The AFT has long championed community schools as one of the most promising ways to knit together students, families and educators so everyone benefits. These centers of community life look different in different places—some might feature English language classes and immigration workshops for families; others offer robust after-school programming, social services, shared gardens and food pantries. All of them strive to connect families with the services they need, utilizing partnerships and district resources to provide counseling, enrichment programs and so much more.

“From services for immigrant and refugee families in Kansas City, Mo., to financial literacy classes and adult education in Cincinnati, to clothes closets with everything from winter coats to prom dresses in Boston, community schools are one of the most effective strategies we have to help students and their families thrive,” says AFT President Randi Weingarten, who toured a succession of community schools this spring.

There are close to 900 community schools in the AFT family; we are aiming to reach 2,500 in the next three years, and we support our national partners such as the Coalition for Community Schools in their push for 25,000 community schools by 2025. Our intensive workshops have already helped build community school networks like the one in Rome, N.Y., and we work hard to steer members toward federal grants made available by the Biden administration, which increased community school grants by $125 million between 2020 and 2023.

Weingarten calls community schools “a powerful antipoverty strategy” where school staff “lessen life’s hardships” with connections to physical and mental health care, legal services, English classes and housing.

Here are snapshots of five community schools Weingarten visited recently, highlighting what makes each special. To learn more about community schools, listen to her conversation with two community school advocates and union leaders on our “Union Talk” podcast.

Valuing community culture in Boston

Community schools in Boston exist in part because of the Boston Teachers Union’s yearslong campaign for wraparound services in schools. But it’s not just counseling and social services that makes these places tick; it’s how they empower students and families in shared decision-making.

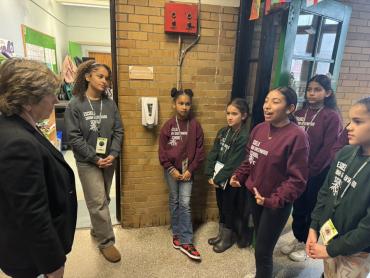

It was students who took Weingarten on a tour of the Sarah Greenwood School, a K-8 school where student/family surveys help inform decisions about what programming is adopted. Currently the school hosts on-site counseling and student and family support services; there are also literacy support coaches and a reading recovery specialist.

At Mario Umana Academy, another K-8 school in Boston, staff follow community needs and schedule after-school programs around parents’ work schedules so every family can participate in swimming lessons, culturally relevant dance classes, soccer and more. The school is a dual-language academy. It is developing a library where half the books will be in English and the other half in Spanish, and it’s always working to weave familiar language and culture into the students’ experiences.

See a video of the Boston school visits here.

A home for everyone in San Francisco

San Francisco has 50 community schools in various stages of implementation, and educators—who are members of the United Educators of San Francisco—can feel confident that they will always have a voice in how community schools are run, thanks to union contract language that codifies union, student, family and community member participation in decision-making.

That voice at the table, and the trust educators have built with students and families, makes it easier to respond to community needs. So when school staff at Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School learned that housing was one of the biggest problems in their community, and that many students did not know where they would sleep at night, they worked with families and community leaders to establish a shelter right on campus. Since 2017, the school’s Stay Over program has provided a safe space for hundreds of unhoused students and families. As Weingarten said in her April column, “Rather than arriving at school exhausted, hungry and stressed—or not getting to school at all—unhoused students in the Stay Over program at least are rested and nourished. And the families feel supported, not judged.”

The union also helped win $60 million annually to support community schools; the funds were secured after 76 percent of voters approved a ballot measure championed by a coalition of young people, parents, community members and the union. “When we come together to unite for our young people, really amazing things can happen,” says Leslie Hu, community schools coordinator for the district.

Teamwork and training in Washington, DC

Washington Teachers’ Union President Jacqueline Pogue Lyons was determined to get community schools off the ground in Washington, D.C., so she convinced administrators to learn more, inviting them to attend AFT-sponsored workshops in Philadelphia and New York City. The effort paid off: Community schools like Kimball Elementary School are growing. At Kimball, a Title I school that has been nationally recognized for its STEM program, kids get hands-on science, nutrition and even history in the school garden; parents can access on-site laundry facilities; and a food pantry and clothing closet support families who need them. “The community schools initiative brings to the forefront how the schoolhouse is really the nexus of the community,” says Kimball math coach Nadia Torney.

Check out our video of Weingarten’s visit to Kimball.

Echoing the past to build the future in Chicago

Community schools don’t just happen on their own. They take months, sometimes years, of organizing, connecting with families and community members and building up trust and relationships. They also require funding. The Chicago Teachers Union has partnered with Chicago Public Schools to administer a $500,000 grant fund for wraparound services at community schools, and it is currently working to grow its roster of community schools from 20 to 200.

Collins Academy High School could be one of those new community schools. Set in North Lawndale, a majority Black neighborhood that has been neglected by the city for years, the school has nevertheless excelled: Attendance and enrollment are rising, and 100 percent of graduating seniors were accepted to college in 2023. Mayor Brandon Johnson toured the school with Weingarten and CTU President Stacy Davis Gates in April, expressing his support for more community schools in the city. “This is about making sure that every single child has a library or librarian, wraparound services, class sizes that are manageable,” Johnson said. “There’s a lot of work to be done, but unfortunately, because of a long history of systemic racism, disinvestment has left our communities in despair.”

Equity is at the heart of the community schools movement in Chicago, where change is often driven by the community. In 2001, as CTU describes it, “parents, grandparents and community activists” engaged in a hunger strike to protest denial of a new high school for the children of their working-class, Latinx community, and eventually won the new Little Village Social Justice High School. In 2015, another hunger strike influenced the reopening of Dyett High School, which became one of the first sustainable community schools established through CTU’s collective bargaining agreement with the school district.

[Virginia Myers]