While OSHA’s lack of progress in the healthcare sector is frustrating, it’s important to remember that the existing standards written into the Occupational Safety and Health Act provide important protections for healthcare workers and worker rights. The better you understand OSHA, the more effective you can be in using OSHA to protect yourself, your colleagues, and your patients.

Federal OSHA enforces the law for all federal employees and for private sector employees in 29 states, the District of Columbia, and the US Virgin Islands, as well as for private sector employees working for federal agencies in American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The other 21 states and Puerto Rico run their own OSHA programs. Federal OSHA funds up to 50 percent of these OSHA state plan budgets, but the law dictates that the state plan programs must be “at least as effective” as the federal program. States also have the option to issue standards that are more effective than federal OSHA’s.1 For example, California’s OSHA program has exceeded federal OSHA by issuing an ergonomics standard, a healthcare workplace violence standard, a COVID-19 emergency temporary standard, and a standard covering all aerosol transmissible diseases. Minnesota’s hazard communication standard includes infectious diseases as well as chemicals.

Public Employees: Second-Class Citizens

One glaring problem is that federal OSHA does not actually cover all workers. Public employees are not covered by federal OSHA, although the law requires the 21 states with their own OSHA plans to cover state, county, and municipal employees. Six additional states take advantage of a provision in the law that allows states to choose to cover only their public sector employees, while federal OSHA continues to cover the private sector. OSHA also funds 50 percent of these public sector programs.* At this time, public employees in 23 states and the District of Columbia—including those who work in public healthcare facilities—have no legal right to a safe workplace.†

Healthcare workers in the public sector pay a high price for lack of OSHA coverage. In 2017, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that state government healthcare and social service workers were nearly nine times more likely to be injured by an assault than healthcare workers in the private sector. Those working in mental health facilities suffer the most. In 2019, the rate of assault-related injuries for state psychiatric aides was an astronomical 1,460.1 per 10,000 workers.2 OSHA can’t even use the weak General Duty Clause to protect public healthcare workers in 23 states and the District of Columbia, and even if OSHA eventually issues a workplace violence standard, public employees in those states will not be covered.

OSHA Standards

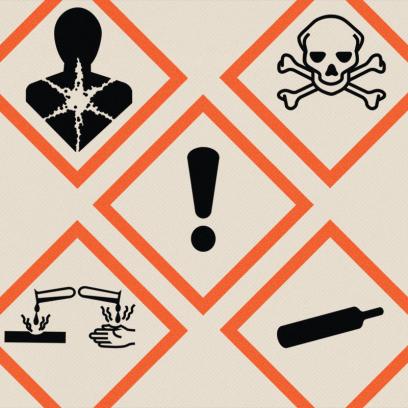

OSHA protects workers mainly through enforcement of OSHA standards. A number of OSHA health standards apply to healthcare workers, including standards related to ethylene oxide, bloodborne pathogens, formaldehyde, ionizing radiation, hazard communication, and noise. OSHA also has several safety standards applicable to healthcare workplaces, including standards with requirements for respirators and gloves and other personal protective equipment, as well as standards to protect workers against slips, trips, and falls; fires; unkempt or unsanitary work areas; and compressed gases. (A searchable database of OSHA standards can be found here.)

There are still unregulated hazards that affect healthcare workers every day, such as infectious diseases (aside from bloodborne pathogens), workplace violence, back injuries, and numerous additional chemicals and drugs. Unfortunately, the process for issuing new OSHA standards is lengthy and difficult. On top of the requirements in the Occupational Safety and Health Act, four factors have added years, and sometimes decades, to the regulatory process envisioned by OSHA’s founders: court decisions, additional legal burdens imposed by Congress, decades of regulatory executive orders, and politics (because recent Republican administrations have rarely issued any OSHA standards).

The General Duty Clause

Where workers are faced with a hazard for which there is no OSHA standard (e.g., ergonomics, workplace violence, and most infectious diseases), the agency can use the General Duty Clause to cite employers for unsafe conditions.

The General Duty Clause is Section 5(a)(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which states that “Each employer shall furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees.”3 In order to cite under the General Duty Clause, the inspector must prove that there’s a serious hazard, that it’s a “recognized” hazard (for example, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or an industry authority), and that there is a feasible means of abatement—in other words, there’s something employers can do to eliminate or reduce the hazard.4

Citations using the General Duty Clause take more time and resources and are much more legally burdensome than citations using a specific standard. Consequently, there are relatively few OSHA citations for hazards involving ergonomics or workplace violence; of the 1,347 citations issued to healthcare and social assistance employers from October 2020 through September 2021, only 10 were for violations of the General Duty Clause.5

OSHA Inspections

OSHA’s main function is to enforce standards to ensure that employers provide a safe workplace. However, OSHA’s enforcement activities are restricted by its low funding and are subject to the political priorities of the presidential administration that oversees the agency.

