Black History Month at the AFT

As the United States marks its 250th anniversary this year, Black History Month offers an important opportunity to reflect honestly on the nation’s origins and the work still required to fulfill its democratic promise. Before becoming a phrase etched into history books, E Pluribus Unum (“Out of Many, One”) was the nation’s first guiding motto. Adopted in 1782 as part of the Great Seal of the United States, it reflected an aspiration that a nation could be formed from many people, cultures and communities united by shared democratic ideals. While the early promise of this vision was deeply limited by enslavement, exclusion and inequality, the phrase has endured as a statement of possibility that has been expanded and redefined through struggle.

It has been Black Americans, alongside other marginalized communities, who have pushed the nation closer to the meaning of E Pluribus Unum. From building the country’s physical infrastructure—including schools, hospitals, roads and public institutions—to shaping its civic and moral foundations through organized resistance, labor movements and civil rights advocacy, Black workers, educators, healthcare professionals and freedom fighters have been essential to the nation’s progress. Their labor built the country. Their organizing strengthened its democracy.

Today, that legacy continues through AFT members. As educators, healthcare workers and public employees, we stand on the frontlines of our communities and our democracy. As the AFT makes clear, our future should not be a choice between chaos, corruption and cruelty on one hand, and a broken status quo on the other. We fight for a better life that people can see, feel and afford. We refuse to stand by while public schools are abandoned, healthcare is stripped away, workers’ rights are attacked, and democracy itself is undermined for the benefit of the powerful.

Black History Month provides a vital opportunity to connect this moment of national reflection to the historical movements that made progress possible. The rights to organize, vote, learn and live with dignity were not freely given. They were won through collective action. A democracy that works for all is the foundation of economic opportunity, and strong public schools and public services remain the bedrock of our shared future.

By reclaiming E Pluribus Unum as a living framework during the nation’s 250th year, the AFT affirms that democracy is strongest when many voices are included and many communities are empowered. This Black History Month, the AFT elevates Black history as workers’ history, democracy’s history and America’s history, while reinforcing a simple truth. Honoring the past means continuing the work.

Watch Our Videos

AFT Voices

Rodney Fresh, a history teacher in Detroit, has seen firsthand what a high-quality education can do for his students, but Project 2025 would decimate much of the public education system that benefits his students, from Title I and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act to the African American history class he teaches—a favorite at his high school. Fresh shares his moving experiences in the classroom and warns against policies that could jeopardize all the good public education is able to bring to students who need our support.

AFT member Gemayel Keyes grew up attending Philadelphia public schools before he started his career there—first as a bus attendant, then a teaching assistant and, finally, a special education teacher. Keyes described his career trajectory—including the obstacles he faced—to a U.S. Senate committee June 20, urging legislators to support teacher pipelines and grow-your-own programs like the one he attended. The Para Pathways program was founded in part by Keyes’ union, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

Lois Lofton-Doniver, a Detroit educator, believes that nurses are invaluable not only for their medical expertise but also for their dedication, compassion and generosity to their patients, families and strangers in need. In her AFT Voices post, Lofton-Doniver expresses gratitude to the nurses who go above and beyond to provide much-needed care and comfort.

Ternesha Burroughs loves her job teaching high school math, but when student loans weighed her down and her salary just couldn’t keep up, she wondered if it might not be better to grab a job at the fast food restaurant down the street, where they were actually paying more. Many years later, Burroughs worked with her union and now she's thrilled that her loans have finally been canceled, but she worries about how student debt and low salaries contribute to the teacher shortage.

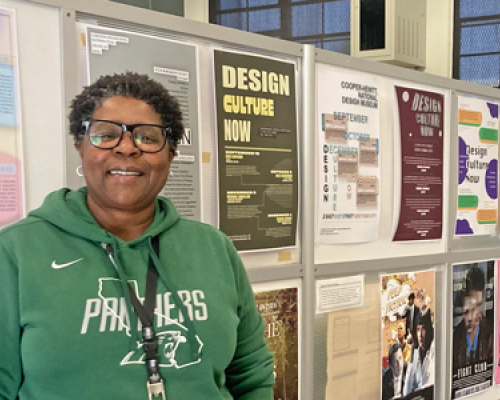

When Letecia Miller started teaching graphic arts in the Los Angeles school district, her school had substandard equipment and not much money to upgrade. But Miller had a vision, and after years of persistence she secured the grants she needed to build an impressive graphic design studio for her students. The effort, she says, was worth it: Career and technical education can be a powerful pathway for education in communities like hers.

