Amid paralyzing budget cuts, massive midyear educator layoffs and, suddenly, a pandemic and shutdown, public school students in Rochester, N.Y., have delivered one clear message: If our schools are under attack, we will fight back.

That fight became all the more urgent in mid-April as education budgets in New York school districts from Rochester to Albany began to take huge additional hits from unexpected COVID-19 expenditures.

Students have jumped in. From late-night speechifying at local school board meetings to direct action at the governor’s door in Albany, from sitting down with a 400-page school budget to participating in a car caravan through city streets, from virtual town halls to Zoom meetings, the students of Rochester have found extraordinary ways to be heard in a battle to keep their schools staffed and funded.

And, no, the pandemic is not obstructing these newly skilled activists. In fact, the locked and chained school doors may be teaching this community how important its public schools really are.

The Rochester funding debacle started last December with a sudden and devastating delivery of layoff notices to nearly 200 educators in city schools. At the time, a small group of Rochester public school students was just one month into the Teen Activist Project run by the New York Civil Liberties Union. They were new to activism but poised to pounce. To protest the educator cuts, Simone Hardaway, a senior at School of the Arts, attended her first school board meeting just before Christmas. “It was packed,” she says. “People were very angry. Little kids—just 8 years old—were giving speeches they’d written themselves, and crying.”

TAP activists found that everyone—parents, school employees and their own student cohort—was shocked by the sudden news of a budget shortfall and then massive cuts. They quickly set their goals: In Rochester, save the teachers. And in Albany, fight for Rochester schools’ share of the state’s Foundation Aid—funding for public schools, long denied, that would help to close the budget gap. “Legislation moves fast,” Simone learned quickly, “so we have to move faster.” The target was an April 1 budget vote in the state Assembly.

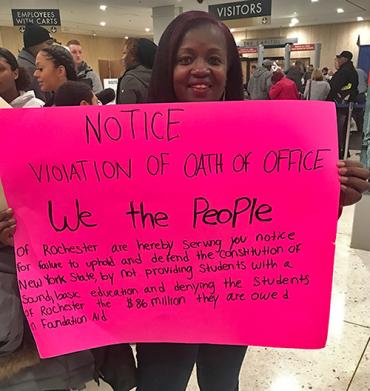

In February, the TAP activists joined two busloads of students who rode to Albany to lobby the governor. They argued that the state owes Rochester $86 million in Foundation Aid. Its failure to deliver those funds, they asserted, is a violation of students’ constitutional right to a basic education. To honor their laid-off teachers, the students prepared “pink slips” for Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Each slip described the damaging personal effects of education cuts. But when the buses arrived at the state Capitol, they found that the governor was out of state and his entryway had been hastily locked by security guards. So, jammed into the hallway, the crowd of students slid each pink slip through a crack in the door.

Tali Beckwith-Cohen, a TAP member from School of the Arts, was in the crowd outside the governor’s door. “I am angry about gross inequity and discrimination in the funding of our schools,” she says. “It’s a clear injustice when districts like mine, districts with some of the highest rates of childhood poverty, are not given the resources necessary to meet the needs of the students who rely on them. We deserve better.” She adds, “In a state that has so much wealth and so many millionaires, it makes me furious.”

Tali wasn’t alone in her focus on funding. A coalition of community, education, labor and faith-based organizations was quickly forming around a revenue campaign. Included in the new Rochester Community Coalition to Save Our Schools—ROC-SOS—were the Rochester Teachers Association and the Rochester Association of Paraprofessionals. By mid-April, 100 other groups and individuals had signed on.

Diversity is a hallmark of the student activists. The Monroe County delegation of the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Youth Leadership Institute includes city and suburban students who all jumped in. “We’ve been trained to do research and speak out,” says Yaide Valdez, a student at Young Women’s College Prep Charter School. “We know, eventually, these cuts will affect the budget for every school in Monroe County. If students in the city are protesting in the middle of the school day,” she says, “we should step up, too!”

Another PRHYLI member, Lluvia Ayele-Pound, scripted and produced a video of a cross section of students commenting on the budget disaster. Of the teacher cuts, she says, “Whoa! We already have a teacher shortage. How can they lay off more?” Lluvia’s own beloved elementary school is now slated for closure. “We know that teachers, coaches, even principals can be fired for speaking out, so we have to speak up for them.” The 2½-minute video calls on the larger Monroe County community to, quite simply, show up and care.

