Increasing economic inequality and residential segregation have triggered a resurgence of interest in community schools—a century-old approach to making schools places where children can learn and thrive, even in underresourced and underserved neighborhoods. Community schools represent a place-based strategy in which schools partner with community agencies and allocate resources to integrate a focus on academics, health and social services, and youth and community development, and also foster community engagement.1 Many operate on all-day and year-round schedules, and serve both children and adults.

Although this strategy is appropriate for students of all backgrounds, many community schools arise in neighborhoods where structural forces linked to racism and poverty shape the experiences of young people and erect barriers to learning and school success. These are communities where families have few resources to supplement what typical schools provide.

Here we chronicle the history of community schools and identify the common features, or “pillars,” that are associated with high-quality community schools.* This article is drawn from “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence,” a report that examined 143 research studies (including 49 reviews of research) on community school characteristics, along with evaluation studies of community schools as a comprehensive strategy.† For each pillar, we synthesized high-quality studies that used a range of research methods, drawing conclusions about the findings that warrant confidence while also pointing to areas in which the research remains inconclusive.

A Brief History of Community Schools as a Response to Poverty and Inequality

Educators, community leaders, and advocates have long viewed community schools as a powerful, comprehensive response to the needs of neighborhoods experiencing poverty and racial isolation. The approach can be traced back to early 20th-century efforts to make urban schools “social centers” serving multiple social and civic needs.2 With increasing industrialization, immigration, and urbanization, the socioeconomic shifts of the late 19th century created new roles for public institutions to address the needs of the urban poor. Social reformers looked to schools to be social centers that could help address these needs, teach what the reformers deemed “wholesome” community values and proper hygiene, and act as sites for open discussion with people from various class backgrounds and political orientations.

The next wave of support for community schooling came in the 1930s, as social reconstructionists sought to give schools a critical role in addressing the social upheaval of the Great Depression. They believed the crisis called for new economic and political structures and large programs to relieve poverty. Drawing on the ideas of John Dewey, America’s foremost education philosopher, community schooling proponents sought to create a strong social fabric, preserve American democracy, and strengthen struggling communities through democratic, community-oriented approaches to education.3 Schools, such as Franklin High in East Harlem, New York, acted as centers for community life that could support the well-being of the entire community while embracing the principles of democratic community-based inquiry that would help shape local ideas and politics.4 For example, students at Franklin conducted neighborhood surveys to assist the neighborhood’s campaign for more public housing. However, growing conservatism in the following decades largely undermined such progressive approaches.

Community schooling also has its roots in African American struggles for quality education and local control that sought to create more positive school-community relations.5 Under both de jure and de facto segregation, schools for African American children functioned as important social hubs controlled by and serving the black community, with broad-based participation, collaborative relations, and shared experiences and attempts to mitigate economic hardships and violence from white supremacists. The James Adams Community School is one example of a school rooted in this history. Between 1943 and 1956, this segregated school located in Pennsylvania served black students in grades K–9 by day and operated as a community center by night, offering free activities and classes for students, families, and community members. Its existence challenged the belief that black students were inferior, as the school and community worked together to create activities, curriculum, and community-based learning opportunities that were both challenging to and supportive of the students.6

The 1960s and 1970s brought a resurgence of community schooling. Advocacy groups saw these institutions as a way to build power by improving learning and addressing social issues,7 including largely segregated and underfunded schools in urban centers that were not providing quality education to students.8 Interest in community schooling also increased as a response to desegregation, as students of color bore the brunt of desegregation efforts and faced discrimination in their new schools. Community control of the schools represented a chance to remedy the downward spiral of urban education, make schools accountable to low-income black parents the way they were to parents in suburban schools,9 promote democracy through wide-scale participation, and challenge discriminatory practices.10 These initiatives struggled from lack of political support, insufficient funding, and opposition from some teachers who worried that community control threatened their professional responsibilities and standing.11