AFT News

D.C.’s Walter E. Washington Convention Center was buzzing Sept. 11-15 at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Annual Legislative Conference, a much-anticipated celebration of Black excellence teeming with high-profile political celebrities, passionate activists, policymakers and advocates. Amid it all were AFT members mingling and mixing, not only claiming their niche at AFT-sponsored sessions on education and labor, but contributing to—and reveling in—the heady celebration of accomplishment, community and culture.

The award may have been kept secret, but it’s no secret that AFT President Randi Weingarten is a powerful advocate for women. On Tuesday, she received the AFT Women’s Rights Award for her remarkable life of activism. Then, during the Human Rights Luncheon, other AFT members and partners received Drum Major for Justice awards for their work in social justice, and a panel of experts strategized about electing Kamala Harris as our next president of the United States.

The White House marked the one-year anniversary of President Biden’s second executive order for Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government at an event Feb. 14, with a gathering of Cabinet members and deputies who enumerated the successes of the last two years and pledged to continue their work making government resources more accessible, more equitably, to the people who need them most. The order sweeps broadly over every level of government, improving access to education, entrepreneurship, veterans’ benefits, high-quality healthcare and more.

AFT members and affiliates were busy Feb. 5-9 during the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action, participating in everything from curriculum sharing sessions, film screenings, door decorating contests and classroom activities to underscore the principles of the movement. It was truly a demonstration of BLM at School’s aim: to commit to “a week of action, a year of purpose, a lifetime of practice.”

Journals

Although Hip Hop has long been misunderstood by many, it’s far more than just a musical genre. Hip Hop is a multifaceted form of expression that engages youth worldwide in processing their fears and joys, working through trauma and learning from each other’s experiences. As a social worker at a credit-recovery high school in the South Bronx, J.C. Hall founded the Hip Hop Therapy Studio program to provide culturally resonant treatment to youth through artistic media. In the Winter 2024-25 issue of American Educator, he shares the research behind his approach and how his students’ lives are being transformed.

Academic freedom encourages challenging discussions within class parameters and helps students and teachers alike grow and learn from each other, rather than merely confirming what they already believe—giving students the intellectual awakening that is key to a college education. In this American Educator article, Harvard Law professor Andrew Manuel Crespo explains how the freedom to teach is intrinsically connected to students’ freedom to learn, and what we risk by stifling healthy debate.

Youth activism is a powerful force behind significant social change in the United States. As students learn more about civic engagement and their power to make change, they are emboldened to confront the issues that matter to them and their communities—and to imagine a brighter future for all of us. The Fall 2024 American Educator shares resources available through Share My Lesson to inspire student learning and support student-driven activism.

Educational gag orders are chilling intellectual inquiry, discussion and expression on K-12 and higher education campuses. As professor and academic freedom scholar Michael Bérubé discusses in American Educator, these assaults are “taking the ‘educational’ part out of our educational institutions.” Bérubé describes how free speech absolutism and anti-shielding laws imperil students’ right to learn and explains the importance of bounded and focused classroom discussions.

As the vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union, Jackson Potter well knows the power of diverse community coalitions. But visiting a high school in Granite City, Ill., showed him that rural and urban locals alike can benefit from coalitions formed around meeting student and community needs. Using CTU’s Freedom School as an example, Potter explores how Granite City can build regional support to address its economic and environmental challenges, diversify its workforce and strengthen community connections. He also highlights the union’s role in fostering antiracist coalitions for educational and environmental justice.

What do a diabetic patient facing an unnecessary leg amputation, a child with worsening scalp ringworm and a feverish infant whose parents refuse immediate treatment have in common? They all need a clinician sensitive to their cultural contexts to advocate for their care. In the AFT Health Care journal, pediatrician and healthcare consultant Kimá Joy Taylor shares how diverse healthcare teams that are representative of their communities and provide culturally and linguistically effective care can improve patient outcomes and staff well-being.

A pediatrician and healthcare consultant probes into the healthcare-related barriers that prevent Black people from entering the healthcare professions, including healthcare-related trauma and history, the closing of Black-operated healthcare operations and racial segregation.

Share My Lesson blog posts

What does it mean to teach Black history 100 years after the first commemorations began? This milestone moment invites educators to reflect, reimagine and recommit to honoring Black voices in the classroom every day of the year.

Black influence shapes music, media, sports and technology. As we commemorate 100 years of Black history, how do we make sure students learn not just the impact but also who deserves the credit?

Raphael Bonhomme challenges teachers to move beyond seasonal lessons and embed Black history into the full American narrative. Through personal reflection and practical classroom examples—from Harlem Renaissance projects to lessons on Black Wall Street—this blog invites educators to rethink what students learn about history, identity and possibility.