution; his tactic was adopted by Latin American leaders who would erode their own democracies, such as Ecuador’s Rafael Correa in 2008 and Bolivia’s Evo Morales in 2009. Viktor Orbán began his drive to undermine Hungarian democracy in 2010. President Trump openly admired Orbán in 2019 when the two met; he claimed the Hungarian leader as his “twin.”8 On January 8, 2023, supporters of Brazil’s recently defeated president, Jair Bolsonaro, stormed the National Congress, Supreme Court, and presidential palace, convinced that the election had been “stolen” from Bolsonaro. The insurrection bore a striking resemblance to the January 6, 2021, riots by Trump supporters in the United States. The implication is that over time, erosion becomes increasingly likely: for each democracy that erodes, other aspiring autocrats around the world have more examples to draw from to undermine democracy.

Our analyses of these international data produced a consistent picture. In the 21st century, the key feature that distinguishes eroding democracies from those that hold strong is economic inequality. Income inequality is a highly robust predictor of where and when democratic erosion will take place. So is inequality in levels of wealth—that is, differences not just in income but in people’s overall economic assets. Either way, in more than 100 statistical models we ran, inequality was consistently related to the chances of erosion.

Some of the factors that had been shown in prior research to predict coups were less important in predicting democratic backsliding by way of power-aggrandizing elected leaders. National income per capita played a role but a smaller and less consistent one than inequality. And being an old, long-established democracy did little to protect democracies from the recent wave of erosion. By contrast, in the 20th century, older democracies were virtually immune to being toppled in military coups.

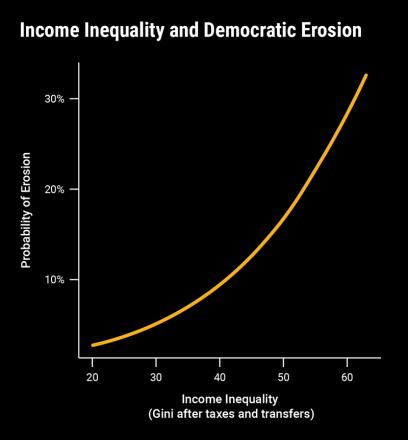

The figure below illustrates the relationship between income inequality and the risk of erosion. Where income inequality is low, the predicted probability of democratic erosion is near zero. But where inequality rises, the threat of erosion skyrockets—reaching a 30 percent chance in the most unequal democracies.

For the estimates presented in the figure, we measure inequality with the Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient takes a full distribution of incomes (or assets when examining wealth) in a given population and summarizes the level of inequality with a single number: higher values indicate greater inequality. In brief, we calculate it by ordering individuals in a population from lowest to highest income, then measuring the cumulative share of income earned by the bottom X percent of the population. In a situation of perfect equality, this cumulative share of income would be equivalent to the share of the population (50 percent of the population earns 50 percent of the total income, 95 percent of the population earns 95 percent of the total income, etc.). The Gini coefficient measures how much the actual income distribution deviates from this situation of perfect equality.*

This finding—that inequality robustly predicts democratic erosion—is not sensitive to the particular measure of inequality we use. In the figure, we looked at actual income after taxes and assistance from social safety net programs (like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), but the results were similar when we looked at wealth inequality and at the share of wealth or income concentrated among the top 1, 10, or 50 percent of the population. Across each of these metrics, higher inequality is associated with a higher risk of erosion. The greater the share of income going to—or wealth controlled by—the top 1 percent (or the top 10 or 50 percent), the greater the likelihood of backsliding.

Inequality and Polarization

Having observed that unequal countries are more prone to erosion, what are the mechanisms linking inequality to erosion? Why are unequal democracies more likely to erode? One of the key factors is polarization.

Specifically, there is great risk in affective polarization, a phenomenon in which individuals grow to detest members of opposing political parties.9 A central feature of affective polarization is that political identities become social identities. This is distinct from, say, ideological polarization—a measure of how far apart two parties are on policy positions. In an affectively polarized society, political affiliations take on a larger role in interpersonal relationships. People sort themselves into opposing camps and might be unwilling to engage with those who identify with a different party—or might engage with hostility. Politics becomes increasingly insular, and elections are often characterized by the fear of a despised opposing party coming to power.

