Writing gives children a way to share their voices and ideas with the world. Even in early childhood, the purpose of writing is to communicate. All young children have messages to share, and writing is one tool they can use to communicate those messages. But even though the adults—from teachers to family members—who are caring for and educating young children value those messages, it is easy to miss early writing attempts because these do not look like conventional writing.1 For example, when children scribble, they are often writing, and drawing and writing are not always easy to distinguish. If we invite children to tell us about their work in open-ended ways (“Tell me about what you’ve made…” rather than “Did you draw your puppy?”), they may reveal that they have been writing (“I made my name!” or “It says happy birthday to mommy”). Once adults are attuned to children’s early attempts at written communication, there is much they can do to be supportive. While this article offers detailed guidance for preschool and prekindergarten teachers on early writing development, there are also simple steps teachers can share with family members, like inviting children to both write and dictate their messages and helping children use letters to label their drawings. But first, let’s break down what writing is and why it is so important.

There is strong agreement among researchers that writing includes both composition and transcription.2 Composition is the creative process in which writers identify the purposes of their messages, generate messages (including ideas and stories), and carefully select words to share them.3 For example, a preschooler might draw a red circle with a diagonal line through it and say, “This sign is so no one knocks down my tower.” Transcription—which includes handwriting and spelling—is the mechanical process that allows writers to represent their messages using established conventions (enabling others to understand them). For young children, handwriting focuses on learning how to make the shapes of letters (i.e., not on making perfect letters or writing letters on lines). Spelling refers to skills for matching letters to sounds in order to write words. As young children transition from scribbling to writing letters and words, they invent much of their spelling by writing the sounds they hear in words. Through explicit teaching of sound-spelling correspondences in which reading and writing are practiced together, children slowly learn standard academic spelling across the early childhood and elementary years.4

Even for college-educated adults who no longer have to devote much thought to the mechanics of writing, capturing their ideas in text is a complex task. For young children, it is quite challenging to form and remember messages while also figuring out how to put them on paper. Studies demonstrate that executive function skills, including self-regulation, are needed so that children attend to and persist in this complex task.5 Writing engages young children across developmental domains and activates motor, cognitive, and socioemotional learning.6

Why Is Early Writing So Important?

Young children (ages 3 to 5 years old) learn a lot from early writing opportunities. Early writing development predicts later reading and writing achievement.7 Moreover, young children tend to enjoy writing, particularly within the context of meaningful opportunities to express their ideas.8 So, what exactly do young children learn when they engage in writing?

Children learn the importance of communicating ideas through written text and images. When children engage in composing, they learn about meaningful purposes for writing and begin to understand the relationship between oral and written language. Consider 3-year-old Jaylen, who is eager to perform music in his classroom’s pretend theater and needs an audience. His teacher, Ms. Lopez, encourages Jaylen to make an invitation to his show. “You can write down your message to invite others to your performance,” she tells him, providing a purpose for his writing. She asks Jaylen to verbalize what he wants to tell his classmates about his show. Jaylen says, “I play music. Drums. Pretty music. They can listen or play.” Ms. Lopez offers encouraging feedback by saying, “That’s an important message. It tells others what you will do and what they can do.”

Recognizing Jaylen’s message is long, Ms. Lopez condenses it, suggesting, “So you want to say, ‘Music today, listen or play.’ ” Jaylen corrects her: “Pretty music.” Appreciating Jaylen’s attention to word selection, Ms. Lopez revises her suggestion, saying, “Pretty music today, listen or play.” Smiling to signal his approval, Jaylen writes some scribbles on the page along with his name and a picture of a drum. He “reads” his message aloud—an indication that he recognizes that his print has meaning—saying, “I play pretty music, you can listen or play.” Ms. Lopez reinforces the relationship between verbal and written language by stating, “Jaylen, you wrote the words you said. Now, use your invitation to invite the class to your show.”

While Jaylen did not write conventionally (i.e., he did not use letters to spell words), this example illustrates how he used oral language to compose his message, considered word selection, and recognized that print has meaning. In addition, Ms. Lopez provided a purpose for his writing, helped him to revise his message, and reinforced the relationships between oral and written language.

Children learn how text works, including foundational concepts like letter-sound relationships. Young children’s writing attempts are opportunities to practice and to extend what they know about how written text works. Even before young children can write letters, they might create rows of scribbles when making a grocery list or write a few letter-like shapes to make a sign. These writing attempts provide insights into what children know about writing for different purposes, starting long before they learn about letters and sounds.