Like their predecessors, today’s community schools build partnerships between the school and other local entities—higher education institutions, government health and social service agencies, community-based nonprofits, and faith-based organizations. These partnerships intentionally create structures, strategies, and relationships to provide the learning conditions and opportunities—both in school and out—that are enjoyed by students in better-resourced schools, where the schools’ work is supplemented by high-capacity communities and families. Like much of American education, today’s community schools focus more on meeting the individual needs of students and families (in terms of health, social welfare, and academics) than the earlier emphasis on strengthening communities or civil society more generally. However, the most comprehensive community schools today also seek to be social centers where neighbors come together to work for the common good.12

Community schools cannot overcome all problems facing poor neighborhoods—that would require substantial investments in job training, housing and social safety net infrastructures, and other poverty alleviation measures. However, they have a long history of connecting children and families to resources, opportunities, and supports that foster healthy development and help offset the harms of poverty. A health clinic can deliver medical and psychological treatment, as well as glasses to myopic children, dental care to those who need it, and inhalers for asthma sufferers. Extending the school day and remaining open during the summer enable the school to offer additional academic help and activities, such as sports and music, which can entice youngsters who might otherwise drop out. Community schools can engage parents as learners as well as partners, offering them the opportunity to develop a skill, such as learning English or cooking, or preparing for a GED or citizenship exam, and this approach can support their efforts to improve the neighborhood—for example, by securing a stop sign or getting rid of hazardous waste.13

Common Features of Community Schools

The Coalition for Community Schools defines community schools as “both a place and a set of partnerships between the school and other community resources, [with an] integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, and community engagement.”14 These partnerships enable many community schools to be open year-round, from dawn to dusk, six days a week, becoming neighborhood hubs where community members have access to resources that meet family needs and are able to engage with educators. This contrasts sharply with a “no excuses” approach in which schools that deliver high-quality instruction in a high-expectation culture are expected to surmount barriers imposed by poverty. Rather, community schools focus simultaneously on providing high-quality instruction and addressing out-of-school barriers to students’ engagement and learning.

The community schools approach is not a program, in the sense of specific structures and practices that are replicated across multiple contexts. Rather, it is grounded in the principle that all students, families, and communities benefit from strong connections between educators and local resources, supports, and people. These strong connections support learning and healthy development both in and out of school and help young people become more confident in their relations with the larger world. In distressed communities, this general principle takes on heightened urgency, as educators and the public recognize that conditions outside of school must be improved for educational outcomes to improve, and that, reciprocally, high-quality schools are unlikely to be sustained unless they are embedded in thriving communities.15

In any locality, educators developing community schools operationalize these principles in ways that fit their context, linking schools to like-minded community-based organizations, social service agencies, health clinics, libraries, and more. They take full advantage of local assets and talent, whether it is a nearby university, the parent who coaches the soccer team, the mechanic who shows students how to take apart an engine, the chef who inspires a generation of bakers, or the artist who helps students learn how to paint. Not only do student needs and community assets differ across contexts, so does the capacity of the local school system. Not surprisingly, then, community schools vary considerably from place to place in their operation, their programmatic features, and, in some cases, their theories of school improvement.

Some schools coordinate with health, social, or other educational entities to provide services on a case-by-case basis in response to the needs of students and their families. Others work with service providers to integrate a full range of academic, health, and social services into the work of the school and make them available to all students, a strategy often called “wraparound” services.

Some schools complement their provision of services for students, families, and communities with practices that bring community and family voices into governance, treating families as partners rather than as clients. Still others engage with partners in economic development, community organizing, and leadership development of community members, and also offer learning opportunities and social supports to parents and students.16 This diversity is evident in the array of names that various community school initiatives use to identify their work, including school-linked services, school-based services, full-service community schools, school-community partnerships, and the StriveTogether initiatives, among others.17

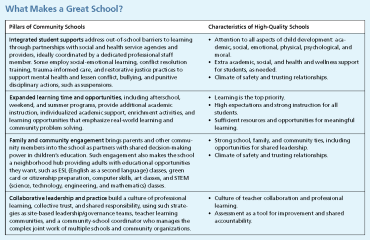

Notably, however, our comprehensive review of community schools research identified common features that are found in different types of community schools. These four features, or community school pillars, include (1) integrated student supports, (2) expanded learning time and opportunities, (3) family and community engagement, and (4) collaborative leadership and practice.