Comparative research documents a robust relationship between inequality and polarization, both at the subnational level and in large cross-national studies.10 Countries with more unequal distributions of income have more polarized societies than those with more equal distributions of income; citizens living in US states with particularly high levels of inequality are more polarized than those living in states with less stark economic inequality.

In highly unequal settings, leaders can cultivate a sense of grievance among citizens who feel they have been left behind. Sometimes that grievance is aimed at economic and social elites; other times, at migrants and ethnic, racial, or religious minorities.11 Political leaders in countries like Turkey, Venezuela, and the United States have taken advantage of long-term inequality to exacerbate “pernicious polarization” among the “left-behinds.”12

Polarization, exacerbated by economic inequality, makes democracies more vulnerable to backsliding. Voters who live in highly polarized societies are often more tolerant of attacks on democratic institutions. When facing “acute society-wide political conflicts,” the stakes of elections grow.13 Aspiring autocrats leverage this situation to gain power: they present voters with a choice between safeguarding democracy or avoiding the presumably dire consequences that would follow a despised opposing party coming to power. Voters thus face a tradeoff between the cost of undesirable election outcomes and the value of democracy. As politics grows more polarized, the cost of undesirable outcomes rises and begins to outweigh the value of safeguarding democratic norms.

Tear It All Down

Polarization plays a central role in democratic backsliding, yet it’s not the only factor. In fact, democracy is on the defensive even in countries where parties are weak and few citizens identify with a political party. Even in the absence of partisan polarization, democracy is vulnerable to erosion if citizens place little value on protecting their current democratic institutions (or, in some cases, actively wish to see them dismantled).

When voters come to see, or can be led to see, their institutions as deeply flawed, a kind of cynicism can set in. Voters in effect ask themselves, “Why rally to the defense of institutions that are ineffective or corrupt?” When democracy fails to deliver positive outcomes for individuals, they grow more receptive to the appeals of aspiring autocrats who denigrate democracy. Put another way, when the game seems “rigged” in favor of the ultra-wealthy elite, why bother playing by the rules anymore? We call this public mood institutional nihilism, which we define as the belief that a democracy’s current institutions are incapable of solving critical problems. This is often expressed in a desire to “tear down” or “burn down” existing political institutions and start over with something else.14 In theory, this inclination could lead to a push for a more fair and democratic system—tearing down the institutions that foster systemic inequality and replacing them with new institutions that generate more equal opportunities for all citizens. But in practice, institutional nihilism is often wielded effectively by aspiring autocrats who promise to tear down the current system without presenting any clear plan for something better.

Why might people living in unequal societies be prone to institutional nihilism? Rampant inequality lends itself to a sense that the economic system is unfair. Those who are struggling see others thriving. The problem, then, is not that there isn’t enough to go around; it’s that the system is generating an unfair distribution of resources and opportunities. And if the rules are unfair (in the economic system), then why bother following them (in politics)?

Research shows that people who view inequality as the result of hard work or ability tend to view it as fair;15 however, when inequality is very high, people tend to see it as unfair, and it undermines people’s belief that they live in a meritocracy.16 High inequality also tends to reduce upward economic mobility.17 The scant prospects for upward mobility amid high inequality further contribute to a sense that the economic system is unfair and not meritocratic.18

The rhetoric of backsliding leaders leverages these feelings of unfairness and grievance. They frequently denigrate their countries’ institutions with interpersonal comparisons, noting that the rich and powerful take advantage of ordinary citizens, getting rich at their expense. In the 2016 US presidential race, Trump complained that “the people getting rich off the rigged system are the people throwing their money at Hillary Clinton.”19 In the context of a drive to undermine the credibility of Mexico’s electoral administration body, former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador accused it of enjoying “privileges” and “extremely high salaries.” In a similar drive against the courts, he complained of having “one of the world’s priciest judicial systems and one of the most inefficient. We’re wasting citizens’ taxes on a broken system.”20 According to backsliding leaders, institutions are failing because they are controlled by corrupt and nefarious actors who are indifferent or hostile to the interests of regular citizens.