In most cases, OSHA determines whether a standard has been violated by physically inspecting the workplace. OSHA cannot just arbitrarily inspect any workplace; there must be sufficient grounds to inspect. For example, if there is a fatality, a worker complaint, a report of a serious incident, or a referral from another agency or media report, OSHA can legally enter a workplace for an inspection. An employer has the right to refuse entrance, and OSHA must then get a court order to enter the workplace.6

A worker can request an inspection by filing a confidential, anonymous complaint on OSHA’s website (see here). Where there is a union, the union representative is allowed to file a complaint on behalf of the worker. Workers do not have to be certain there is an OSHA violation in order to file a complaint as long as they have a good-faith belief that the work is dangerous.7

Inspections are unannounced, with very few exceptions. They begin with an opening conference with the employer (and the union representative) and end with a closing conference to review the findings. In addition to participating in the opening and closing conferences, workers or their union representatives are allowed to walk around with the inspector during an inspection to ensure that the inspector understands how the work is done and what hazards the workers may be exposed to. Where there is no union, OSHA inspectors are supposed to speak with a representative number of workers.8

Under certain situations, OSHA can also do “programmed” inspections. These proactive inspections are conducted in high-risk workplaces or to address specific hazards even where there has been no complaint or incident. For example, OSHA has a number of temporary local and national emphasis programs that allow the agency to focus on particular hazards and on high-hazard industries.9 OSHA currently has national emphasis programs that cover COVID-19 and heat.10 In the past, it has had emphasis programs focused on workplace violence and nursing homes.

Following the initiation of an inspection, OSHA has six months to issue a citation for any violations discovered. Employers may be assessed penalties for violations that put employees at risk. OSHA’s penalties differ based on the type of violation cited; maximum penalties are set by law and are increased annually based on inflation. The current maximum penalty for a “serious” violation—a dangerous health or safety hazard that an employer knew or should have known about—is $14,502 per violation. The maximum penalty for a “willful” violation—when the employer demonstrates an intentional disregard for the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Act or a plain indifference to employee safety and health—is $145,020 per violation.

These penalties are generally negotiated down from the maximum. The average penalty for a serious violation, for example, is only around $4,000. For many employers, these penalties are far too low to be meaningful; even $145,020 would be an insignificant cost of doing business for large corporations. But for workers and their unions, OSHA’s citations can be powerful bargaining tools as executives seek to protect their corporations’ reputations.

OSHA is only able to pursue criminal charges where there has been a fatality associated with a willful violation. OSHA does not have the authority to shut down a workplace or operation unless there is an “imminent danger” where death or serious harm is threatened and could occur immediately.11

Other Worker Rights

In addition to the right to file a complaint and receive an inspection, OSHA provides a number of other rights to workers.12

Nondiscrimination: Section 11(c) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act prohibits employers from retaliating against workers for exercising their health and safety rights.13 Unfortunately, this language is antiquated and does not provide the same protections as more modern anti-retaliation laws. For example, workers must file a retaliation complaint within 30 days, far less time than the six months that many more recent laws provide.

Access to injury, illness, exposure, and medical records: Most employers are required to keep track of all injuries and illnesses, worker medical records, and chemical exposure data required by many OSHA standards. Workers have the right to request this information (and their own medical records), which can be useful to track patterns of injuries and illnesses in a workplace and to determine the effectiveness of the employer’s health and safety program.

Training about hazards: OSHA’s Hazard Communication Standard requires that employers provide training about the hazards of all chemicals they are exposed to and what can be done to protect employees from harm. Many individual OSHA standards also require training.

Compliance Assistance

OSHA provides information and training to support compliance with standards on a variety of health and safety topics. For example, OSHA has webpages covering healthcare in general,14 hospitals,15 COVID-19,16 safe patient handling (ergonomics),17 workplace violence,18 and infectious diseases.19

OSHA also runs the Susan Harwood Training Grant Program, which provides training funds to nonprofit institutions, including labor unions, universities, and other worker-oriented organizations. The grants can be used for training in healthcare hazards, ergonomics, communicable diseases, workplace violence, and other hazards.20

In addition, OSHA funds an Onsite Consultation program in all states that provides free inspections (“consultations”) to small and medium-size employers.21 These onsite consultations do not carry the risk of enforcement unless serious hazards are identified that the employer refuses to address.

–J. B.

*Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and the US Virgin Islands have public sector plans. (return to article)

†Public employees are not covered by OSHA in the District of Columbia or in the following states: Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “State Plan Frequently Asked Questions,” US Department of Labor.

2. B. Scott, “Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act: Report Together with Minority Views,” US House Committee on Education and Labor, 117th Congress, First Session, Rept. 117-14, Part 1, April 5, 2021.

3. OSHA Act of 1970, Pub. L. No. 91-596, 84 Stat. 1590 (1970).

4. R. Fairfax to M. Racic, “Elements Necessary for a Violation of the General Duty Clause,” US Department of Labor, OSHA, December 18, 2003.

5. OSHA, “NAICS Code: 62 Health Care and Social Assistance: Establishment Size: ALL Sizes,” US Department of Labor.

6. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “1903.4 - Objection to Inspection,” US Department of Labor, Federal Register 45 (October 3, 1980): 65923.

7. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Federal OSHA Complaint Handling Process,” US Department of Labor.

8. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Inspections,” OSHA FactSheet, August 2016.

9. “Chapter 2: Program Planning” in Field Operations Manual (Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, OSHA, April 14, 2020).

10. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Directives - NEP,” US Department of Labor.

11. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Imminent Danger,” US Department of Labor.

12. Worker’s Rights (Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, OSHA, 2019), OSHA 3021-12R.

13. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “1977.3 - General Requirements of Section 11(C) of the Act,” US Department of Labor.

14. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Healthcare,” US Department of Labor.

15. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for Our Caregivers,” US Department of Labor.

16. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19),” US Department of Labor.

17. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Healthcare: Safe Patient Handling,” US Department of Labor.

18. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Healthcare: Workplace Violence,” US Department of Labor.

19. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Healthcare: Infectious Diseases,” US Department of Labor.

20. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Susan Harwood Training Grant Program,” US Department of Labor.

21. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “On-Site Consultation,” US Department of Labor.

[Illustrations by Lucy Naland]