Now consider Tamara, a 4-year-old who picks up a marker and draws a big red circle. Tamara says the word stop quietly to herself several times, then says “ssssssssss” as she slowly writes a backward S inside the circle. Working through the rest of the word, she says “sto… p, sto… p, p, p,” as she writes a P. Tamara then cuts out the shape and brings it over to the trucks she has been racing with friends to use in their play. She says, “OK, you got to make your truck stop right here,” as she places her stop sign on the floor.

This brief writing event tells us so much about Tamara’s literacy learning. She has noticed that print in the environment (e.g., a stop sign) has meaning, which is an important print concept for young children. She understands print as being useful and meaningful to others. She understands that we write words with letters, and she is attempting to form letters even if she does not yet understand that letters must face a particular direction. She knows that words in oral language can be broken into individual sounds (i.e., she is developing phonemic awareness*). Tamara’s phonemic awareness is evident when she tries to figure out the sounds in the word stop. She can represent the /s/ sound with the letter S and the /p/ sound with the letter P, demonstrating an understanding that letters represent sounds (i.e., the alphabetic principle) and of particular letter-sound relationships. In creating her stop sign, Tamara provides a rich example of how and why opportunities for writing in early childhood are associated with the development of print concepts, phonological awareness, and letter knowledge,9 which are all foundational skills10 for both reading and writing.

Intentional Supports for Early Writing

Recent research indicates that most preschools could offer far more opportunities for children to write for communication.11 One potential topic for professional development is how early childhood educators conceptualize writing. If teachers understand writing as only a spelling and handwriting task,12 they may not recognize opportunities for children to use writing like Jaylen and Tamara did—to share their messages—and to enhance their literacy development while engaging in other activities. In our recent research interviewing a diverse group of preschool teachers, we found that very few educators articulated beliefs or reported practices that centered writing instruction on encouraging children to compose their own messages, share their ideas, or otherwise make meaning.13 We also found that very few teachers used writing to support broader literacy learning. For example, even though almost all teachers had writing centers and activities in their classrooms, they tended to focus on name writing and letter formation; only about a fifth of the teachers allowed children to take writing materials into other spaces so that writing could be part of their play. For us, a big takeaway from the study is that early childhood educators would benefit from opportunities to reconsider the many ways that early writing reinforces fundamental literacy goals (like developing young children’s concepts of print) and encourages children to share their thoughts.

Research has found that children in classrooms where early educators support composition and meaning making demonstrate more advanced writing at the end of preschool than children in classrooms where only handwriting and spelling are supported.14 Clearly, when opportunities for meaningful writing exist, young children learn a lot! Here, we describe several research-based ways for preschool and prekindergarten teachers to intentionally support meaningful early writing opportunities for children.

Provide and draw attention to writing materials and environmental print resources. Young children benefit from classroom environments that are filled with writing materials and environmental print supports (e.g., signs in the classroom that pair text and images).15 Classrooms that are designed to support young writers have varied and plentiful opportunities for children to see print. But merely having the materials in the room is not enough. Print or writing materials in the environment do not support children’s learning if they are not both purposeful and used by children regularly; teachers must explicitly show children how to use these materials and create meaningful opportunities for using them.16

Teachers can promote children’s writing by providing various writing instruments—crayons, pencils, markers, chalk—and surfaces to write on—paper, dry-erase boards, chalkboards. Making plentiful and varied materials available communicates the importance of writing. These materials motivate young children to write and support their motor development as they learn to hold and press a number of different writing utensils.

Writing materials and other print resources should be available in a dedicated writing area that children can frequent during free-choice times, and they should be placed throughout the room in meaningful ways. For example, writing implements like paper, pencils, washable markers, and clipboards can be added to any dramatic play area. That way, students can act out how adults use writing within various roles (e.g., people working in stores write on order forms and price tags, and forest rangers write on trail maps and wildlife logs). Science and math areas are enhanced by including opportunities for recording data and measurements on graph and chart paper or in journals. Unlined paper in the library may prompt children to write about the books they read or make their own books. To encourage writing and support children’s developing letter-sound knowledge, an alphabet chart with images reflecting the sounds that each letter represents should be prominently displayed at children’s eye level to support their writing.