Just as polarized constituents may reason that attacks on democracy are justified if they are necessary to keep the hated opposition out of power, nihilistic constituents may reason that attacks on democracy are justified given how flawed their democracy is in the first place. When backsliding leaders go after the courts, the press, the civil administration, or the electoral authorities, they can claim that they are not in fact harming a healthy democracy. Whereas autocratizing leaders’ polarizing rhetoric carries the implication that the capture of power by opposing political parties would be catastrophic, their democracy-denigrating rhetoric implies that the state is already corrupt and incompetent.

As a candidate for Brazil’s presidency in 2018, Jair Bolsonaro claimed that the Workers’ Party “has plunged Brazil into the most absolute corruption, something never seen anywhere [else] in the world.”21 Trump, similarly, drew a dire picture of the Democratic Party in 2018: “The Democrats have truly turned into an angry mob, bent on destroying anything or anyone in their path…. The radical Democrats, they want to raise your taxes, they want to impose socialism on our incredible nation, make it Venezuela…. They want to take away your health care…. Destroy your Second Amendment and throw open your borders to deadly and vicious gangs…. Democrats have become the party of crime.”22 And in 2023, Mexico’s then-President López Obrador regularly excoriated institutions, such as the federal courts, to convince the public that they were not worth saving. He asserted that Mexico’s courts were “riddled with inefficiency and corruption,” “taken over by white-collar crime and organized crime,” and “rotten.” He also attacked the people working in the judiciary, saying that they were “often influenced by money and grant protection to criminals” and were “not people characterized by honesty.”23

What’s Next? And What Can Be Done?

Do eroding democracies necessarily end up as dictatorships? That has not been the case thus far. Some countries have started out as democracies, undergone a process of erosion, and ended up as full autocracies. One sign of this decay is that they end up as countries in which heads of government are not chosen in free and fair elections. Such was the trajectory of Venezuela. In 1999, it was certainly a troubled democracy, but a democracy nonetheless. A quarter-century later, the president of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, lost the 2024 presidential elections, probably in a landslide.24 The regime claimed victory, Maduro remained in office, and his opponents are in prison and in exile.

Turkey is another country that at best teeters on the brink of full authoritarianism. Russia never became a full democracy but appeared headed in that direction, only to drift toward what is now a full dictatorship.

Yet this outcome is by no means inevitable. Backsliding leaders sometimes leave office, opening the way to a restoration of a better-functioning democracy. One route from power is by losing an election. In Poland, the conservative party (PiS) held control of the government beginning in 2015. Over the next eight years, PiS reduced the independence of the courts and the press and followed a series of strategies in the would-be autocrats playbook—but in 2023, PiS lost its parliamentary majority and hence its hold on power.25 Depending on how far backsliding has gone, and on leaders’ determination to cling to power even when they lose, backsliding leaders do not always respect the outcomes of elections. Trump tried to flout the outcome of the 2020 presidential election in the United States, and Bolsonaro did the same in the 2022 election in Brazil. In both cases, the courts remained sufficiently independent and respectful of the rule of law to stand up against these attempts.

Other backsliders have been forced out by their own political parties. This is what happened to the South African leader Jacob Zuma in 2018. His political party, the African National Council, forced him to resign.26 Something similar happened in the United Kingdom in 2022. Prime Minister Boris Johnson had not taken his country fully down the path toward erosion. But he had sidelined the Parliament, reduced the right to protest, threatened unfriendly news outlets, and undermined the integrity of elections in the public’s eye. His Conservative Party forced him to resign.27

Though these paths to ousting backsliding leaders appear distinct, they both boil down to these leaders losing popular support. Trump in 2020, Bolsonaro in 2022, and PiS in 2023 all commanded insufficient electoral support to stay in office. Zuma in 2018 and Johnson in 2022 were forced out by their parties because they were viewed as likely to lead their parties to defeat should they stay in office.