Integrated student supports, or wraparound services, such as dental care or counseling for children and families, are often considered foundational. Expanded learning time and family engagement are also common programmatic elements. Collaborative leadership can be viewed as both a programmatic element and an implementation strategy. The synergy among these pillars is what makes community schools an identifiable approach to school improvement: the pillars support educators and communities to create good schools, even in places where poverty and isolation make that especially difficult.

The four pillars are fundamental to the success of community schools. Individually and collectively, they serve as scaffolds (or structures, practices, or processes) that support schools to instantiate the conditions and practices that enhance their effectiveness and help them surmount the barriers to providing high-quality learning opportunities in low-income communities. These pillars increase the odds that young people in low-income and underresourced communities will be in educational environments with meaningful learning opportunities, high-quality teaching, well-used resources, additional supports, and a culture of high expectations, trust, and shared responsibility. Such features are associated with high-quality schools in more affluent and well-connected communities, where local institutions, family resources, and the social capital of community members complement what the local schools can provide.

The conditions that these pillars enable are those that decades of research have identified as school characteristics that foster students’ intellectual, social, emotional, and physical development. A skillful teacher, a challenging curriculum, and supports for both students and teachers form the starting point. Join these elements, and evidence shows that real learning—academic, physical, and social-emotional—will take place.18

The table below shows the high-quality school conditions and practices that the four community school pillars scaffold.

In sum, community school pillars are the mediating factors through which schools achieve good outcomes for students. The extent to which a community school is likely to create these conditions will depend, of course, on the emphasis it places on particular pillars and the quality of their implementation.

Findings from Our Review of the Research

We find that well-implemented community schools lead to improvement in student and school outcomes and contribute to meeting the educational needs of low-achieving students in high-poverty schools. Specifically, our analyses produced 12 findings:‡

- Finding 1. The evidence base on community schools and their pillars justifies the use of community schools as a school improvement strategy that helps children succeed academically and prepare for full and productive lives.

- Finding 2. Sufficient evidence exists to qualify the community schools approach as an evidence-based intervention under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (i.e., a program or intervention must have at least one well-designed study that fits into its four-tier definition of evidence).

- Finding 3. The evidence base provides a strong warrant for using community schools to meet the needs of low-achieving students in high-poverty schools and to help close opportunity and achievement gaps for students from low-income families, students of color, English learners, and students with disabilities.

- Finding 4. The four key pillars of community schools promote conditions and practices found in high-quality schools and address out-of-school barriers to learning.

- Finding 5. The integrated student supports provided by community schools are associated with positive student outcomes. Young people receiving such supports, including counseling, medical care, dental services, and transportation assistance, often show significant improvements in attendance, behavior, social functioning, and academic achievement.

- Finding 6. Thoughtfully designed expanded learning time and opportunities provided by community schools—such as longer school days and academically rich and engaging afterschool, weekend, and summer programs—are associated with positive academic and nonacademic outcomes, including improvements in student attendance, behavior, and academic achievement.

- Finding 7. The meaningful family and community engagement found in community schools is associated with positive student outcomes, such as reduced absenteeism, improved academic outcomes, and student reports of more positive school climates. Additionally, this can increase trust among students, parents, and staff, which in turn has positive effects on student outcomes.

- Finding 8. The collaborative leadership, practice, and relationships found in community schools can create the conditions necessary to improve student learning and well-being, as well as improve relationships within and beyond the school walls. The development of social capital and teachers learning from their peers appear to be the factors that explain the link between collaboration and better student achievement.