Teachers must explicitly support young children in using these print resources. For example, a teacher might reference the alphabet chart to help a child write the word mom when composing a letter. “Which letter on the chart makes the mmm sound like mmmom? I see you are pointing to the M. On the chart, there is a picture of the moon next to M. Mom and moon both start with the mmm sound, and we make that with an M.” Other print resources that can be referenced daily are the class schedule, a snack or lunch menu, or a sign-in sheet.

Accept and encourage writing attempts. Children’s early writing attempts, including scribbles or letter-like forms, lay an important foundation for writing letters. When teachers encourage any form of writing, they show that children’s ideas are valued and help children to see themselves as writers, to participate in writing before they have well-developed motor or spelling skills, and to understand the connection between oral language and print.

Teachers play a huge role in young children’s writing by nurturing their efforts. But before teachers can celebrate children’s efforts to communicate through print, they need to intentionally look for and learn to quickly recognize children’s early writing. Children’s writing attempts may look different depending on their home language and their previous exposure to writing at home and school. For bilingual children, writing attempts in both home and school languages should be accepted and encouraged. This includes children’s attempts to write words in their home languages as well as their use of the written symbols of these languages. For example, children who see written Chinese or Arabic in their homes may try to write symbols that look like the orthography of these languages.17 Learning to recognize everything from the earliest scribbles to attempts to form Cantonese characters is challenging. Fortunately, young children tend to be very receptive to open-ended inquiries about their work. For a scribble that could be a drawing or writing, a teacher could say, “You are creating many different lines. Tell me about these lines.” For children with less expressive language, you might ask them to point to or show you what they are making. For a piece that is clearly writing but is not decipherable, a teacher could say, “I see that you are writing. Tell me about your message.”

Because preschool and prekindergarten classrooms tend to include children with a wide range of writing skills and experiences, teachers can create writing opportunities that allow children to participate in varied ways. When choosing a beverage for mealtime, for example, children could have options for responding to the question “Do you want water, juice, or milk?,” such as recording a tally, creating letter-like forms, or writing letters. For dual language learners, providing various scaffolds (and appreciating where children are developmentally in each language) can support bilingual children in communicating ideas in writing. For example, when the class is writing a thank-you note, the teacher can draw attention to the varied ways in which we write thank you by saying, “You can write gracias if you want to say thank you in Spanish.” Explicitly valuing children’s home languages† not only supports bilingual children’s learning but also strengthens monolingual children’s orthographic knowledge by highlighting how different languages represent oral language in different ways.

Connect writing to thematic units and children’s play. Early childhood teachers have a unique opportunity to connect writing experiences to curricular units in ways that deepen children’s interest in writing, help children understand the varied purposes for generating and recording ideas, and create opportunities to share content knowledge. For young children, purposeful writing-related interactions occur when writing becomes part of play—thus allowing teachers to support and engage children in writing instruction that is meaningful to their interests and development.18

Opportunities to write across genres within a thematic unit of play include communicating information to others (informational), telling others how to do something (procedural), or convincing others that something is important (persuasive).19 If children create a restaurant, for example, they may write a menu to inform diners of their options, write recipes to show how dishes on the menu should be prepared, and write an advertisement explaining why their restaurant uses locally grown ingredients.

As children learn about a theme or topic, the goal is to show children real ways adults use writing to communicate in their daily lives. For example, during a unit on pets, Mr. Patel sets up an animal hospital play center. The setting allows children to

- record injuries and illnesses on animal health charts,

- label animals and their body parts using word cards with pictures,

- write their names on checkout cards to take care of animals,

- record things that the animals need (e.g., Have they been fed? Have they been groomed? Have they been walked or cuddled?), and

- generate and write (or draw) fliers persuading others to adopt a pet.

Mr. Patel uses the animal hospital to facilitate children’s self-directed play and to base whole-group instruction on children’s interests. For instance, Mr. Patel watches as Lily explains to Mason that her cat hurt its tail and needs the veterinarian’s help. After Mason circles the tail on a cat picture, Mr. Patel helps them write “hrt tal” and asks if they would like to post this writing on the class meeting board for later in the day when the class will discuss and write steps informing others about how to care for animals. Lily and Mason agree, and soon they are getting the other children excited about helping Lily’s cat during their group time.

Provide multiple ways for children to participate in interactive writing. Interactive or shared writing, a strategy in which both the teacher and the child participate in “sharing the pen,” is an important way to promote early writing.20 During interactive writing, the teacher intentionally capitalizes on what individual children can contribute to engage them in learning about writing and literacy.