A critical question, then, is what leads the public to withdraw support from backsliding leaders? We saw that institutional nihilism and polarization—and behind these two factors, income inequality—shore up backsliders’ public support. Do they leave power only when confidence in institutions increases, partisan polarization ebbs, and wealth becomes more equal?

Since such progress would presumably take hold only over long periods of time, it is fortunate that the answer to the question is no. Sometimes the public turns against presidents, prime ministers, and their governments in reaction to their attacks on democracy. The arbitrary exercise of power can put voters off, especially when times are hard. In the United Kingdom, voters, including Conservative Party voters, suffered greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic. When they became aware that their prime minister and people around him flouted the restrictions that they imposed on their constituents, the hypocrisy combined with the hard times led to a caving of support for the government.

Indeed, though studies of backsliding governments have emphasized polarization and loss of confidence in institutions, backsliding leaders are often evaluated on the standard metrics of performance, especially economic performance. Trump was hurt in his 2020 reelection bid by the pandemic and the economic travails that it brought in its wake. In turn, he was aided in his 2024 reelection by voter frustration with inflation and the high cost of living.

Still, social scientists have learned a great deal about how to de-polarize people and increase their confidence in democratic institutions. On the former, a polarized public views political identities as correlated with most other aspects of their lives. The hated “other side” likes different food, wears different clothing, has a different sense of humor, etc. In fact, research shows that polarized individuals have exaggerated views of how far apart they are from opposing partisans even on matters of public policy. Exposing people to those with opposing party identities has been shown to reduce their levels of mutual animosity.28

Exposure to accurate information can also boost people’s confidence in democracy and its institutions. An experiment that showed people videos of protesters suffering postelection repression in authoritarian or backsliding countries made them more favorable toward measures that would strengthen democracy, even measures that were not closely related to freedoms of speech, assembly, or protest.29

We have also learned that backsliding leaders’ disparaging statements about institutions can be neutralized by more accurate, positive statements. For instance, in one study, the researchers first exposed Mexican respondents to their president’s caricatured account of the country’s national election administration body, in which he claimed that it was utterly corrupt and sponsored mass voter fraud. They then exposed some respondents to a corrective statement that rightly noted the high international reputation of that body and its role in helping Mexico transition into democratic governance at the beginning of the 21st century. The rebuttal improved people’s views of the election body, even those who were supporters of the backsliding leader’s political party.30

Of course, in addition to positive messages and the correction of misinformation, there is a longer-term need for structural reforms. When institutions work badly, it is easier for leaders to claim that not much is lost when they tear them apart. And our research shows that, whatever the moral and economic arguments for more equal distributions of income and wealth, there is a powerful political argument. Improving income and wealth distribution turns out to be an investment in a resilient democracy.

Eli G. Rau is an assistant professor of political science at Tecnológico de Monterrey. He researches democratic erosion, political participation, and electoral institutions. Susan Stokes is the Tiffany and Margaret Blake Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago and president-elect of the American Political Science Association. Her latest book, The Backsliders: Why Leaders Undermine Their Own Democracies, was published by Princeton University Press in September 2025. For a more detailed look at the research Rau and Stokes share here, see “Income Inequality and the Erosion of Democracy in the Twenty-First Century,” which they coauthored for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2025.

*Here are additional details to visualize what the Gini coefficient means. We first order individuals in a population from lowest to highest income. We then create a graph, marking on the x-axis the cumulative share of the population (following this lowest-to-highest-income ordering) and on the y-axis the cumulative share of income earned by the bottom X percent of the population. If there were perfect equality, the graph would show a 45-degree line (x = y): for any value X, the “bottom” X percent of income-earners receive X percent of the total income. Next, we draw the line of perfect equality and the curve representing the actual income distribution (where the bottom 95 percent of the population might only be earning, say, 60 percent of the total income)—this is called the Lorenz curve. The Gini coefficient is a measure of how far the Lorenz curve falls below the line of equality (we calculate the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of equality as a proportion of the entire area below the line of equality). (return to article)

Endnotes

1. M. Laebens, “Beyond Democratic Backsliding: Executive Aggrandizement and Its Outcomes,” Working Paper Series 2023:54, Varieties of Democracy Institute, v-dem.net/media/publications/UWP_54.pdf.