- Finding 9. Comprehensive community school interventions have a positive impact, with programs in many different locations showing improvements in student outcomes, including attendance, academic achievement, high school graduation rates, and reduced racial and economic achievement gaps.

- Finding 10. Effective implementation and sufficient exposure to services increase the success of a community schools approach, with research showing that longer-operating and better-implemented programs yield more positive results for students and schools.

- Finding 11. Existing cost-benefit research suggests an excellent return on investment of up to $15 in social value and economic benefits for every dollar spent on school-based wraparound services.

- Finding 12. The evidence base on comprehensive community schools can be strengthened by well-designed evaluations that pay close attention to the nature of the services and their implementation.

Research-Based Lessons for Policy Development and Implementation

Community school strategies hold considerable promise for creating good schools for all students, but especially for those living in poverty. Based on our analysis of this evidence, we identified 10 research-based lessons for guiding policy development and implementation:

- Lesson 1. Integrated student supports, expanded learning time and opportunities, family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership practices appear to reinforce each other. A comprehensive approach that brings all of these factors together requires changes to existing structures, practices, and partnerships at school sites.

- Lesson 2. In cases where a strong program model exists, implementation fidelity matters. Evidence suggests that results are much stronger when programs with clearly defined elements and structures are implemented consistently across different sites.

- Lesson 3. For expanded learning time and opportunities, student access to services and the way time is used make a difference. Students who participate for longer hours or a more extended period receive the most benefit, as do those attending programs that offer activities that are engaging, are well aligned with the instructional day (i.e., not just homework help, but content to enrich classroom learning), and address whole-child interests and needs (i.e., not just academics).

- Lesson 4. Students can benefit when schools offer a spectrum of engagement opportunities for families, ranging from providing information on how to support student learning at home and volunteer at school, to welcoming parents involved with community organizations that seek to influence local education policy. Doing so can help in establishing trusting relationships that build upon community-based competencies and support culturally relevant learning opportunities.

- Lesson 5. Collaboration and shared decision making matter in the community schools approach. That is, community schools are stronger when they develop a variety of structures and practices (e.g., leadership and planning committees, professional learning communities) that bring educators, partner organizations, parents, and students together as decision makers in the development, governance, and improvement of school programs.

- Lesson 6. Strong implementation requires attention to all elements of the community schools model and to their placement at the center of the school. Community schools benefit from maintaining a strong academic improvement focus, and students benefit from schools that offer more intense or sustained services. Implementation is most effective when data are used in an ongoing process of continuous program evaluation and improvement, and when sufficient time is allowed for the strategy to fully mature.

- Lesson 7. Educators and policymakers embarking on a community schools approach can benefit from a framework that focuses on creating school conditions and practices characteristic of high-performing schools and ameliorating out-of-school barriers to teaching and learning. Doing so will position them to improve outcomes in neighborhoods facing poverty and isolation.

- Lesson 8. Successful community schools do not all look alike. Therefore, effective plans for comprehensive place-based initiatives leverage local assets to meet local needs, while understanding that programming may need to be modified over time in response to changes in the school and community.

- Lesson 9. Strong community school evaluation studies provide information about progress toward hoped-for outcomes, the quality of implementation, and students’ exposure to services and opportunities. The impact that community schools have on neighborhoods is also an area that could be evaluated. In addition, quantitative evaluations would benefit from including carefully designed comparison groups and statistical controls, and evaluation reports would benefit from including detailed descriptions of their methodology and the designs of the programs.

- Lesson 10. The field would benefit from additional academic research that uses rigorous quantitative and qualitative methods to study both comprehensive community schools and the four pillars. Research could focus on the impact of community schools on student, school, and community outcomes, as well as seek to guide implementation and refinement, particularly in low-income, racially isolated communities.