It’s beneficial to intentionally engage children’s oral language and print knowledge skills through interactive writing. To promote oral language, teachers can ask a child to say aloud their message as the teacher records the child’s words. To expand the experience, the teacher can ask questions while they write together to encourage the child to add more details. To enhance vocabulary, teachers can offer new or alternative word selections. For example, “Do you want to write about a friendly or a fierce monster?” And to solidify the relationship between oral and written language, teachers can prompt children to read their message aloud.

To support knowledge of print concepts, such as sentences are made of words and words are separated by spaces, teachers can prompt children to count the number of words in their message and then draw a line to represent each word. Teachers can then prompt children to identify sounds in the words in their message and figure out which letters represent these sounds. Children can record the letters they know, and the teacher can fill in the rest. As children learn more about letters and sounds, they can do more of the writing with less teacher support. Young children are excited to read back the words they have written.

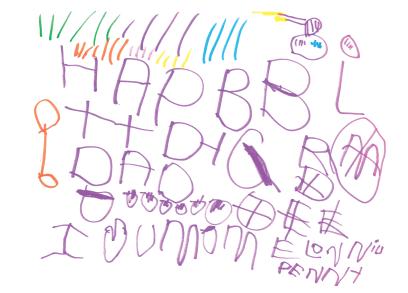

Observe children’s writing to inform instruction. Children’s writing tells us a lot about what children want to say, what sparks their interest, and what they know about how print works and about different types of writing. For example, a child who writes “Mom” on the top of the page, draws a heart in the middle, and signs their name at the bottom of the page knows something about writing a letter. A child who scribbles on a notepad as they take an order from a customer in the classroom restaurant recognizes that language can be recorded and that print has meaning. A child who writes a string of letters from left to right and continues on the line below demonstrates understanding of the directionality and linearity of print. A child who writes “Hpe Bd” on a Happy Birthday card for a classmate demonstrates knowledge of some letter-sound relationships.

Children vary widely in their writing development from ages 3 to 5. Therefore, teachers can examine children’s writing artifacts to identify what they know and do not yet know about writing and print. This knowledge can be used to individualize writing support.21 That is, for children who draw and scribble, teachers can direct their attention to written text in books and on signs to encourage the use of print in addition to their drawings. For children writing letter strings (i.e., letters without associations to sounds), teachers can teach letter-sound relationships and prompt children to identify and record initial sounds in words. Children who write letters to represent the first sounds in words can be encouraged to write letters reflecting more of the sounds they hear.

When young children are recognized as writers, their ideas are acknowledged as valuable and their writing attempts provide opportunities to support their developing language and literacy skills. Children’s writing also lets teachers observe children’s developing understandings about literacy in order to teach what children need to learn next.

Imagine a preschool classroom where children have regular opportunities to engage in early writing with support from adults who provide writing materials, draw children’s attention to print and its purposes, express genuine interest in and ask questions about their ideas as they write, help children to segment the sounds in words they want to write, and show children how to form letters that represent those sounds. For children, the focus is on communicating. For teachers, these writing experiences also provide meaningful opportunities to strengthen children’s critical early literacy skills and to ensure that all children feel that their ideas are worthy of sharing.

Hope K. Gerde is a professor in the Department of Teaching, Learning & Culture at Texas A&M University and a former preschool teacher. Tanya S. Wright is an associate professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Michigan State University and a former kindergarten teacher. Gary E. Bingham is a professor in the Department of Early Childhood and Elementary Education and the director of the Urban Child Study Center at Georgia State University, and a former preschool teacher.

*For more on phonemic awareness and effective literacy instruction, see “Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science” in the Summer 2020 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

†For more on celebrating students’ home languages and linguistic strengths, see “Bilingualism and Biliteracy for All” in the Summer 2020 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. A. H. Hall et al., “Who Counts as a Writer? Examining Child, Teacher, and Parent Perceptions of Writing,” Early Child Development and Care 189 (2019): 353–75.

2. V. W. Berninger and W. D. Winn, “Implications of Advancements in Brain Research and Technology for Writing Development, Writing Instruction, and Educational Evolution,” in Handbook of Writing Research, ed. C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, and J. Fitzgerald (New York: Guilford Press, 2006), 96–114; Y.-S. G. Kim, “Interactive Dynamic Literacy Model: An Integrative Theoretical Framework for Reading-Writing Relations,” in Reading-Writing Connections Towards Integrative Literacy Science, ed. R. Alves, T. Limpo, and R. M. Joshi (Springer, 2020), 11–34; and C. S. Puranik and C. J. Lonigan, “Emergent Writing in Preschoolers: Preliminary Evidence for a Theoretical Framework,” Reading Research Quarterly 49 (2014): 453–67.