2. J. Londregan and K. Poole, “Poverty, the Coup Trap, and the Seizure of Executive Power,” World Politics 42, no. 2 (January 1990): 151–83; and A. Przeworski and F. Limongi, “Modernization: Theories and Facts,” World Politics 49, no. 2 (1997): 155–83.

3. D. Treisman, “How Great Is the Current Danger to Democracy? Assessing the Risk with Historical Data,” Comparative Political Studies 56, no. 12 (2023): 1924–52.

4. F. Garamvolgyi and M. May, “Inside Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Not-So-Secret Mission to Elect Trump,” CBS News, November 2, 2024, cbsnews.com/news/viktor-orban-mission-to-elect-trump.

5. Laebens, “Beyond Democratic Backsliding.”

6. Laebens, “Beyond Democratic Backsliding”; and E. Rau and S. Stokes, “Income Inequality and the Erosion of Democracy in the Twenty-First Century,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no. 1 (2025). Some scholars have critiqued the use of expert surveys to measure democratic erosion, but others have noted that the Varieties of Democracy is among the highest-quality sources of comparative data on quality of democracy. See “Comment and Controversy: Special Issue on Democratic Backsliding,” PS: Political Science & Politics 57, no. 2 (April 2024) for a debate over the role of expert surveys in democracy research. We note that the set of countries identified through Laebens’s erosion method is very similar to those identified by other scholars using alternative methods (see, for example, S. Haggard and R. Kaufman, Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021). And by assessing specific metrics of horizontal and vertical accountability (Does the executive comply with court rulings? Do election management bodies have autonomy to apply election laws impartially?) as opposed to broad assessments of whether democracy works well in a given country, this method further reduces the scope for bias and subjectivity in measurement.

7. Laebens, “Beyond Democratic Backsliding”; and Rau and Stokes, “Income Inequality.”

8. Z. Simon, “Trump Compared Orban to a Twin Brother, Ambassador Says,” Bloomberg, May 15, 2019, bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-15/trump-compared-orban-to-a-twin-brother-envoy-tells-444-hu.

9. N. Gidron, J. Adams, and W. Horne, American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, November 2020).

10. Gidron, Adams, and Horne, American Affective Polarization; Y. Gu and Z. Wang, “Income Inequality and Global Political Polarization: The Economic Origin of Political Polarization in the World,” Journal of Chinese Political Science 27, no. 2 (June 2022): 375–98; J. Voorheis, N. McCarty, and B. Shor, “Unequal Incomes, Ideology and Gridlock: How Rising Inequality Increases Political Polarization,” SSRN, August 23, 2015, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2649215; and J. Garand, “Income Inequality, Party Polarization, and Roll-Call Voting in the U.S. Senate,” Journal of Politics 72, no. 4 (October 2010): 1109–28.

11. A. Alesina and E. La Ferrara, “Ethnic Diversity and Economic Performance,” Journal of Economic Literature 43, no. 3 (September 2005): 762–800; A. Alesina and E. Glaeser, Fighting Poverty in the US and Europe: A World of Difference (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004); and J. Roemer, “Why the Poor Do Not Expropriate the Rich: An Old Argument in New Garb,” Journal of Public Economics 70, no. 3 (December 1998): 399–424.

12. J. McCoy, T. Rahman, and M. Somer, “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities,” American Behavioral Scientist 62, no. 1 (January 2018): 16–42.

13. M. Svolik, “Polarization Versus Democracy,” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 3 (July 2019): 20–32.