While we may call for additional research and stronger evaluation, evidence in the current empirical literature clearly shows what is working now. The research on the four pillars of community schools and the evaluations of comprehensive interventions, for example, shine a light on how these strategies can improve educational practices and conditions and support student academic success and social, emotional, and physical health.

As states, districts, and schools consider the best available evidence for designing improvement strategies that support their policies and priorities, the effectiveness of community school approaches offers a promising foundation for progress.

Anna Maier is a research and policy associate at the Learning Policy Institute (LPI). Julia Daniel is a doctoral candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder. Jeannie Oakes is a senior fellow in residence at the LPI and a fellow at the National Education Policy Center. Livia Lam previously served as the senior policy advisor for the LPI and is now the legislative director for U.S. Senator Patty Murray. This article was excerpted with permission from their 2017 report, Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence. The authors wish to thank LPI senior fellow David Kirp for his thoughtful assistance with the report.

*For more on how partnerships connect communities and schools, see “Where It All Comes Together” and “Cultivating Community Schools” in the Fall 2015 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

†For more about the research, visit LPI. (back to the article)

‡To read more about each of these findings and the lessons we draw from them, see our full report. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. “What Is a Community School?,” Coalition for Community Schools, accessed April 8, 2017, www.communityschools.org/aboutschools/what_is_a_community_school.aspx.

2. John S. Rogers, Community Schools: Lessons from the Past and Present (Los Angeles: UCLA IDEA, 1998); and David L. Kirp, Kids First: Five Big Ideas for Transforming Children’s Lives and America’s Future (New York: Public Affairs, 2011).

3. Rogers, Community Schools; and Jeanita W. Richardson, The Full-Service Community School Movement: Lessons from the James Adams Community School (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

4. Rogers, Community Schools.

5. Heather Lewis, New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy (New York: Teachers College Press, 2013); Richardson, Full-Service Community School Movement; Mark R. Warren, “Communities and Schools: A New View of Urban Education Reform,” Harvard Educational Review 75, no. 2 (2005): 133–173; and Rogers, Community Schools.

6. Richardson, Full-Service Community School Movement.

7. Rogers, Community Schools.

8. Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill–Brownsville Crisis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002).

9. Derrick A. Bell Jr., “Integration—Is It a No Win Policy for Blacks?,” Civil Rights Digest 5, no. 4 (Spring 1973): 19–20.

10. Podair, Strike That Changed New York.

11. Rogers, Community Schools; and Podair, Strike That Changed New York.

12. Reuben Jacobson, Community Schools: A Place-Based Approach to Education and Neighborhood Change (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2016).

13. Rogers, Community Schools; and Kirp, Kids First. Note that while this kind of help is especially beneficial to children from low-income families, who otherwise do without, middle-class families would also benefit from the afterschool and summer activities; what’s more, having a clinic on the premises means that a parent doesn’t have to leave work for his or her child’s doctor’s appointment.

14. “What Is a Community School?,” Coalition for Community Schools.

15. Pedro Noguera, City Schools and the American Dream: Reclaiming the Promise of Public Education (New York: Teachers College Press, 2003); and Mark R. Warren et al., “Beyond the Bake Sale: A Community-Based Relational Approach to Parent Engagement in Schools,” Teachers College Record 111, no. 9 (2009): 2209–2254.

16. Atelia Melaville, Learning Together: The Developing Field of School-Community Initiatives (Flint, MI: Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, 1998), www.communityschools.org/assets/1/assetmanager/melaville_learning_toget….

17. Laura R. Bronstein and Susan E. Mason, School-Linked Services: Promoting Equity for Children, Families, and Communities (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

18. See, for example, David K. Cohen, Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Deborah Loewenberg Ball, “Resources, Instruction, and Research,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 25 (2003): 119–142; John Hattie, Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement (London: Routledge, 2009); Anthony S. Bryk et al., Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); and Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane, Restoring Opportunity: The Crisis of Inequality and the Challenge for American Education (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2014).