3. D. W. Rowe, “The Social Construction of Intentionality: Two-Year-Olds’ and Adults’ Participation at a Preschool Writing Center,” Research in the Teaching of English 42 (2008): 387–434.

4. N. K. Duke and H. A. E. Mesmer, “Phonics Faux Pas: Avoiding Instructional Missteps in Teaching Letter-Sound Relationships,” American Educator 42 (Winter 2018–2019): 12–16.

5. Berninger and Winn, “Implications of Advancements”; and C. S. Puranik, E. Boss, and S. Wanless, “Relations Between Self-Regulation and Early Writing: Domain Specific or Task Dependent?,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 46 (2019): 228–39.

6. H. K. Gerde et al., “Child and Home Predictors of Children’s Name Writing,” Child Development Research (2012): 1–12.

7. D. Aram, “Continuity in Children’s Literacy Achievements: A Longitudinal Perspective from Kindergarten to School,” First Language 25 (2005): 259–89; and Y-S. G. Kim, S. Al Otaiba, and J. Wanzek, “Kindergarten Predictors of Third Grade Writing,” Learning and Individual Differences 37 (2015): 27–37.

8. C. Zhang and M. F. Quinn, “Preschool Children’s Interest in Early Writing Activities and Perceptions of Writing Experience,” Elementary School Journal 121 (2020): 52–74.

9. K. E. Diamond, H. K. Gerde, and D. R. Powell, “Development in Early Literacy Skills During the Pre-Kindergarten Year in Head Start: Relations Between Growth in Children’s Writing and Understanding of Letters,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23 (2008): 467–78.

10. H. A. E. Mesmer, “There Are Four Foundational Reading Skills. Why Do We Only Talk About Phonics?,” Education Week, January 23, 2020.

11. G. E. Bingham, M. Quinn, and H. K. Gerde, “Examining Early Childhood Teachers’ Writing Practices: Associations Between Pedagogical Supports and Children’s Writing Skills,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 39 (2017): 35–46.

12. S. A. Colby and J. N. Stapleton, “Preservice Teachers Teach Writing: Implications for Teacher Educators,” Reading Research and Instruction 45 (2006): 353–76.

13. H. K. Gerde, T. S. Wright, and G. E. Bingham, “Preschool Teachers’ Beliefs About and Instruction for Writing,” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 40 (2019): 326–51.

14. Bingham, Quinn, and Gerde, “Examining Early Childhood.”

15. H. K. Gerde, G. E. Bingham, and M. Pendergast, “Reliability and Validity of the Writing Resources and Interactions in Teaching Environments (WRITE) for Preschool Classrooms,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 31 (2015): 34–46.

16. C. Vukelich, “Effects of Play Interventions on Young Children’s Reading of Environmental Print,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 9 (1994): 153–70; and H. K. Gerde, M. E. Goetsch, and G. E. Bingham, “Using Print in the Environment to Promote Early Writing,” The Reading Teacher 70 (2016): 283–93.

17. C. Zhang et al., “Untangling Chinese Preschoolers’ Early Writing Development: Associations Among Early Reading, Executive Functioning, and Early Writing Skills,” Reading and Writing 33 (2020): 1263–94.

18. C. Neitzel, J. M. Alexander, and K. E. Johnson, “Children’s Early Interest-Based Activities in the Home and Subsequent Information Contributions and Pursuits in Kindergarten,” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (2008): 782–97.

19. N. K. Duke et al., “Authentic Literacy Activities for Developing Comprehension and Writing,” The Reading Teacher 60 (2006): 344–55.

20. S. Craig, “The Effects of an Adapted Interactive Writing Intervention on Kindergarten Children’s Phonological Awareness, Spelling, and Early Reading Development,” Reading Research Quarterly 38 (2003): 438–40; and A. H. Hall et al., “Exploring Interactive Writing as an Effective Practice for Increasing Head Start Students’ Alphabet Knowledge Skills,” Early Childhood Education Journal 42 (2014): 423–30.

21. S. Q. Cabell, L. S. Tortorelli, and H. K. Gerde, “How Do I Write ... ? Scaffolding Preschoolers’ Early Writing Skills,” The Reading Teacher 66 (2013): 650–59.

[Photo courtesy of the authors; illustrations by Penny Lishansky and Zora Gonzalez]