14. For discussion of a related concept of “Need for Chaos,” see K. Arceneaux et al., “Some People Just Want to Watch the World Burn: The Prevalence, Psychology and Politics of the ‘Need for Chaos,’” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 376, no. 1822 (April 2021): 20200147.

15. K.-S. Trump, “When and Why Is Economic Inequality Seen as Fair,” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34 (August 2020): 46–51.

16. L. McCall et al., “Exposure to Rising Inequality Shapes Americans’ Opportunity Beliefs and Policy Support,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 36 (September 2017): 9593–98; and N. Heiserman, B. Simpson, and R. Willer, “Judgments of Economic Fairness Are Based More on Perceived Economic Mobility Than Perceived Inequality,” Socius 6 (2020): 2378023120959547.

17. M. Corak, “Do Poor Children Become Poor Adults? Lessons from a Cross-Country Comparison of Generational Earnings Mobility,” in Dynamics of Inequality and Poverty, ed. J. Creedy and G. Kalb (Leeds, UK: Emerald Publishing, 2006); D. Andrews and A. Leigh, “More Inequality, Less Social Mobility,” Applied Economics Letters 16, no. 15 (2009): 1489–92; A. Krueger, “The Rise and Consequences of Inequality,” speech, Center for American Progress, Washington, DC, January 12, 2012; and M. Kearney and P. Levine, “Income Inequality, Social Mobility, and the Decision to Drop Out of High School,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Brookings, 333–80, brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/kearneytextspring16bpea.pdf.

18. Heiserman, Simpson, and Willer, “Judgments of Economic Fairness.”

19. D. Trump, “Remarks at a Rally at the New Hampshire Sportsplex in Bedford, New Hampshire,” speech, New Hampshire Sportsplex, Bedford, NH, September 29, 2016, presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-rally-the-new-hampshire-sportsplex-bedford-new-hampshire.

20. L. Cella et al., “Building Tolerance for Backsliding by Trash-Talking Democracy: Theory and Evidence from Mexico,” Comparative Political Studies (March 20, 2025), journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00104140251328024.

21. J. Bolsonaro, “01/10/2018: Bolsonaro, Política e Questões Nacionais,” Jair Bolsonaro, YouTube, January 10, 2018, youtube.com/watch?v=6117jbeHBD0.

22. D. Trump, “Remarks at a ‘Make America Great Again’ Rally in Missoula, Montana,” speech, Missoula, MT, October 18, 2018, presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-make-america-great-again-rally-missoula-montana.

23. Cella et al., “Building Tolerance.”

24. A. Herrero and S. Schmidt, “Maduro Likely Lost Venezuela’s Election but Refuses to Leave. What Now?,” Washington Post, September 6, 2024, washingtonpost.com/world/2024/09/06/maduro-survives-election-opposition-options.

25. R. Picheta, “Poland’s Law and Justice Party Loses Power After Eight Years of Authoritarian Rule,” CNN, December 12, 2023, cnn.com/2023/12/11/europe/poland-pis-confidence-vote-tusk-intl/index.html.

26. J. Campbell, “Finally, Jacob Zuma Resigns as President of South Africa,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 15, 2018, cfr.org/blog/finally-jacob-zuma-resigns-president-south-africa.

27. L. Nathoo and S. Francis, “Why Did Boris Johnson Resign?,” BBC, June 9, 2023, bbc.com/news/uk-politics-65863730.

28. Bright Line Watch, “Tempered Expectations and Hardened Divisions a Year into the Biden Presidency,” November 2021, brightlinewatch.org/tempered-expectations-and-hardened-divisions-a-year-into-the-biden-presidency.

29. J. Voelkel et al., “Megastudy Testing 25 Treatments to Reduce Antidemocratic Attitudes and Partisan Animosity,” Science 386, no. 6719 (October 18, 2024): eadh4764.

30. B. Bessen, S. Stokes, and A. Uribe, “Can Rebuttals Restore Confidence in Eroding Democracies?,” working paper under review, Chicago Center on Democracy, 2025.

[Illustrations by Adrià Fruitós]