The student loan crisis is hardly new, but a recent report shows that in addition to its debilitating effect on students at large, it hobbles particular groups of students far more than others. Not only are default rates soaring, they are significantly worse for students at for-profit colleges, and they are at "crisis levels" for students of color. The report, released by the Brookings Institution this month, calls for "robust efforts" to regulate for-profits, improve degree attainment for all students and particularly address challenges faced by students of color.

Currently, student debt stands at a staggering $1.4 trillion and is second only to housing as the largest source of household debt. This study shows the various ways this affects different people, examining subgroups of borrowers. The study also spans a longer period of time than previously considered—as much as 20 years; it looks at two cohorts of borrowers, one that first entered college in 1995-96 and the other that entered in 2003-04.

Here are the top findings:

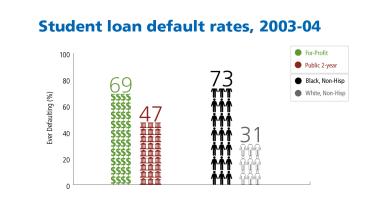

- Borrowers who attend for-profits default at twice the rate of borrowers who attend public two-year institutions (52 percent of for-profit borrowers default after 12 years versus 26 percent of public two-year borrowers).

- Because for-profit students are more likely to borrow, the default rate among all for-profit students is nearly four times what it is among all students at public two-year institutions.

- Black BA graduates default at five times the rate of white BA graduates (21 percent, compared with 4 percent).

- Based on trends among the 1995-96 cohort, nearly 40 percent of the 2004-05 cohort may default on their students loans by 2023.

For-profit colleges have long been criticized for luring students with the promise of an excellent education that will guarantee a well-paying job, only to provide mediocre classes that do not equip students for the job market. Some students, ill-prepared for their programs, drop out still owing thousands in student loan debt; those who graduate often lack real credentials and cannot find work that will help them pay off their debt.

Targeting vulnerable people

These colleges target vulnerable populations for enrollment, including low-income students, single mothers, veterans and first-generation students who are unfamiliar with college requirements and culture.

Regarding the higher default rate among people of color, experts point to several factors. A lack of generational wealth is one—with a legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, many black families have simply not had the time to accumulate any reserves. Often black students are first in their families to attend college, which adds another layer of challenge to navigating the student loan process and makes them vulnerable to the high-pressure marketing tactics typical of for-profit colleges. For-profits also work at making enrollment easy, and for students from neighborhoods where under-resourced public schools may not have prepared them well for college, the open enrollment is attractive.

But enrollment can be disastrous. "For-profit institutions are not just expensive. They are risky," says Tressie McMillan Cottom, whose book Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy provides a deep study of for-profit operations and the social and economic dynamics that drive them. "These data highlight that the risk of borrowing and the risk of defaulting in pursuit of the American dream is disproportionately shouldered by women, low-income people, African-Americans and especially African-American women.

"At the individual, group and societal levels, this kind of predatory inclusion of the most vulnerable students is intolerable," she says. "It is also unsustainable. We can and must do better if our true goal is alleviating poverty and facilitating educational justice."

Personal impact

It's not hard to find examples of this struggle. Saundra Mobley, a paraprofessional and AFT member in Florida, is still trying to repay the student loans that put her through Corinthian College, an institution that closed in 2015. The "education" she got there left her barely able to pay her bills, much less her student loans, and she still lacks the credentials she needs for a job in her field. "I know education is the key to advancing my career, but it's been a rough road getting there," she says.

Another student, who attended a dental technician program at the now-defunct Everest, a Corinthian College in Milwaukee, described the inadequate education this way: "Everything they promised was a lie. I could talk all day about how my decision to go to this career college ruined my life. But unfortunately I don't have enough time in my day because I am working two jobs as a housekeeper and personal aide and have two children to take care of."

The AFT has championed debt forgiveness for students whose for-profit colleges have cheated them of a good education, but under U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, rules around debt forgiveness are making relief more elusive. Similarly, the DeVos Education Department wants to loosen regulations that require for-profits to show their programs lead to gainful employment. Hearings about proposed regulations changes are ongoing, and the AFT continues to advocate for relief from student debt.

[Virginia Myers]