It worked. A band of suburban students reached out; they call themselves “the secret weapon.” They don’t attend Rochester city schools, but they worry about friends and relatives who do. Grace Pazmiño, a junior at suburban Fairport High School, is outraged by inequities in education. “We go to well-funded schools,” she says. “It’s too easy for people like us to just ignore what’s happening a couple miles away. We have to stick up for people who should get the same education we are given.” Her schoolmate, Ivan Widlund, adds, “You haven’t see a lot of this in the history books, but today, students really care about equality.”

Alumni, too, are joining. “I graduated before the budget cuts,” says Christian Ramos, a student at Rochester Institute of Technology. “Now when I look at our high schools, I think of what’s stripped away. Kids are losing teachers who acted as mentors and mothers, and someone to talk to when no one’s at home. It’s got to hurt.”

In March, as momentum grew toward the budget vote in Albany, other events sprung up, including a mid-March town hall meeting called “Fund Our Schools, Tax the Rich.” With hashtags like #MakeBillionairesPay, it called for a hard look at local and state budgets. TAP activists began to circulate a funding petition. “About the billionaires, people say, ‘Well, it’s their money,’” says Simone Hardaway. “But, really, no. At what point do you realize there are people starving in your community, or not getting an education, while your family just gets richer?”

That divide between rich and poor is painfully visible to Angie Rivera, president of the Rochester Association of Paraprofessionals. “We see hunger every day in the children we work with. Some of my own members are on public assistance, too. But let’s be clear: It’s not the rich people who are failing our students; it’s our elected leaders. They have the power to make change, but they do not act. We need to elect more leaders like Assemblyman Harry Bronson and state Sen. Robert Jackson, who are creative and uncompromised in their support for public education in our state.”

On April 1, Rochester’s students celebrated a significant victory in Albany when the state Assembly allocated $35 million to help the Rochester City School District finish the year.

But their elation didn’t last. Soon after, the RCSD school board laid out another, more severe, round of budget cuts for the 2020-21 school year. New targets for cuts include:

- English as a second language programs;

- The Rochester International Academy for refugees;

- The Bilingual Academy;

- The Young Mothers Program;

- Social workers, counselors, and more teachers and paraprofessionals; and

- Additional school closures.

Adam Urbanski, president of the Rochester Teachers Association, observed, “It’s like the district got together and asked, ‘How can we hurt our most vulnerable—the bilingual students, the refugees, the immigrant children from Puerto Rico, the teen mothers.’ In short, it’s the least enfranchised and the least empowered among us.”

Yet TAP responses continue to be creative and undiminished. On just one day, April 23, students cheerfully overcame the challenge of social distancing by:

- Joining an 80-car caravan that honked as it passed the Rochester school district building, with posters taped to car windows that read, “What about the kids?” and

- Appearing later in an online Zoom session to offer a passionate new bill of rights—and demands—in a “State of the Students” report, Tali Beckwith-Cohen did not hold back.

But both events collided that day with a bleak announcement from the school district’s newly minted superintendent that he plans to abandon the district, less than a year into his three-year contract. He said that negotiations with the school board over next year’s budget are fatally stalled; he wants out.

The students were stunned, and their response was immediate. In their “State of the Students” address, they said: “We have a right to state and city leaders who will stick their necks out for us.” The teen activists also returned to the theme of Foundation Aid, which was now attached to actual legislation in the state Senate, writing, “State Sen. Robert Jackson has created a bill – S.7378 – to tax the ultra-wealthy (with incomes over $30 million annually). In four years, this bill will completely fund New York state’s Foundation Aid.”

The students’ message is clear: Even now, as the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the punitive inequalities in Rochester’s public school system, they will stay in the battle.

“I thought my fight would be over when we got our Foundation Aid,” says TAP activist Simone Hardaway. While that help has not arrived, her activism has opened her eyes. “I’ve seen that other schools have bathroom doors and books. Other schools have teachers—while we got midyear cuts. Our students still have needs. We still have a high poverty rate.”

“In the past,” Simone continues, “when I didn’t know the words ‘systemic racism,’ I would have said, ‘Oh, it’s just not fair.’ Now I can see that black and brown students are targeted, and it’s growing more severe. We didn’t have many resources in the first place, and now those resources are getting cut off.”

“This is a fight,” she says, “that’s never done.”

[Connie Mckenna]